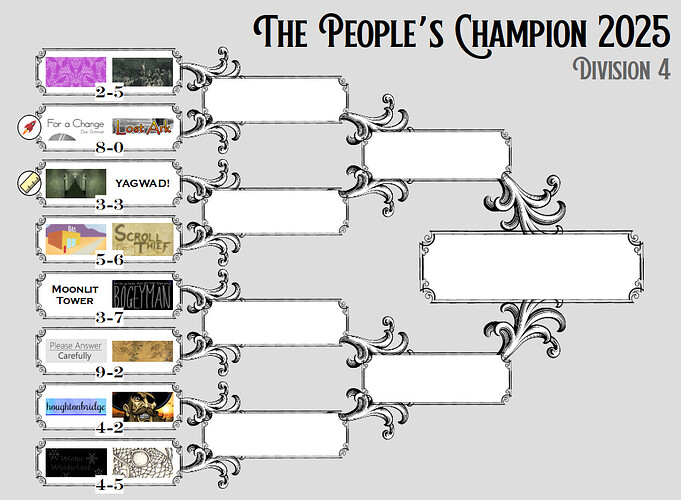

After the first half of Round 2, I decided that there was a fair way to decide what counted as an “upset” victory based on the data from people playing the prediction game. One of those upset victories was Scroll Thief’s win in Round 1 for Division 4. Author Daniel Stelzer was kind enough to answer more than a dozen questions in detail to satisfy fan curiosity. I hope that you find these answers as interesting as I have!

[EDIT: I missed one last answer from Draconis when posting this originally; it’s now added at the end.]

Q: You work with language on a professional basis. What fascinates you about language?

DS: Everything about it, really! There are a lot of things that are amazing about humans, but one of the most important is our ability to communicate. Humans are astoundingly good at communicating—it’s practically impossible to stop humans from developing languages to talk to each other, no matter the circumstances. But at the same time, languages aren’t innate; they’re something we develop as a community and teach generation to generation. And by studying and understanding the mechanics of language (and my specialty in particular, writing systems), we’re even able to communicate across time, reading messages written by humans in the distant past. It’s truly incredible.

Q: Is there anything about linguistics that colors your perception of IF and/or has impacted your authorship of it? If so, what?

DS: Not as much as you might think! There’s some overlap in the mechanics of language parsing; the first real research I helped with, I was in charge of building a model that could parse Lingála sentences into syntax trees, and I’ve toyed with making IF parsers for other languages based on modern syntactic theory.

But really, the biggest impact is that I love games that do interesting things with language and writing.

Q: You’ve said you experimented with Inform 7 as early as middle school. What was it that convinced you to try writing your own first game?

DS: I might be the youngest person now to have gotten into IF via the original Colossal Cave Adventure; I found it on one of those Flash games sites when I was in middle school, and I couldn’t get enough of it. That led me to Infocom, and then to Inform 7; the whole concept fascinated me, and I read both manuals cover to cover.

I made a few early experiments with it, and then saw how badly they crashed and burned as soon as anyone except me tried to play them. That’s when I realized I would need people to actually test the games before release, which led me to the forums and the competitions.

Q: Which of your works are you the most proud of, and why?

DS: That’s a hard one! I try to be proud of everything I release, because otherwise I’d lose motivation to actually finish any projects. But the three I released last year, Miss Gosling’s Last Case, Loose Ends, and Familiar Problems, they all feel like the released product is very close to what I’d aimed for. I don’t look back at them and think “oh, knowing what I know now, I would have done that all differently”, like I do with Scroll Thief or Stormrider. I delivered what I set out to deliver.

Q: You have written some works and co-authored others. How would you compare and contrast the two modes?

DS: In my own estimation, at least, I’m better at planning out structures and puzzles than I am at actually writing the words. So if I can take the lead on the planning and coding while someone else handles the writing, that’s a good deal for me!

But at a more fundamental level, I’ve had different goals with solo authoring versus co-authoring. The solo projects I’ve done, they’re generally because I had an idea and wanted to make it real. The game itself was the goal. The co-authored ones, with Anais or with Ada and Sarah, the goal was to write something with them and enjoy the creative process together. The fact that the end result was a playable game was just a nice bonus.

Q: Were you surprised that Scroll Thief was nominated for the People’s Champion Tournament? What do you think are the things about it that are winning people’s votes?

DS: Very! Scroll Thief was fun, but I also wrote it back in high school. I certainly didn’t expect it to beat a Veeder game in the first round! I’m really touched that people are still enjoying it, over a decade later.

Q: Scroll Thief seems to allow “sequence breaking” in some places – was this intentional design, or is it an emergent side effect of your “desire to generalize all the special cases”? (Or partly both?) Have you been surprised by how people progress through the game?

DS: “Emergent” is a good word for it. One of my big frustrations in the Enchanter trilogy was that the spells were so specific and single-use. You get a spell that brings inanimate objects to life—that sounds awesome! But in practice, there’s exactly one place in the game where it opens a door, and anywhere else it does nothing. It might as well just be a key that opens that one lock.

Scroll Thief arose out of that frustration. Before I even started building the puzzles, I tried to write general-purpose code for each spell. I wanted the magic to be systematic, so that the player would think “how can I combine my tools to solve this problem” instead of “which special-purpose key fits this lock”. That sort of systematicity is what made me really love parser IF in the first place.

But that also means that it’s a lot harder to avoid sequence breaks, like the one in the linked post! I would implement a puzzle like “the key is on the other side of the door, jamming the lock, you have to retrieve it”. Players would find an unexpected way to apply their tools and solve it—use BLORB to put the key in a strongbox, and now it’s no longer in the lock. And I didn’t want to arbitrarily deny this, because that would undercut the systematicity I was going for. When the original Enchanter games did that—adding special cases to block those alternate solutions—it always felt like a cheap trick. So in the end, I left it in, and I think the game is better for it.

Q: The stacks portion of the game is fairly complex but does not seem to have any purpose (unless my playing group missed it). What was the design intent of including it? Was it the abandoned “navigating the hyperplane” puzzle as mentioned here?

DS: Exactly right. I’d originally planned for Scroll Thief to be even more sprawling and epic than it was, but I also wanted the library to stay at the center of it all. I’ve always liked puzzles where you go back to an earlier set piece with new information or new abilities that let you approach it in new ways. So, for example, once you solve all the puzzles in the Colossal Cave area behind the mirror, you’ve learned a spell to see ghosts; now you can go back to the library, talk to the ghosts, and learn about a new secret in the previously-useless junk room.

The Main Stacks were going to be another “return with new knowledge” segment. You’d find a catalog card for some particular book, and locating the book would require understanding the Stacks coordinate system. I actually implemented several different coordinate systems—cylindrical coordinates, spherical coordinates, numbers in base 4, numbers in balanced ternary—and was going to use different ones in easy mode and hard mode. (I think it was base-4 cylindrical coordinates in easy mode and balanced ternary spherical coordinates in hard mode.)

But then the sequels fizzled out. So now the only point of the Stacks is to browse at random and find books with hints in them.

Q: You characterized Scroll Thief as “massively over-ambitious and over-complicated piece” and said that you “spent the next few years unwilling to release anything unless it was up to Scroll Thief’s standards, in terms of size and complexity, which practically meant not releasing anything at all.” In what way(s) is Scroll Thief “over-complicated”? What wisdom would you share with your past self (or new authors) about complexity in design and implementation?

DS: The fundamental problem with Scroll Thief was a lack of planning. When I started working on it, I only had a few points figured out: I wanted to fix the ending of Spellbreaker, I had a neat puzzle idea with the GNUSTO scroll in the display case, and I wanted to make the Enchanter magic system properly systematic. Everything else grew from there as I had a cool new idea, implemented it, and then had to make it work with everything else.

The result was that the game got less and less maintainable over time, because every new piece had to work with everything else, and new pieces were added on a whim based on what caught my interest at the moment. There are still a handful of open bugs on its issue tracker that I never managed to fix.

For all my later games, I tried to scope out the project before I started. ECTOCOMP’s Petite Mort category is a good way to practice this—you need a plan that can be executed in four hours or less, or you won’t finish. Before I started writing Miss Gosling, for example, I’d plotted out the general structure: an introduction and parser tutorial, four major regions each containing approximately three puzzles, and a climax once all four were complete. This kept it from getting out of hand the way Scroll Thief did.

It doesn’t have to be a detailed plan, just a broad-strokes outline. But once you have that, every time you get the urge to add something new, you’ll think about how it would interact with everything else on the outline. Then you can decide whether it’s really worth adding a fully-implemented rope that can connect objects between rooms or not.

Q: You have mentioned many times that you had planned a sequel to Scroll Thief and at least once indicated that it was to be the “first of four parts,” but it seems that you have abandoned the idea. Do you think you’ll ever write a sequel? If not (or even if so, should you want to do a little publicity), what can you tell us about your ideas for it?

DS: In Spellbreaker, the last of the original Enchanter games, you go around collecting thirteen magical artifacts called the “Cubes of Foundation”. Each one represents some fundamental element of reality: earth, water, air, fire; dark, light, death, life; “connectivity” (fate?), mind, change, time; and magic. At the climax of the game, you find out that there were actually four more cubes: four sets of four, plus the “magic” cube as the keystone.

So when I wanted to fix everything and give the trilogy a happier ending (undoing the whole theme of the game in the process—but hey, I was in high school at the time), those four other cubes were the obvious way to do it. I named them “chaos”, “order”, “harmony”, and “balance”, and the plan was for each game in the cycle to retrieve one. (Scroll Thief ends when you obtain “balance”.)

The second game in the series was going to be called “Spirals”, and mostly consisted of an elaborate time-travel puzzle along the lines of All Things Devours—except that, like in Sorcerer, you could interact with your past and future selves. The game would start with a set-piece puzzle in an abandoned coal mine, figuring out how to activate a huge piece of machinery. When it activated, the entrance to the mine would collapse behind you, and a fire would start spreading through the mine. You didn’t have enough time to fully escape, but you could find a GOLMAC spell scroll (travel into the past), and use that to jump back to the moment the fire started.

You would eventually need to coordinate four versions of yourself, using the SNAVIG spell (transform into an animal or person you can see) to avoid paradoxes. If a paradox did happen, you would appear back at the moment before you first activated the machine—this was actually why I developed the Autosave extension for Inform.

The third game, I had two parts planned. The first half I remember very little of, except that it was based around mixing potions; I don’t think I got much further than that. The second half was inspired by the translucent rooms of Enchanter and contributed most of the code that eventually became Labyrinthine Library. A monstrous dornbeast was sleeping on the cube; you had to use a stone-shaping spell to build a maze, then awaken the beast from a distance, causing it to start hunting for you. If you’d designed your maze well enough, you could get back to the starting point and grab the cube without the beast ever catching sight of you. This part is actually fully implemented, and I might polish it up and toss it into a comp at some point.

The fourth game was supposed to be a “fixed” ending to Spellbreaker, where the protagonist of Scroll Thief would show up and save the day. (Very Mary-Sue-ish.) The whole reason why Scroll Thief so awkwardly asks your gender at the beginning is so that the Guildmaster (the protagonist of Spellbreaker) could use the same pronouns, while the Adventurer (the protagonist of Colossal Cave Adventure) would use the opposite ones.

Scope creep ended up killing my motivation thoroughly enough that I didn’t release anything for years, so I wouldn’t expect any of these to actually get finished now. The fundamental problem is that the player at the end of Scroll Thief has so many spells that any new thing they interact with needs a very thorough implementation, and that meant I had to write tons of boilerplate every time I wanted to experiment with a new idea. (Why not just reset the player’s spellbook between games, like the Enchanter trilogy did? Stubborn pride, mostly. I wanted to prove that I didn’t need to resort to that trick.)

Q: Scroll Thief was originally introduced as an incomplete game in IntroComp 2014. In retrospect, what do you see as the pros and cons of this approach? Would you consider doing the same for any future game?

DS: IntroComp is the only reason I ever released any IF at all, so I can’t praise it highly enough for that! The combination of a firm deadline, a community that will thoughtfully review and critique all the entries, and the knowledge that it’s supposed to be incomplete and unpolished, was the perfect blend to overcome my usual perfectionism.

The only reason I haven’t submitted more pieces to IntroComp is because it locks them out of IFComp, and IFComp gets more than double the reviews and critical attention of any other event. But I think it’s a fantastic way to practice actually releasing a project, instead of just polishing and polishing it forever. Without it, it’s quite likely I never would have released anything at all.

Q: You’re an expert programmer of Inform, but you’ve recently released games written in Dialog. What do you like best about each system? Are there any other development systems that interest you?

DS: I love Inform’s natural-language syntax, and I’m sure you’ve heard me praise its readability to the moon and back. Being able to skim code as if it were English prose is an incredible asset, so I always try to write code that reads as naturally as possible. Code is read far more than it’s written, and so on and so forth. Features like custom unit notations are just fantastic, and they’re about to get even better, with enumerated kinds of value incorporated into them.

I also really appreciate that Inform lets you drop down to the I6 (now called the “Inter”) level to implement things that aren’t in the standard library. Anything the Z-machine (or Glulx) can do, Inform can do.

At the same time, though, Inform makes a lot of very specific assumptions about its gameplay. The world model is built into it on a very fundamental level, and the parser is older than I am. There’s a lot of cruft in the system that’s just too old and well-established to alter now.

Dialog, on the other hand, has its entire library implemented in pure, high-level Dialog code, all accessible to the player and easily modifiable. I started writing Miss Gosling in Inform, and it was taking me ages to make the “giving commands to a dog” conceit even halfway functional. When I switched to Dialog, it was handled in a day. Plus, Dialog has hyperlink support built in in a way that takes an enormous amount of work with Inform, which can make Dialog games much more playable on tablets and phones.

The drawback is that Dialog is a very high-level language, and there are various things that it simply can’t do because the language doesn’t give you access to them. I’ve started adding the ones I need via changes to the compiler, but it’s a lot more work than a simple assembly inclusion in Inform. And there are some high-level abstractions (like dynamic relations) that just don’t work in Dialog’s model, while Inform has them built in.

As for other languages, I haven’t really felt drawn to other IF languages beyond Inform and Dialog for parser things, and Ink for choice-based projects. I use various other general-purpose languages in my day-to-day life, but learning a new language is a lot of work, and I haven’t really seen things in TADS or Adventuron or ChoiceScript or such that make me go “wow! I want to do that” enough to learn a whole new language for.

Q: What do you see as the next steps in the evolution of development tools for interactive fiction? Which of those would you most like to see happen, and why?

DS: Honestly, since I7 has gone open-source and the community has taken over Dialog, I haven’t really had much of a wishlist for IF development tools. I wish Inform releases were a bit more frequent, but it feels like most of the development ecosystem is in a stable place right now—which means I have no idea what the next exciting shakeup will be!

Q: You’ve written a large number of extensions for Inform. Which ones are you most proud of? Which ones would you like to see get more use?

DS: Now there’s a tough question! An embarrassing number of my extensions in the early days came from trying to share code between Scroll Thief and its sequels. Nowadays, they’re more likely to come from an interesting coding problem on the forums. But there are a handful that I think are very generally useful, and I hope more people come across them:

All four of these augment one of Inform’s core strengths in a way that I think a lot of projects could benefit from.

Q: Which authors of interactive and/or static fiction are your favorite? Which have most influenced your own style and craft, and in what ways?

DS: I read a lot of genre fiction—science fiction and fantasy, and murder mysteries, are particular favorites. Agatha Christie is always my go-to when I need to de-stress after a big project, which probably doesn’t come as a surprise at this point!

But in terms of my IF style, I’ve always had a particular liking for fiction that plays by its own rules: that lays out a setting, and the rules of that setting, and then the story follows from those rules. The “fair play” murder mystery is a great example of this; the reader has access to all the same information as the detective, and that makes it so much more satisfying when the solution is revealed. Not because you’ve solved it yourself, necessarily—usually I haven’t!—but because you see how someone could have. I think the best example of this I’ve ever seen is John Dickson Carr’s The Three Coffins/The Hollow Man.

But there’s also a certain style of speculative fiction that’s built around a similar internal logic. “Here’s how the setting works; now watch as the plot follows from that.” A lot of Brandon Sanderson’s fantasy is somewhere in that vein; same for some of Larry Niven and Isaac Asimov’s sci-fi, to the point that both of those two successfully combined sci-fi with a fair-play mystery, which is an impressive feat! A scientist invented a device that makes time run faster in a small radius around it; he was found dead in a locked room. How could this have happened? (Niven’s ARM.)

I tend to have that principle in mind when I’m working on IF. I want to build a setting that’s consistent in such a way that you see the puzzle solution and go “oh, of course, that’s not only sensible, it’s the only possible way this could have worked”. All the puzzles in Miss Gosling, for example, started with “what can dogs do, and what can they not do, and how might these turn into obstacles?”