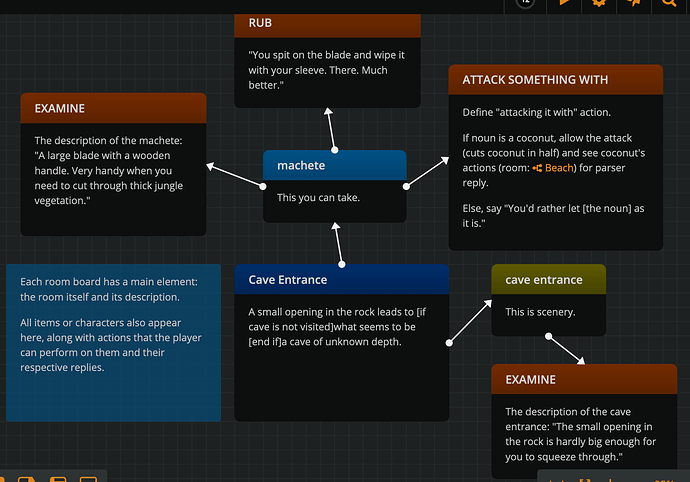

When I open Vizon in my browser, the window is split into two panes. There’s the “puzzle chart” in the right-hand pane, and the code which generates it in the left-hand pane. I simply started messing around with the code to see how it changed the puzzle chart. I added a new action with no preconditions, and then cut and pasted in new actions dependent on that, experimenting with OR gates etc. as I went. My pc is a bit slow, so I turned off the auto-redraw.

The thing I like about it is that order of the bits of code in the left-hand window doesn’t matter: it’s the dependencies which Vizon uses to draw the chart. So I can focus on designing one bit of the game, while the app keeps an eye on the whole game so that if I accidentally short-circuit another puzzle, it lets me know.

If you save the page, it saves the puzzle chart too, somewhere in the bowels of Firefox, but I’m cautious about that sort of thing, so I copied and pasted the left-hand pane into a plain text file and saved that in my project folder. I tested pasting the text into the left-hand pane, and it worked fine.

Vizon doesn’t export to any IF system, so it’s really only useful for generating a chart of what you intend your code to do. So for me the process resolved into:

- Use Vizon to plan the intent of my game

- Code up part of the game

- Use one of the game analysing apps to discover that my code didn’t actually do what I intended!

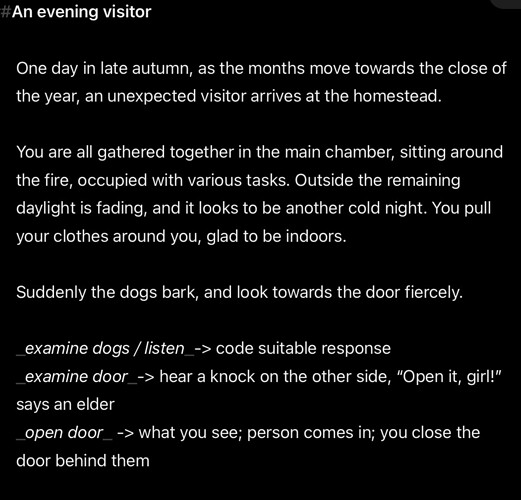

I find that for planning scenes, a plain text editor is best. I sit down and write a fake transcript (with prompts etc.) that represents an ideal “minimal path” route through the scene. If the scene is a “branching scene” – i.e. one where the player can get a good or a bad ending, or it sets the channel for the next part of the story then I write separate fake transcripts for each route.

I find that anything which requires more logic (such as an app that would require me to click in different boxes) defeats the object of writing the transcript because it interrupts the writing flow, and any creative writing (e.g. descriptions and dialogue) turns to cardboard. I think coding and “writing” use different and incompatible parts of our brains. Certainly if I try to do both simultaneously I find I do neither well.

Of course, the downside of doing it this way is that often an expression or process that produces natural prose, or an action that should produce a particular effect, turns out to be an absolute PITA to code. But I think this is the right way to proceed. We should be forcing the machine to do what we want, rather than shaping our stories to fit its cramped capabilities.

Mind you, I’ve yet to out-stubborn the compiler!

It’s only once I have a working skeleton of a scene up that I start thinking about the additional commands and responses needed (a.k.a. a thousand reasons for telling the player “no”!)

That’s part of the reason I’ve become very interested in Dialog recently. I like the way that I can put myself in the player’s shoes and use the interactive debugger to expand the play options in an organic way. Most of the computer theory about why Dialog does what it does the way it does goes right over my head, but I do like the way that it seems to keep the “book keeping” aspect of maintaining the world model separate from the generation of output. This seems to me natural as well as convenient. I’m finding the Dialog engine much less of a buttinsky than Inform 7.