4x4 Archipelago (#44) vs. The Impossible Stairs (#53)

This is one of the shortest matchups of the competition, with both games weighing in at 1-2 hours, although Archipelago has a lot of replay value.

4x4 Archipelago is my personal favorite of agat’s games, and that’s saying a lot, since there are a ton of great games out there (like The Trials of Rosalinda, which I recently played and gave 5 stars to).

4x4 Archipelago is a fantasy Twine game on a map that is a 4x4 grid. Each square is an island with different properties. Some are safe, some are difficult, all are exciting. The main gameplay is a fantasy RPG. You go to an island, look for treasure, fight monsters, accept quests, and trade in goods. The way you interact with the world is completely different on different playthroughs; you can start as different classes, each with a variety of powers and long-term goals. You can become a powerful magic user who shapeshifts into Godlike beings or the richest merchant on the sea, and so on. One of the few IF games that I’ve replayed multiple times for fun.

Impossible Stairs is my game, so I defer describing it, but would be happy for someone else to do it for me (Max, who did it last time, is out of town).

The Mulldoon Legacy (#35) vs. Endless, Nameless (#31)

Two long puzzle games from two powerhouses of IF: Jon Ingold, and Adam Cadre. Each is the longest game that their respective authors wrote (excluding Inkle collabs with other authors).

The Mulldoon Legacy was a kind of white whale for me when I started IF. I had played Curses, which was huge, and then finding that Mulldoon Legacy was quite a bit larger blew my mind. This is one of the largest IF games ever made in terms of puzzle difficulty and overall length, although several games have overtaken it since then. The idea is that, after a brief prologue, you are exploring a closed museum to find your legacy after the passing of your grandfather. But the museum has many secrets to tell.

Players should not expect to complete this in a day, or even a week without hints. A more reasonable goal might be to just explore as much of the museum is available; you can get a lot of the feel for the game from the first available areas.

Endless, Nameless is Adam Cadre’s magnum opus, in some ways; his latest and largest IF game. It represents within itself a mini-history of IF. It starts with a simulated command-line BBS system, then segues into an old-fashioned game. As we play, we begin to see the history of IF unfold. The game changes drastically. There are characters in the game representing either real people in IF or symbolic figures in the IF community, and there are a lot of ‘meta’ shenanigans. Interestingly, the ‘old’ game seems to be modelled after Paul Panks’ game Westfront PC. Panks was notorious for cranking out game after game with the exact same setup (randomized combat with a town with a church on one side and a two-story tavern on the other etc.), and most were very low quality, but Westfront was his biggest one, and this game has a lot of similarities to it. Panks passed away in recent years, but I’m glad that his work had some impact.

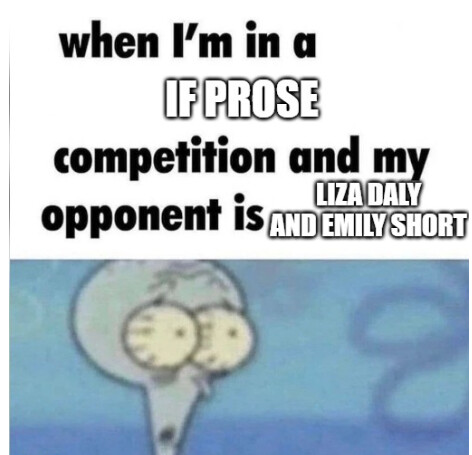

Harmonia (#47) vs. Savoir-Faire (#12)

These are two games by two of IFs best writers and designers. Interestingly, they teamed up in the past to make First Draft of the Revolution, an early choice-based game that inspired the cycling and replace mechanics in twine. Great to see them here together in the playoffs.

Harmonia is a choice-based game by Liza Daly, a longtime IF author, and IFTF board member. It’s written in her custom language, windrift, and features some of the best CSS and styling in any choice-based game.

The game is both academic and personal, trending to other genres later. You are a new hire at a small college and are teaching about Utopias in 19th century literature. You soon find that there is a deep mystery regarding your predecessor, and begin to uncover the secrets of the college.

Gameplay is heavily influenced by written text, with ‘aside’ links resulting in a scribble note in the margin of the game, and pieces of paper you find having a different appearance than the rest of the game.

The story is complex, but this game isn’t too long.

Savoir-Faire was perhaps Emily Short’s pre-eminent puzzle game before Counterfeit Monkey, and remains a very popular game. You play as a kind of wealthy ne’er-do-well who has returned home in disgrace due to a lack of funds. You are hungry, and want some money, and must explore your ancestral home for both food and treasure.

Unfortunately, you are also kind of a snob and will only eat complex home-cooked foods. Fortunately for you, you live in a world of magic! The ‘lavori d’Aracne’ is a magic system that lets you connect any two similar objects together in a way that they share properties. Connect a glass ball to an iron ball, and it won’t break; connect a mirror to another, and you can see through them.

The game has incredible puzzles involving many aspects of physics including density, weight, color, temperature, flammability, and so forth. It does take several hours of gameplay, and the average player will most likely take a week or so playing while writing down notes. However, it is remarkably consistent throughout, and so just a few minutes will give an accurate idea of the play style.

Treasures of a Slaver’s Kingdom (#23) vs. Bronze (#37)

These two games both feature sprawling maps and takes on popular stories in fiction.

Treasures of a Slaver’s Kingdom is a limited parser game from the time that no one was making limited parser games. It’s influenced by Conan the Barbarian, and uses custom verbs like ASSAIL and PARLEY, although the regular verbs work too. The game is an epic RPG quest, where you fight monsters, get treasure, level up (kind of), and so on. It’s a former commercial game, and the creators estimate it to take 6-15 hours to play. It comes packed with goods; like Repeat The Ending, it simulates its own history, and includes a PDF scan of the ‘gamebook it originally was based on’. Has lots of fighting and lots of sexual scenes (though they are of the ‘fade to black’ variety).

Bronze, on the other hand, was originally a Speed-IF but is now one of Emily Short’s largest games. Over the years, Emily Short tried a lot of ways to bring in new players. This game features a big, sprawling castle and a tutorial mode for new players. It features fairly simple puzzles, a well-designed hint system, nudges towards correct verbs, etc. and has served as a good IF introduction to many people.

It’s based on Beauty and the Beast, the fairy-tale version and not the movie. The Beast is no angel in this one, and has a long, dark history. The castle is enchanted, but each enchantment is connected to a musical instrument. The right instrument summons the right servants; maybe an invisible tailor, maybe a magic war elephant (or not), maybe an enchantress. A long game, but very completable.

Anchorhead (#2) vs. Known Unknowns (#21)

Anchorhead is the reason I’m here typing this now. I got one of the first ipads when they came out in 2010, and I needed something to play on it, so I searched ‘Zork’ and found Frotz. I loved Curses and Anchorhead and Not Just Another Ballerina. But then I played Vespers and Varicella and they creeped me out so I gave it up for five years.

Then one day, in 2015, I remembered playing Anchorhead, downloaded it and got back into IF.

For one of the most popular IF of all time, it is very niche. It is a Lovecraftian horror puzzle game set in a big city and gated by the passage of time. Each day that passes (over around 3 days total), the world and the people in it change a bit more. The puzzles are (almost) all in service to the plot. There is a lot to admire here. Due to the small size of IF as a field, there just really aren’t that many games to compare it with in terms of length, polish, story, and puzzles; very few games succeed in all these categories. However, its popularity has led to a backlash and several negative reviews and breakdowns have been published in recent years.

Known Unknowns, on the other hand, is a coming of age story from the same author as Birdland, earlier in the competition. This is a complex Twine game with a wild cast of characters. It combines a haunted mystery with a teenage girl’s experiences with betrayal, understanding her own sexuality, and her place in the world. I think its high ratings on IFDB are due to the resonance people find with their own life stories. The writing is top-notch, and the characters are memorable and distinct (including one that speaks only in emojis).

Known Unknowns will probably appeal strongly to fans of Birdland and Grown-up Detective Agency.

This is a pretty lopsided match in terms of rankings, but opinions have shifted a lot over time and I think many players will enjoy trying both games.

Alias ‘The Magpie’ (#16) vs. Cragne Manor (#6)

This is a great matchup for people who love fun parser games. We have one large but manageable parser puzzler by a single master comedian and author vs a giant mishmash of a parser behemoth patched together by 80 authors.

JJ Guest is an author who likes to let things cook for a long time. This game was 11 years in the making. It’s big; I’d say it takes around 3-4 hours to complete. It’s a Wodehousian comedy where you play as a gentleman thief who has arrived at a large manor house to rob it blind.

There are a lot of fun mechanics like switching disguises and a cast of characters straight out of a BBC comedy that react and move from place to place. The humor is participatory; you can’t really solve the puzzles without setting up some fun punch lines. This is a game in the tradition of ‘highly polished, focused parser puzzler comedies’, like Lost Pig, Violet, or Zozzled, but distinguished from them by having more puzzles and being longer. A definite treat to play.

Cragne Manor is a wild experience unlike anything else, although several have sought to imitate it since its release. It was designed to honor Anchorhead’s 20th anniversary, with Jenni Polodna and Ryan Veeder coming up with a plan for a mega game: they’d write up an overall structure with different ‘puzzle paths’ and anyone who wanted to could write up a room in one of the puzzle paths, or, if they didn’t know Inform, they could describe a room and have the organizers code it.

80 people signed up, far more than originally intended. The variety in experience was astounding; some people made their very first Inform code ever, and some were experts with 25 years experience. Some (like me) spent only a small time on a small room, while others wrote entire mini-games with rooms within rooms (one pair wrote 60K lines of code for their two rooms!).

The organizers decided not to fix bugs or polish rooms except when absolutely necessary. So the game is, by design, extremely uneven. You can hit very difficult puzzles early on that gate your access and feel unfair, only to come across a long story-based segment about stealing an erotic lion book, only to enter a miniature world where you create life and have it fight other organisms like Pokemon. There is no coherence, and that’s the best part of all. To the end of my life I will remember and be traumatized by the rubber bathroom horse. For new players, you will be unlikely to finish, but a good starting area is the region west of the bridge, which can be completed (minus the parts relying on items from other regions) in a few hours.

Make It Good (#33) vs. Worlds Apart (#14)

This is the old-school bracket, a matchup between two of the highest quality games belonging to an older style.

Make It Good is actually fairly recent, from 2009, but it leans towards an older style of gameplay when it imitates Infocom games and has a Tough forgiveness rating.

This is a Jon Ingold game, a name we’ve seen a lot before, with Mulldoon Legacy and Shadow in the Cathedral. This is a hard-bitten detective story, with you, a deadbeat detective, being given your last chance to solve a murder before being thrown off the force.

The game is extremely well polished, with multiple configuration settings, boxed quotes, and a context-sensitive set of hints put into a large-than-usual status line.

The writing is evocative:

>x bottle

“Uncle Stan’s Golden Malt”; yeah, it’s bargain bin liquor at 80% proof and 80% off. Your body’s crying out for it. To slip back, let the whole goddamn world ride all the way to the glass at the bottom. Oh yeah.

It is a difficult game. It’s not too long, but it requires a methodical eye, careful note taking and some good intuition.

Worlds Apart, on the other hand, is a very long game that is designed to have milder puzzles (although I wouldn’t hesitate to use occasional hints; in replaying the beginning of the game for this essay, I struggled because two closely related words have very different results). It’s a heavy worldbuilding game in TADS, the result of decades of worldbuilding and written in place of a novel.

This game is set on an alien world with many species, and has its own forms of magic and science. An excerpt:

You see a tall figure covered in black robes, the only parts visible its head, and a bony arm lifted at you as if to warn you against proceeding further. While it is Dyra in form, you hesitate to call it human: its features are a grotesque distortion of human features. Its face protrudes unnaturally far, coming almost to a point, like the raptor-illusions warriors use to scare outsiders.

The game passes through many days and reveals a lot about the world’s culture, yet the story promises a sequel that never arrived. But her game has continued to please and inspire many others.

Photopia (#49) vs. Digital: A Love Story (#64)

This is a great matchup, because this is a pair of emotional stories that use generally similar techniques, although very different media.

Adam Cadre had a background in film, and used a lot of techniques from film in Photopia. It uses color a lot (if you play a version without color, I recommend switching to one that has it), with nice color transitions for different parts of the game. It also reminds me of Citizen Kane (in a literal way, not as a symbol for all film) in that it tells the story of one very important person from every perspective except their own. Alley, the main character, tells us magical tales which are intercut with scenes from her own life. It is also exquisitely polished; I remember reading Adam say that he spent six weeks doing almost nothing but working on the game every day. It includes features like dynamic mapping so you always just so happen to stumble upon the next important area.

Photopia was widely credited at the time for changing IF (some called it ruining) by being a puzzleless story (although by modern standards it has several puzzles) and by focusing on story more than puzzle. I personally have pointed more towards A Change in the Weather as influencing the story-based boom and Drew Cook has called out In The End as a big influence in serious, puzzle-light stories. But Photopia took both trends and pushed them into the mainstream, becoming the biggest IF phenomenon by several measures. Winner of numerous XYZZY awards and the 1998 IFComp, it has also placed first, second, or generally in the top 10 of several iterations of the Interactive Fiction Top 50. It has the most ratings on IFDB and the third most reviews (after Lost Pig and 9:05). In the end, it’s a story designed to make us love the protagonist, using every stylistic technique it can.

Digital: A Love Story is similar in its intent: to make us love someone. This was the only game that I hadn’t played before this competition, as I had thought it was commercial. It was also, before this point, the most-rated and highest-rated game on IFDB that never had any reviews.

In it, you play on a simulation of an old Amiga computer (called an AMIE computer) that your teacher helped you set up and which contains a dialer system to reach local BBSs (making this the second game in the competition to have a fake BBS, after Endless, Nameless). Once you dial in, (having to type all numbers manually), you encounter the wild days of the early internet, with fandom fights, hackers teaching you how to abuse the phone system, and random philosophers or educators sending their complex texts into the ether.

You also meet Emilia, a burgeoning poet eager for feedback. The two of you begin to communicate, and things begin to blossom. But the further you go, the more the game evolves, including in some unexpected directions.

Dialing codes is the main interaction in the game, as well as choosing who to reply to. The smart part about the game is that it avoids showing your text altogether. Instead, it only shows replies, requiring you to infer what you might have sent.

The game did inspire some strong emotions in me, including panic. It can be time-consuming to type the codes, but I was able to complete the game in a couple of hours.

Both games are about piecing together information about a young woman that you are meant to love, making this a great matchup against each other.