I thought about this a lot when making my WIP Never Gives Up Her Dead. It has 10 main areas and I wanted each of them to be different. So here are some ways to brainstorm puzzles, each themed around one of my areas.

- You can use ‘traditional’ parser puzzles

I made a haunted house using tradition parser puzzles. These are puzzles that use standard verbs like TAKE, DROP, UNLOCK, GIVE, etc. This basic style of gameplay means that you find something in one area, identify where it belongs, and carry it there, using some obvious verb.

Classic examples include finding a key somewhere and bringing it back, or finding a weapon you use to kill an enemy. Many people that get into parser games do so because they find this sort of ‘medium-sized dry goods’ gameplay enjoyable the same way a wordsearch or crossword is fun.

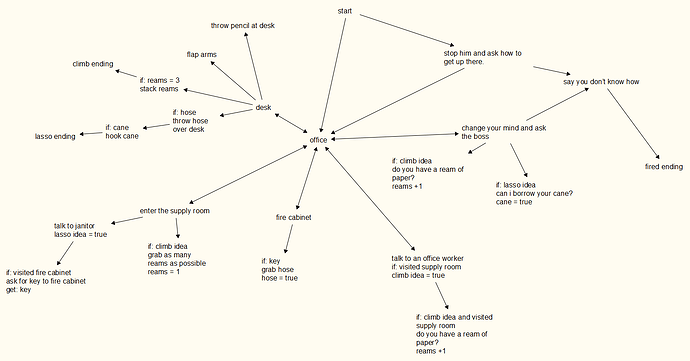

So in this case, I just created many obstacles, and then created solutions to those obstacles, drawing a map first. That’s one way to brainstorm.

- You can theme puzzles around mechanics

My second area, I wanted to have a murder mystery with two mechanics: first, you gather clues and link them to get new clues. Second, you can ‘flash back’ into someone else’s experience, changing the writing and tense.

So to brainstorm these puzzles, I had to think, ‘what kind of interesting situations would arise with these mechanics? What kind of clues could be connected, and how will players know?’

- You can use puzzles from the real world.

My third area is a wax museum escape room. So, what I mostly did here was research what kind of puzzles actual escape rooms use, and think about how to adapt those to IF.

While not from ‘real life’, puzzles from TTRPGs or video games can also be adapted.

- You can brainstorm puzzles based on an overarching set of themes.

My 4th area was a horror area inspired by the Magnus Archives, which classifies fears into 13 or so categories. I wanted to create one puzzle that would be related to each fear; so, for instance, to evoke the fear of claustrophobia, I had a puzzle navigating a tight crack; to evoke fear of fire, I had a puzzle where you had to set yourself on fire.

Giving yourself thematic constraints like this can make brainstorming easier. For instance, having puzzles based on the stages of depression, or Chinese zodiac, or the four humors.

- You can base puzzles on interactions with NPCs.

My fifth area was a robot lasertag arena. The whole idea is that you have to command two robots in battle against a bunch of other robots. This involves communicating with your allies, learning about the enemies and their strengths and weaknesses.

Basing puzzles around interactions with NPCs is often easier since our daily lives contain frequent interactions with other humans that amount to a puzzle (TAKE RECEIPT, GRAB PIZZA, EXPLAIN TO COP WHY YOU’RE SPEEDING, etc.). On the other hand, because we interact with people so much, a game with an NPC that’s not implemented well can really stink.

- You can do ‘tasks’ instead of puzzles.

Complicated tasks that are not puzzles at all in real life can become satisfying puzzles in a game.

I made a cabin in the woods where all you do is restore it. You have to make paint, cut wood to repair stairs, etc. Technically none of it is really a puzzle, but trying to figure out how the author wanted you to do it and then doing it can be a puzzle. I had to include instructions.

Examples of this in other games include microwaving cold food in The Lurking Horror and rowing the boat in The King of Shreds and Patches, or, famously, in Anchorhead, closing the front door.

- You can have movement-based puzzles

Arthur DiBianca does this a lot. Into the Facility is nothing but movement puzzles.

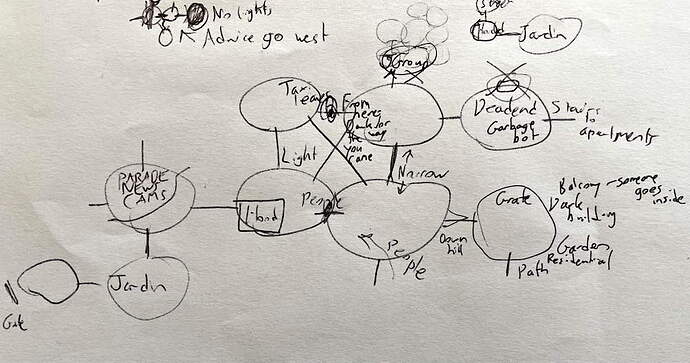

I made a zoo area with a bunch of different animals. The solution to (almost) every puzzle was to get an animal to walk to another area and interact with the others.

With this type of brainstorming, you can just think of a dense area (a city, a zoo, sewers), put a bunch of stuff in it, and imagine what traversing the area would be like.

- You can base puzzles on the capabilities of the system you’re using.

When reading the Inform 7 manuals this 7, I discovered that they included the ability to calculate the inverse hyperbolic tangent. I decided to make a puzzle centered on using that number in the game (by providing an in-game calculator).

I made an area full of floating monuments and based other puzzles in this area on Inform examples and capabilities, including having fire spread in a natural way, modelling hot and cold, performing numerical calculations to model the spread of a gas, modeling currency and a cash and change system, etc.

Edit: If I were to do a TADS game, I’d probably try out some of its sensory capabilities (smell, sound, etc.) because from what I’ve seen they’re really well developed.

- You can use limited parsers or single-room settings

Both of these options can make a parser puzzle more similar to a twine puzzle. So you can borrow a lot of ideas from twine for this.

I made an area with a tool that you can upgrade and various puzzles that were essentially like quizzes. But I found it incredibly difficult, as limited commands and limited map ruled out most of the puzzles I was familiar with.

- You can eschew puzzles all together and just provide an ‘experience’.

This is like Charm Cochran’s recent Gestures Towards Divinity. There is no puzzle, or even a linear flow; there’s just an exhibit you explore.

Galatea is kind of like that too. In fact, there’s a long tradition of puzzleless exploration, including The Fire Tower by Jacqueline Ashwell, current IFComp leader.

Anyway, thanks for indulging me, I’ve been thinking about this a lot over the last year and a half! I probably should have brainstormed more; for instance, I have 54 buttons in my game, just because they provide easy puzzles.

Edit: Also, mazes do suck. They’re the ‘timed text’ of the parser world. Can you make timed text work? Yes, if used in moderation, and if it fits the game. Same thing with mazes; they can work, but only if used in moderation, and only if it makes sense with the rest of gameplay.