As I read over feedback from my entry in this year’s IF Comp, I was struck by the disparity of “difficulty” reported by players. Of course, challenge is subjective and every player will rank puzzles according to their own experience and tastes, but it feels like there should be a some mechanism to more appropriately quantify difficulty. I’d like to say, with confidence: “This puzzle ranks 5/10 on the difficulty scale” or something to that effect.

Note that I’m not talking about puzzle “fairness”. Although it makes sense that puzzles leaning toward the “Cruel” side of Zarf’s spectrum would be inherently more difficult, I don’t think the reverse is true: A challenging puzzle may also be fair. I see these as different, related things.

So, I have a general concept around estimating difficulty which I’d like to make real: quantifying the difficulty of each granule step required to complete a puzzle, according to a set of rules, summing these values up into a “puzzle difficulty” aggregate, and perhaps even a “game difficultly” measurement. It builds on the foundation of the Puzzle Dependency Map (or “graph”, or “chart”, depending on your preference).

A little bit about Puzzle Dependency Maps (click here)

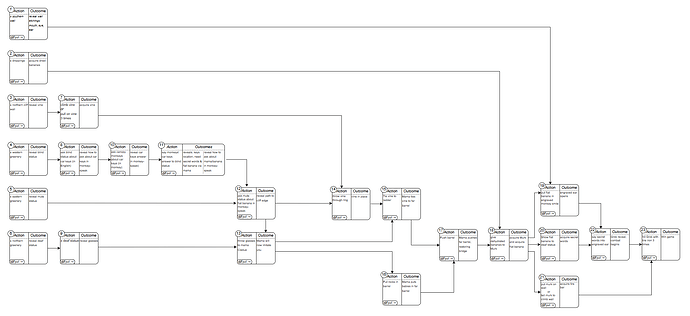

There’s already some online discussion about mapping puzzle dependencies. This practice offers a lot of benefit to the game design discipline (even these forums have this relatively recent thread on the topic) so I won’t deep dive on the topic here. For discussion purposes, the following is one I produced for MaCK:

Some quick notes about my personal approach to these:

-

My tastes lean left to right, rather than top down, because that’s how I read the page and how I transcribe by ideas. It doesn’t align with the pattern of scrolling a window, but… that’s my approach.

-

I also like to include the outcomes for each action. It helps remind me what the action actually does to advance the game.

-

My dependency maps are not walkthroughs; they don’t include every command the player must type to complete a goal. For example, picking up something which was just revealed is assumed.

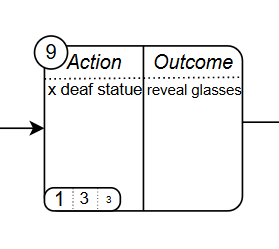

The things I’m considering adding to my map nodes are the difficulty boxes at the bottom left (the upper left circle, “9” in this case, is the step number and can be safely ignored for this discussion):

These are, from left to right:

- The “difficulty” of the given, discrete action.

- The aggregate difficulty of all prior steps which are considered part of the given puzzle.

- The aggregate difficulty of all prior steps since the start of the game.

The end goal would be to apply some interpretation against the aggregated points at any given node in the game chain to determine difficulty.

Which brings me to the actual point of this post, where I’d really like to poll for ideas: How do we objectively measure difficulty of a given step for an average human?

Here are some initial thoughts on quantifying the difficulty of a specific type of action, “Discovery by examination”:

To reveal the object, something else must be examined which is…

-

Clearly Called Out (CCO): Requires examination of something clearly highlighted in the text, usually as a separate paragraph. (+1 difficulty pts)

note: I did consider quantifying CCO at 0pts, but feel like a non-zero value makes more sense when quantifying chains of actions. -

Hidden In Plain Site (HIPS): Requires examination of something mentioned inline, with the description, or minimally obscured. (+2)

-

Obscured In Plain Site (OIPS): Is described in a way which is significantly misleading or obscured. Typically reflecting that the PC didn’t recognize what it was at first glance and the player must see deeper than the character. (+3)

-

In cases where nested examination is required, each scenario would be summed together.

Here’s a set of scenarios to test this initial chart against. The player’s goal in the following is to “discover the red gem”.

Examples of the above rules applied... (click to expand)

| Transcript | Commentary |

|---|---|

| 1. “The sun shines through a little window, illuminating a clean breakfast nook. Four chairs are clustered around the small table. A clock ticks on the wall. On the table is a red gem.” |

The gem is clearly called out separately from the room description (CCO, 1pt). It’s obviously a thing to focus on. Not much of a puzzle at all. Total difficulty: 1 pt |

| 2. “The sun shines through a little window, illuminating a clean breakfast nook. Four chairs are clustered around the small table supporting a red gem. A clock ticks on the wall.” | The gem’s presence is embedded in the room description, so the player will need to pick it out from the rest of the room description (HIPS, 2pts). Total difficulty: 2 pts |

| 3. “The sun shines through a little window, illuminating a clean breakfast nook. Four chairs are clustered around the small table. A clock ticks on the wall. On the table is a cube. > x cube The cube is adorned with a round, red gem.” |

The cube is clearly called out separately from the room description (CCO, 1pt), examining it reveals the gem (CCO, 1pt). Total difficulty: 2 pts |

| 4. “The sun shines through a little window, illuminating a clean breakfast nook. Four chairs are clustered around the small table with a cube on it. A clock ticks on the wall. > x cube The cube is adorned with a round, red gem.” |

The cube’s presence is embedded in the room description, so the player will need to pick it out from the rest of the room description before examining it (HIPS, 2pts) to reveal the gem (CCO, 1pt). Total difficulty: 3 pts |

| 5. “The sun shines through a little window, illuminating a clean breakfast nook. Four chairs are clustered around the small table. A clock ticks on the wall. > x table There’s a cube sitting on it. >x cube The cube is adorned with a round, red gem.” |

Here, the cube is not initially described at all. The table is embedded in the room description (HIPS, 2pts); but after examining that, the cube is clearly called out (CCO, 1pt), and after examining that, so is the gem (CCO, 1pt). Total difficulty: 4 pts |

| 6. “The sun shines through a little window, illuminating a clean breakfast nook. Four chairs are clustered around the small table. A clock ticks on the wall. > x table There’s a cube sitting on it. >x cube The cube is ornately painted with shades of earth, and decorated with precious stones.” |

Similar to the previous: table described inline (HIPS, 2pts); the cube directly described on examination (CCO, 1pt); but, the gem is described within the cube’s description, in a way that is nominally obscured as decorative stones (HIPS, 2pts). Total difficulty: 5 pts |

| 7. "The sun shines through a little window, illuminating a clean breakfast nook. Four chairs are clustered around the small table. A clock ticks on the wall. > x table There’s a cube sitting on it. >x cube It’s dirty, formed of earthy clay; misshapen and covered in lumps. >x lumps As you examine them, you find one of the lumps isn’t part of the cube at all. It’s covered in dirt, but you brush that away revealing a round, red gem. " |

Again: the table is described inline (HIPS, 2pts) and the cube is directly described (CCO, 1pt). Now though, the cube’s description is misleading. It’s not “gem adjacent” or at all obvious that examining lumps would reveal a gem. (OIPS: 3dif). Total difficulty: 6 pts |

So I am curious:

-

What are your thoughts on this approach in general, the above attempt to quantify difficulty for this type of action, and other types of actions.

-

Has anyone applied similar thinking to assessing difficulty, and is there a methodology published some place which I’ve missed?

-

Finally, there may be some thought to quantifying a “negative difficulty” for certain types of mitigation strategies, such as hinting.

I know that all of the above is a can of worms, but I am interested in hearing from the group.

Thanks!

Jim