Here a couple I can think of, including stuff you guys have said:

Word Count:

This is a very easy measure for games, and is the main selling point of Choice of Games games (longer games get charged more for and are more popular).

For choice-based games, this usually directly correlates to longer games, but not necessarily for parser games. Pogoman GO! has over 100K in words (which is really unusual), but a lot of that is based on special responses to standard verbs and randomized text, and the whole game can be completed in a few hours.

So Pogoman Go is an example of a medium-sized game with tons of text, while an example in the other direction might be Plotkin’s Praser 5. I don’t know the exact wordcount on it, but I suspect its fairly low, as it just consists of incredibly difficult puzzles, each of which can be solved in a compact fashion.

Another small-code but giant game is Starcross. According to this post, Starcross only has 15K printable words in the code (which if it’s similar to Zarf’s estimates, would be around 45K word of codes), and Starcross is one of the Infocom games I consider really big.

Time to complete

You mentioned this one, and I agree. Time to complete can make a game really feel big, but not always.

SNOSAE is a game that takes a very long time to complete. It’s in DOSBox, and it’s just one series of very hard puzzles after another with little hinting or cluing. If someone had a perfect walkthrough, it would be fairly short.

On the other hand, a game can feel smaller than its time to complete suggests. The House at the End of Rosewood Street takes a lot of actions to complete, but most of them are completely repetitive (delivering mail to 8 different houses on a street for 7 days in a row). So it’s a 2-3 hour game that feels smaller.

A more positive example is Choice of Robots, one of my favorite choicescript games. While it is in fact very large (300K words) it feels even larger because its immensely replayable and has a lot to find in replays. Like, one playthrough is about saving your parents with cancer-curing doctor robots and another is curbstomping Alaska with giant death mechs.

Number of distinct rooms/scenes/interactions

I think this is probably the major indicator of size for me. But there are for sure counterexamples here, like that game Snowball with 7000 identical locations.

Even among games with different locations, it can feel like not that much content. One example is The Northnorth Passage, which has very lush and descriptive scenes in a variety of rooms but is completely trivial to solve. Another similar examples is Toby’s Nose, which has very dense room descriptions and a variety of locations but is relatively brief due to the constrained actions.

Why not all three?

The games that have all three (tons of text, takes a while to complete, distinct locations) are the ones I consider truly large. The problem is many of them just become a blur of memory and it’s very hard to know their actual size in comparison to each other. Here are some:

-

Finding Martin. I suspect this is the largest parser game I have ever played. It includes stuff like a zoo with penguins, time travel repeated multiple times, a phone booth that teleports you around, flavor-based magic, etc. Very difficult, high wordcount, etc.

-

Cragne Manor, which with 80 authors its size shouldn’t really be a surprise.

-

Inside Woman. Andy Phillips is known for giant games filled with catsuit-wearing female assassins and this is probably his biggest game, where you have to fight your way through an immense skyscraper with different levels (like the Shinra tower in FFVII) and uncover its dark history while fighting some symbolic number of female assassins (12? 7?).

-

The Mulldoon Legacy is one of Jon Ingold’s early games, and has a lot of portal-based time travel, lots of unusual mazes, many codes, etc.

-

Blue Lacuna is bigger in code size and locations than many of the above, but is purposely designed to have easier puzzles, so will be shorter than others when not using a walkthrough and vaguely similar when using a walkthrough.

-

Worlds Apart is more story-focused and I swear it’s somewhat incomplete (like maybe the author teased a sequel or more content? Haven’t played it in years despite how much I liked it), but this is very expansive. Very Anne Mcaffrey-esque, which a protagonist singing and communicating with dolphins.

-

Lydia’s Heart is Jim Aikin’s biggest game (I think? I haven’t finished Prom Dress). A very large horror game set in the swamps of the American south. Not Just An Ordinary Ballerina was one of the very first games I played when I discovered IF in 2010, and that was huge; this game is even bigger.

I didn’t include Hadean Lands and Counterfeit Monkey because in a weird way, despite both being monstrously large, they go out of their way to feel smaller by providing many conveniences. Hadean Lands would be far larger without Plotkin’s handy shortcuts, and Counterfeit Monkey is designed to be completed. So I think they provide the same kind of content as the bigger games, but in a more player-friendly and time-friendly way. It’s like all the good stuff, without any of the filler.

Curses is big, and it’s my number one favorite game, but I don’t think it cracks the above list.

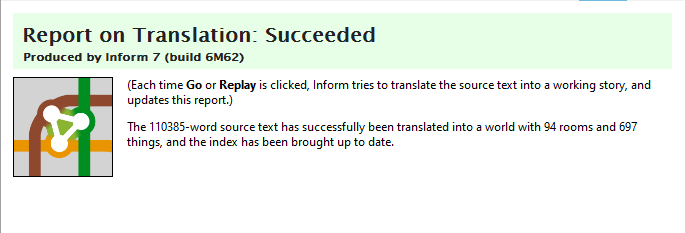

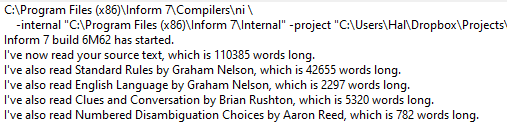

You linked a post of mine above; I’m trying to create a truly large game. I have a list of Games I’ve reviewed that are over 10 hours long, and there aren’t a ton of games on the list, so I want to add my own. I’m shooting for high wordcount, lots of variation and puzzles, and long play time, which is why I set the arbitrary goals of 10 small dimensions, each with about 2 hours of gameplay, so that the final result will be 20 hours (that way even if someone’s way faster than me, it’ll still be around 10 hours to finish).

I’ve beta tested a game by an author that easily rivals the games above, so something like that may be coming out in the future, but that’s up to the author if they want to talk about it.