I told @DeusIrae I’d start this thread, and it really is an interesting topic I’d love to hear from people about, so before I go and get distracted by other unfinished reviews/review-a-thons (do I have the time?!)/Slay The Spire(oh no!):

Empathy mechanics. I talked about them in my review of Dysfluent from IFComp 2023. The empathy mechanic in Dysfluent is timed text: your character has a speech impediment and you often have to wait for text to appear, generally dialogue. This mimics the lack of control over speech the protagonist has. In my review, I wrote this:

(Also for completeness, here’s the Dysfluent post-mortem thread: Dysfluent: a late postmortem for a patience-testing game for the author’s own thoughts on their entry)

Some reviewers complained about the timed text in Dysfluent. Some found it effective. Many pointed out where it could be used less.

The whole idea with empathy mechanics is an attempt to continue to bridge the whole interactive/narrative thing (also known as the crossword/narrative war). “How can games better tell its stories?”

As someone who likes IF because it allows authors to do smaller-scale experiments with things like this, I like seeing empathy mechanic pieces. And in practice, I think I can point to a couple different examples in IF:

Examples

Tedium/Repetition

With Those We Love Alive. Wander the city all you want, you’re trapped, go back to sleep. Howling Dogs. A recurring cage. Cannery Vale. Working in a factory, on an assembly line.

Frustrating/Confusing Environments

Will Not Let Me Go, maybe Shade have sequences that are intentionally disorienting and confusing. Although both are relatively short.

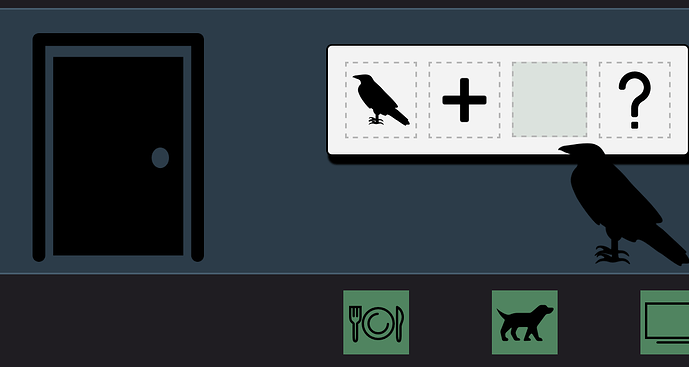

Lack of agency

Rameses. Your character refuses to do or say anything, with lots of self-justification. Depression Quest. Your character is unable to muster up the energy to do certain things, helpful things. The Archivist and the Revolution. Your character suffers from fatigue and can sometimes only sleep, even as work and rent deadlines keep ticking away.

That’s off the top of my head. Plenty of others. Do people have other pertinent examples they can think of?

One thing I’ll note as well: the reception of all the earlier examples were more mixed upon release, with a few huge proponents, and the later examples here (Will Not Let me Go, The Archivist and the Revolution) are more universally positive.

To slightly expand on some of the questions I thought were worth discussing:

Are these mechanics actually successful at communicating something more? It’s still a novel experimental space, but are they effective in practice? How could they be more effective moving forward? What have you found effective, looking back?

There’s the immersion question. If the player experiences a mechanic meant to evoke the same emotion as the one the character is facing, isn’t that sort of like empathy, and thus are you better engaged/understanding/immersed by the story?

But maybe not, and immersion doesn’t actually work that way. Maybe the moment players get inconvenienced, annoyed, or bored, they’re all too aware that this was caused by design decisions made by the game author, and they won’t be able to (or even want to) ascribe those feelings to the story or characters. How large is that subset of reactions?

My other thought is, maybe you don’t actually have to walk in someone else’s shoes all that much, you need just enough understanding to imagine what it’s like. Like I said above: where’s the line between understanding what the mechanic wants to communicate, and how much does the player need to continue to experience it after they’ve gotten the point?

Thoughts? Experiences, with any of the examples, other games, or with your own work?