Institutional Playthrough of Bee, Part One

I’m grateful for everyone’s comments and suggestions. Next up the institutional playthrough, in which church and school are prioritized. This was a mixed experience. Bee was clearly not made to accomodate such specialized playthroughs, so there are many repeated answers during religious activites. I think this shortcoming could be handwaved away as a reflection of the structured ritual of Episcopal service, but don’t find that explanation sufficient. After all, we are interested in Alex’s responses to life and the world, and repeated insights or reflections make the experience feel mechanical, short-circuiting the empathic bridge that otherwise defines our experiences with Bee.

However, and this is a capital-H However, the passages regarding Pentecost are the most poetic and affecting in the entire game. It is for this reason hard to begrudge the shortcomings of a religion playthrough too much.

Disclosure: I grew up Episcopalian, so the rituals and liturgical elements mentioned in Bee aren’t exotic to me. If you’ve played Repeat the Ending, you know that D refers to himself as a “lapsed Episcopalian and crypto-Catholic.”

Passage from *Repeat the Ending* (SPOILERS)

Hospital Parking Lot

This is the hospital’s large parking lot. Since it is on a gentle slope, it appears to reach beyond the horizon, lost to the curve of the earth. We stand near a white stone statue of Saint Catherine of Siena. Even though we are too far away to read its inscription in the dusk, I know that it must read, “LOVE FOLLOWS KNOWLEDGE.” Well, we both know that isn’t true, but it’s more beautiful than the average lie.

I acquired this knowledge as a lapsed Episcopalian and crypto-Catholic. Not in the sense of Catholic theology, mind you, with all of its shabby Aristotelianism, but of its lovely pageantry and mythology. I also know, for instance, that after Catherine’s death, pious grave robbers stole her head. Today, visitors and pilgrims can view it in an elaborate reliquary inside the Basilica San Domenico in her hometown of Siena.

This statue features her whole body, head and all. Looking forward with a serene expression, she holds a book in one hand and a lily in the other. What would it be like, I wonder, to believe in magic? I don’t mean in the sense of things that we can do. I mean the opposite of that. What if we lived in a world where everything meant more than we thought it did instead of less? A world absolutely besotted with significance? If power were additive rather than subtractive?

There’s something about this light that settles me. I feel as if I could stand here forever. You know, until we go in and up, our mother is in a quantum state. She could be going downhill fast. She could be laughing at sitcoms and eating a cheeseburger! I have the sudden feeling that we live in a very open world, that our world is wide open. You must feel it, too. Surely you feel it.

Behind us, someplace under a tree in the gathering dusk, is our trusty Accord sedan. Above and before us hang the countless lit and unlit windows of the hospital. I have come to throw my shadow against one of them, haven’t I? I guess we can’t stay here forever, but don’t you agree that there is something about the light? I can’t say what it is. I don’t know.

Ha. You’re right. It’s very unusual for you to tell me to hurry up. I must be nervous! How funny. I guess there’s nothing for us to do but walk past St. Catherine of Siena, Doctor of the Church, and try to talk our way upstairs even though visiting hours are over. I should hurry in. The reception desk should be just *INSIDE*.

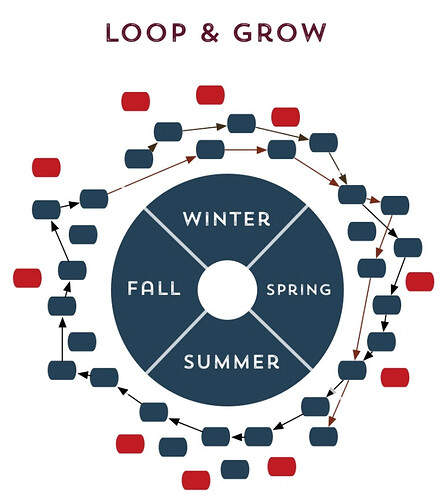

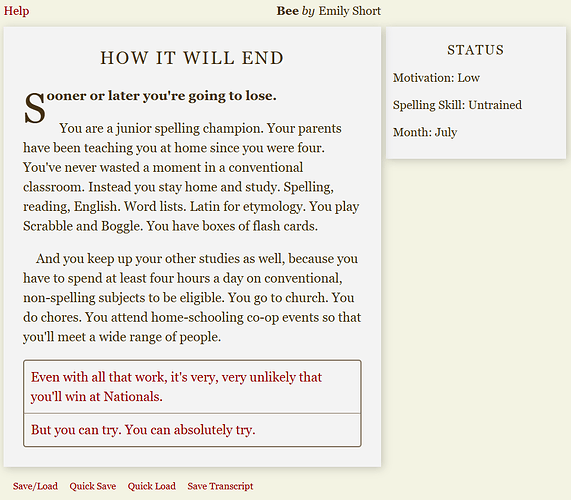

As the game begins, we click through three choices. We aren’t choosing outcomes, mind you, because in the end we must click each one, but we are perhaps stating our priorities.

Contents

------------

- Lettice

Your sister’s place.

- Church

Where you spend most of the time when you’re not at home.

- The Co-op

Shared resources with other home-schooling families.

This choice suggests that the protagonist’s world is a triangulation among these poles. That isn’t true, we learn, but it gives us a starting point. I choose the church first, since that is our priority.

Church

--------

You go to church at least once a week, obviously, and often more than that during certain seasons. There is special Bible study during Lent, and a lot of services around Christmas. Besides home and the Co-op, church is the place you know best in the world.

- Your favorite thing is the flowers and stained glass.

- What’s more, it’s very familiar.

- Still, sometimes services get very boring.

> What’s more, it’s very familiar.

There are kneelers you can pull down when it’s time to pray. There’s a red prayer book and a blue hymnal and a brown Bible in a rack on the back of the pew in front of you. There are white donation cards to go with your offering, and pink comment cards, where you can leave your phone number if you’d like to be contacted by a member of the Newcomers’ Committee. There are short, pointed pencils, but they were not put there for children to draw with, which is why you may not use them to make stick figures in your service leaflet.

All these things are as familiar as your own house, as inevitable as dinner forks in the kitchen or washcloths in the shower.

- Some people don’t know when to use the kneeler and when to stand.

> Some people don’t know when to use the kneeler and when to stand.

Some people don’t know when to use the kneeler and when to stand, which must be embarrassing for them. But you’ve been here forever. You can do church on instinct. You don’t need the bulletin insert to know the tune for the Sanctus; you don’t need to read the Nicene Creed out of the prayer book.

At worst, the words are just under the surface and you have to grope around a moment, like searching for a shampoo bottle dropped in the bath.

For those unfamiliar with Episcopal liturgy, it is very similar to service in the Catholic church, featuring a set structure and many repeated elements. Other elements vary based on the church calendar, and some of these events are featured in Bee. I find it meaningful that Alex sees the church in terms of rules, prohibitions, and repetitions. This is a world of familiarities. Whether they are constructive or numbingly rote remains to be said.

I love the characterization of imperfectly-remembered ritual as “searching for a shampoo bottle dropped in the bath.”

Since this is an institutional playthrough, we are also interested in school life.

The Co-op

----------------

Your local home-schooling co-op is one of the biggest in the state.

The co-op has its own resource center, a rented storefront in a strip mall surrounded by pine trees. Inside there are shelves of used textbooks, parent guides, and inspirational literature, donated by families who have already been through them.

- Sometimes the books supplement when families are on a low income.

- Or introduce them to new ideas.

- Also, there’s a much bigger dictionary than most families have at home.

> Sometimes the books supplement when families are on a low income.

The battered set of Saxon Math books has been in circulation since possibly the 1990s. “Help me virgen mary” is written several times in pen in the margin of Algebra 1/2. This caused a bit of a ruckus when the book was returned. Mrs. Perry put a warning sticker on the front that said “please note marks on page 34” so that no Protestant parents would be taken by surprise.

People still keep checking them out anyway.

Sometimes one of the parents with special skills will run a class for the whole co-op: how to count in French, for instance, or how to dye yarn.

These classes are held in the back room of the resource center. Inside it always smells like something sweet and brown and sickly, wafting from the home-brewing supply shop next door.

- Mercifully, your parents don’t sign you up often.

- Actually, it might be nice to have more classes with other kids.

> Actually, it might be nice to have more classes with other kids.

Maybe the classes you’ve been to weren’t that challenging, but it’s nice sometimes to know what other students are working on. It’s so hard to tell how you compare with everyone else when you’re just doing home-planned curricula in your own living room.

The Co-op also has a bulletin board, where parents can announce field trips and projects that they’re offering jointly. Your parents typically do not organize these things, but just wait for Mrs. Perry to call and invite you. Mrs. Perry organizes everything.

- Maybe it would be better to be one of the Perry kids.

- Then again, nothing could replace your own parents.

> Maybe it would be better to be one of the Perry kids.

Other parents are always talking about Mrs Perry and the Perry kids. Her picture appears on the front of homeschooling magazines, and she gives interviews about how to raise Godly children.

They’re like an example in a textbook; you overheard Mother saying so to Father once. “A textbook example,” she said, and she looked annoyed. Maybe she was jealous too.

Even though the co-op is “one of the biggest in the state,” we rarely get a sense of its size. Perhaps that is because Alex’s own school experience seems largely isolated and self-directed. In fact, I am not sure that we ever see anyone teach Alex anything, although she does join a field trip to the zoo. My experience is that most school vignettes are largely about the co-op’s de facto leader, Mrs. Perry. Another stated priority of the playthrough was strengthening Alex’s relationship with Mrs. Perry, but I was not able to accomplish that. She is nevertheless a force to be reckoned with, and “her picture appears on the front of homeschooling magazines.” As a homeschooling celebrity, Mrs. Perry is viewed with a combination of admiration, envy, and resentment. I am sure that appreciation is somewhere in the mix, too.

School is an isolated experience for Alex, and she does not have a strong sense of the academic life of her fellow co-op members. In fact, an important feature and theme of Bee is isolation. Having played through Bee twice now, I feel convinced that its central tension is the pull between inwardness and things of the world. In this model, the spelling bee, religion, and church are center interiority. Even if the bee itself is an open, public thing, preparation of the bee is done in near-monastic isolation. The things of the world, on the other hand, are things rooted in human connection: Lettice’s art, Sara’s literature, Jerome’s cinema, the wealth of the strange Barron family. I’m sure we’ll continue to pull at this thread!

An important thing to note in these non-spelling bee playthroughs: there is not enough content to focus on specific outside things. There aren’t enough church and school activities to fill out the calendar. That makes sense; the stated dramatic question of this work is whether or not Alex can win the spelling bee, not whether or not she is ready for Confirmation. To avoid this playthrough bleeding into other ones, Alex studied for the spelling bee when no church or school options were available. Besides, I have a suspicion–untested–that the game might end if Alex can’t win the local and district bees. I’ll confirm that before the next playthrough.

Because it is school-related, this playthrough’s Alex gets involved with the school newsletter, which is put together by her father. This is an activity that repeats with multiple unique responses.

The Homeschooling Newsletter

-------------------------------------------

“Listen to this little tidbit,” says Father. And he reads off a limerick about the apostle Paul and the province of Gaul.

Mother looks at Father over the top of the sewing machine. “Limericks are an unclean form.”

Father looks crushed. “What do you think about double dactyls?”

- Discourage the poetry.

- Leave it to Mother to field this.

> Leave it to Mother to field this.

Mother runs another stretch of cloth under the foot of the sewing machine, and its aggressive chunk-a-chunk-a-chunk makes her answer for her. She is putting a brown calico frill at the bottom of a mud-colored day dress, and now is not a good time to interrupt her.

“I want this newsletter to stand out,” Father explains. “Both for the quality of its content and for its playful appeal.”

- Volunteer to provide some puzzle content.

- Suggest including some drawings by Lettice.

- Say they already have plenty of content.

> Volunteer to provide some puzzle content.

“Perhaps there should be a puzzle or challenge,” you suggest. “It would be useful because parents could use it as part of their weekly learning with their students.”

Father looks at you intently. “You should write this challenge,” he says.

“All right,” you say. It will cost you hours of your Saturday every week to construct the challenge, and you will not be remunerated. Whether it does any good to the reputation of the newsletter, you never know.

Father goes away, tapping his pen against his lower lip. “Five hundred thirty-two subscribers,” he says. “And counting.”

This passage illustrates how funny Bee is! “Limericks are an unclean form,” while hilarious, also illuminates the nature of this family’s conservatism as a literate abashment that would find itself at home in a Nathaniel Hawthorne story.

It is additionally noteworthy to see Alex’s interest in puzzlecraft, given the author’s career trajectory.

One of the rare Mrs. Perry activities involves writing letters to a lawmaker in order to protest a bill related to school bullying. This places Alex in the rather ignoble position of protesting anti-bullying efforts in the state education system. Unlike so many other activities, there is a marked absence of thoughtfulness or reflection. It’s out of character for Alex, I think. What can we take from this?

A Call to Arms

---------------------

Calls from Mrs. Perry come in the middle of the afternoon.

- What can that be?

> What can that be?

Mrs. Perry is a home-schooling activist. She doesn’t just school her own children. She runs classes for the co-op. She speaks at the State Fair and at home-schooling conventions. She has a website and a blog. She reviews textbook materials. She has her children give ratings to everything they read or study, to identify for other home-schoolers how thorough, correct, and Godly those materials are.

Mrs. Perry’s children gave a 3.5 out of 10 possible points to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, entirely for thoroughness. The definition of evolution did not meet with their approval.

This afternoon Mrs. Perry has a task for you and your family, to write to your state representatives to protest a change in the laws about school assessment that would add anti-bullying lessons to the common curriculum, going so far as to specify particular curriculum materials to be used.

Mother gives you and Lettice each a turn at the computer to compose your own letters.

- The curriculum would pose an extra cost on home-schooling students.

- It’s not the job of the state legislature to specify particular curriculum materials.

- Home-schooling students don’t suffer so much from bullying.

- And anyway, attitudinal education is repulsive and un-free.

> It’s not the job of the state legislature to specify particular curriculum materials.

You stare into the blank face of Microsoft Word and then begin to type. Starting from a rough outline, it takes you about two and a half hours to come up with something you’re happy with. When you’re done, Mother prints your letter; you sign it and put it into an envelope she has waiting.

- Mother will be pleased.

- Mrs Perry will be pleased.

> Mrs Perry will be pleased.

“When you see Mrs. Perry, you can tell her how many pages you each wrote,” she says. “I think it would make her very happy.”

“I bet we wrote more pages than the little Perry children,” says Lettice.

“Yes,” says Mother. “I think maybe you did.”

The scene is reminiscent of some of the other “child labor” scenes from Bee (we haven’t discussed these yet). Perhaps Alex does not think deeply about the legislation because the subject matter is rather adult (though that never seems to stop her). Perhaps it is simply a job in which the “pay” is the approval of Mrs. Perry.

A return to the newsletter yields a pleasant encounter with Alex’s father.. Wait! I’m realizing now that I should reserve comments regarding the newsletter until we do the “late stage capitalism” playthrough, since this is another example of labor and its ability to establish value within the family. We’ll return to both letter-writing and newsletter-editing in a future post.

More on-topic is the annual zoo field trip, complete with a wholesome Simon and Garfunkel reference.

It’s All Happening At the Zoo

--------------------------------------

“Well,” says Mother brightly, “you and Lettice will have to manage without me, because I am completely swamped with orders this year.” She’s been selling children’s shirts online to supplement her income, and her sewing desk is covered with brightly colored fabrics. So it’s up to you to carpool with other families and find proper chaperonage.

- Go to the South American exhibit with the Perry family.

- Wander solo and see the polar bears.

> Go to the South American exhibit with the Perry family.

Mrs. Perry is wearing an A-line skirt and pearls, and holds her daughters by the hand. Mr. Perry is not along because he works days at a factory that puts custom upholstery on furniture.

You and Mrs. Perry and Mrs. Perry’s children work your way through the South America exhibit, taking in llama and capybaras and other curiosities. The scenes are arranged from north to south, so that the penguins are reserved for last.

Mrs. Perry stops frequently and hands you the family camera. “Here, could you just get a snap of us here?”

She poses with the two girls. “Honey, point towards that bush as though you’re noticing something behind it… yes, like that. Now you… okay. Do we look too posed? Very good. Snap now!”

- Snap obediently.

- Wait for an awkwardly candid moment.

> Snap obediently.

You press the shutter.

“Thank you, dear,” says Mrs. Perry, retrieving the camera from you. “It’s such a pity that your mother wasn’t able to make time to escort you to the zoo herself.”

There’s a lot going on here, including more class and capital topics that I will defer for now. For the purposes of this playthrough, two things interest me. The first is the manufactured candidness of the photograph, which will likely find its way into an image-bolstering context. The second is the absence of parental supervision. It must be said that, for a child who spends most of her time at home, we seldom see Alexis’s parents. I’ve noted this in terms of her self-directed studies, but I feel the absence is more profound than that. Without our intervention as players, Alex leads a lonely life.

After what feels like a long time, we are finally invited into the religious life of Alex’s family.

Advent

----------

Advent begins with a wreath, and four candles in it. Purple candles for the first two Sundays, a pink candle in honor of the virgin Mary for the third Sunday, a purple candle again for the last Sunday before Christmas. In addition, there is a cradle for the baby Jesus into which Mother puts a straw every time you do a good deed.

- Set out the Nativity pieces.

- Open a door of the Advent calendar.

> Set out the Nativity pieces.

The Nativity set is laid out at the beginning of the month, though the Christ child remains wrapped up in cotton until the night of the 24th.

As for the three wise men and their camel, they start their journey on a bookshelf on the far side of the room from the stable, and are advanced day by day, not to reach their destination until the Feast of the Epiphany on January 6.

So much is set down by tradition. But there are other artistic decisions to make. Does the angel go on the roof of the stable, or down on the ground with the humans? Since no nativity star comes in the set, should this be made of silver or gold paper? Stuck to the wall above the scene or hung from a thread?

Advent is the liturgical season that precedes Christmas. Like the date for Easter, the beginning of Advent varies, but it always ends on Christmas Eve. There’s an interesting tension here between the comfort of familiar ritual and the friction of existential decision making, as in the case of the specific arrangement of parts within the nativity scene. We know there are angels, but where are they? How does one construct and place a Star of Bethlehem in such humble circumstances?

There is no Christmas or Christmas Eve in Bee, so far as I can tell. This notable absence is almost certainly deliberate, though I cannot say what it means. Perhaps Christmas has become so concerned with things of the world that it would be hard to describe within the context of Alex’s world.

The next event is Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent and the day after Mardi Gras. By tradition, Ash Wednesday is the day congregants are called to reflect on their own mortality. Many outside the church will recognize the phrase “Remember you are dust, and to dust you will return.”

Ash Wednesday

------------------------

It is time for the Lenten sermon. The air smells like incense.

The point of the sermon is the same as it always is. We are all sinners. We must find out our worst characteristics, our most serious fallings away, and address these.

After the service, Mother and Father have you sit down and write down your lists of things you wish to correct in yourselves during the Lenten season, to make way for the coming of the savior.

- Be more diligent at spelling practice.

- Give the blandest possible answers. You’re not that bad.

> Be more diligent at spelling practice.

In handwriting smaller and neater than ever, you write down your intentions: to reduplicate your efforts, and win the championship, for the glory of your Maker and the good name of home-schooling children everywhere.

Here, Ash Wednesday is narrowly construed as a time to reflect on personal sins and failings. Alex, who doesn’t understand such things, interprets “failings” literally, promising to work even harder and win the national spelling bee. This naive understanding of Lent suggests an insufficiency in Alex’s religious education, despite her family’s outward displays of religiosity.

Observations of Lent continue. We’re ultimately able to choose each of these options, so we’ll walk through them all.

Lent

-------

Where does one begin?

- The discipline of silence.

- The discipline of Wednesday night Bible study.

- The discipline of moderation in food.

- The discipline of fasting on Fridays. [Unavailable]

You’re too young to fast.

> The discipline of silence.

Your household exercises the discipline of silence during Lent: no word spoken aloud from dinner until bed time. This means also no audio programs on the computer, no games or television, and no read-alouds; just quietness and contemplation.

When Lettice was younger, the Silence bothered her very much. Lettice needs attention.

Recently she has taken to rolling out a sheet of butcher paper on the floor, or taping together smaller sheets of paper to make a display as grand as a screen. She sprawls across it and draws dramatic things. It is getting harder to ignore Lettice’s drawings.

Tonight she’s made an image as though you’re looking down from the edge of a pit. In the pit are monster arms reaching out to grab the unwary.

Mother hops over the pit on the way to the bathroom. She makes a terrified face. Lettice laughs silently.

This is an enjoyable scene. Despite the expected seriousness of the moment, Lettice’s drawing and her mother’s surprisingly playful leap over it are a moment of relief. Alex’s mother is an elusive figure. She disapproves of limericks, yet likes the monster-pit drawing in the midst of somber Lenten observations. Perhaps by the end of our journey, we will have a better sense of who she is.

> The discipline of Wednesday night Bible study.

Every Wednesday night during Lent, there is adult Bible study at church. Most of the other children play in the nursery, if they attend this session at all. The lucky little Barrons stay home with a baby-sitter.

Father insists that you are adult enough to understand the adult Bible study, and therefore you will attend it; though you will sit in the back and not say anything. You are allowed a notepad for recording your thoughts, however, so that you can share these thoughts with Father privately after study.

Mostly you do not have any of the kinds of thoughts that Father would like to discuss with you. Instead you use the notepad for writing down things you observe about the adults. Mr Harrison has a single black curly hair that grows out of the end of his nose. Why doesn’t he pluck it out? Is that what it means to be an hairy man?

Presumably, the class is discussion of the story of Jacob and Esau, with its memorably strange passage “And Jacob said to Rebekah his mother, Behold, Esau my brother is a hairy man, and I am a smooth man.” I can’t place the use of “an”, which strikes me as more Anglican (I’ve made a joke) than American. Then again, the snippet might be a recreated performance of a New England accent, since we are dealing with spoken rather than written word.

Because a precocious girl like Alex would have no trouble understanding this story, I think we can see that Alex enjoys (or finds reassuring) the ritual of the church but not the semantic content of its texts. Or, perhaps, she does not care for the spoken discourse surrounding those texts. I don’t believe that we ever see her interact with a bible directly. In any case, bible study is another instance of Lenten sobriety falling through.

Let’s go back for more bible study.

Try Bible study a second time.

This time Father gives you more specific instructions about the notes you’re to take. “Start by summarizing the discussion,” he says. “When Abraham Lincoln was a boy, he could sit through a two-hour sermon and then come home from church and tell the whole thing verbatim to his mother.”

“His mother didn’t go to church?” you ask.

“Perhaps she was housebound,” Father says. “Anyway, your job will be easier because you can write notes, which Abraham could not.”

- Ask if he means Abraham Lincoln was illiterate at a young age.

- Do your summary without notes too. As a point.

Ask if he means Abraham Lincoln was illiterate at a young age.

“Abraham Lincoln couldn’t write?”

“He didn’t write. He committed the entire sermon to memory as it was spoken,” Father says.

- Privately doubt the accuracy of this anecdote.

- Ask how that could be possible.

Ask how that could be possible.

“How would it be possible for anyone to memorize that much at once?” you ask.

“You memorize your spelling letters,” Father replies.

“True, but…” Hm. It seems different. Your spelling words stay put on their cards until you get them into your head. How much harder would it be if the words were just washing over you in a single stream, too fast to review?

But Mother knows more than Father about ancient rhetoric techniques, and she spends the car ride telling you and Lettice about Memory Palaces and how you could imagine the parts of a speech being associated with things in a house.

Another Lenten observation that is not terribly Lenten. It seems the main manifestations of religious life in Bee do not really involve religion. This is a conversation about notetaking. It would apply to notes regarding the most lascivious and sinful thing one can imagine just as well as it would to a Bible study conversation. What is religion in Bee? Clothing, school, strange financial arrangements. Far be it from me to say that anyone is not “religious enough,” but it’s odd that Bee’s outward displays of religiosity do not seem to indicate religious interiority or seriousness. That might be a rewarding critical trail to follow.

However, there is a tantalizing passage here: the classics background of Alex’s mother (or at least a background in classical rhetoric). I feel that of all the characters in Bee, she is the one I wish that I could know better.

Lent culminates, of course, in Easter.

Easter

----------

The service of Easter vigil is a long one, held late at night and into the next morning. Mother and Father fast beforehand, and perhaps when you are older, you will as well. There are a lot of lessons, read by candle-light, and the best part about the service is that you get a candle of your own to hold while you listen.

- Drill yourself on spelling to keep focused.

- Be still.

- Keep an envious eye on the acolytes.

- Be a bad influence on Lettice, and vice versa.

> Be still.

You are very still inside and out. The candles all around you show just a bit of each parishioner’s face. The familiar characters seem smoothed out and gentle.

Perhaps this is what people will look like in heaven, you think. A little bit glowing, and ageless. Like their nicest selves.

Then: will we all wear Easter hats to heaven?

We’ll have to save being a bad influence on Lettice for another playthrough!

This is a nice passage, in which we see Alex engaging with these adult concepts in a thoughtful and illuminating way: heaven as a home to one’s “nicest” self. The humorous question of Easter hats is a nice addition. What is the theological significance of Easter hats? Neither I nor Alex seem to know.

Pentecost is observed as the day on which the Holy Spirit visited the Apostles, empowering them to do the work of the church. By tradition and scripture, the Holy Sprit is characterized as “tongues of fire.” Fittingly, Alex thinks of fire-related words on this day:

Pentecost

---------------

Pentecost is celebrated in church with bagpipe musicians, and acolytes carrying gold and orange streamers, and people who read the Bible lesson aloud in tongues, which is to say all the languages that they happen to know.

Ms. Chang reads in Mandarin, and Mr. Harrison in German because he did a college year in Germany; and the pastor in Ancient Greek, and Mother in Latin. And you hear words of your own, and think of…

- FLAMBEAUX.

- CRUCIBLE.

- IGNIS FATUUS.

> FLAMBEAUX.

flambeaux, lighted torches

Something ephemeral, leaping, distant and timeless, unlike electric light. That which belongs to marriage torches, to Venetian carnival, to dungeons where martyrs died. The whole broad sweep of human experience that you have so little access to.

Pentecost is the most beautiful and frightening of services because it makes a fire of God, and fire is unpredictable, joyful and destructive.

Perhaps Alex is taken by the spirit herself! The language here is poetic and striking. “Pentecost is the most beautiful and frightening of services because it makes a fire of God,” stunning. The journey from marriage to festival to the death of martyrs in the dark is an astonishing and imaginative leap for this young protagonist. We’ll be able to look at the other choices soon.

I’m getting close to the character limit, I think, so I’ll go ahead and post this. More soon, maybe tomorrow, regarding this institutional playthrough of Bee! You don’t have to wait to comment, of course, chime in any time.