So, after 12 hours of sleep I’m back at this.

I think one thing that people who grew up playing and writing parser games lean on is that world-model. They’re used to playing and making puzzles that are object-oriented - find the key to open this door. That’s the paradigm that works best in parser and there are lots of games that are basically “PC explores a mostly abandoned area to figure out what happened, and often overcoming obstacles to make progress and proceed to other areas.” A world model is awesome for this.

The Toothbrush Problem

I frequently bring up what I call “The Toothbrush Situation” which is a conundrum parser authors run into: A parser author wants the player to brush their teeth and goes about simulating all the moving parts. A brush is an object with attached bristles as a supporter to hold the paste. They restrict with a rule that nothing but toothpaste can go on the bristles. They then implement a container of toothpaste and toothpaste as a liquid using a plugin that simulates measured liquid - so there’s only so much toothpaste they can use! Then they implement a separate cap that can be UNSCREWED to remove it from the tube! Then they have implement the PCs mouth and teeth as an incorporated container containing teeth so the player can type TAKE TOOTHBRUSH. UNSCREW TOOTHPASTE CAP. SQUEEZE TUBE. PUT TOOTHPASTE ON BRISTLES. PUT BRUSH IN MOUTH. BRUSH TEETH UP. BRUSH TEETH DOWN. AGAIN. AGAIN. AGAIN…

Is this fun for the player? Perhaps in an absurdist game about dental hygiene, but if the player is required to have minty-fresh breath before leaving the house for work, they’re gonna get stuck here. Even though they know how to brush their teeth in real life, parser implementation can be fiddly because of guess-the-verb/noun - they may get stuck on what should be a simple task.

This goes back to “What’s most important in IF?” to which the answer is story. Is brushing your teeth such a mammoth task that it requires this much work and testing by the author? In 99% of the cases it’s better to just implement an action >BRUSH TEETH and be done. Or even better, perhaps just narrate in the bathroom description “You take care of all your grooming and hygiene, including brushing your teeth.”; now the player is minty-fresh. Parser authors often cast themselves as the player’s adversary, throwing puzzles and obstacles between them and the story. I find the opposite true. “Always be on the player’s side.” Even if this means helping the player when it’s obvious they know they want to do. In the original Curse of Monkey Island where the player has to row a boat around a group of islands top-down to access different locations, at one point the player must collect several items from different locations and bring them to one location for a puzzle. After the player does it once and sets out to get the next thing, the game interrupts with a title card “After lots more furious paddling…” and puts the player where they need to be, shortcutting tedious back and forth. The game knows what the player wants to do, the player knows what they want to do, and the creators took advantage of that and jump-cut like a movie. This is encouraging to the player - instead of saying “they need to complete all parts of my multi-tier devious puzzle!” you work with them in service of advancing the plot and reducing tedium.

In a choice narrative, without all these tools the author can make a link [[Brush Teeth->minty-fresh]] and that’s it’s. A flag is set that the player can leave the house.

Puzzles aren’t always the reason to play IF. Contemporary IF has shown there is so much more that can be done. Rooms don’t have to be rooms - the player can explore a realized simulation of their mind, with thoughts and concepts as objects that are traded.

I’ve seen people discuss “What Classic IF would make a great movie?” and the answer is very few of them because movies aren’t usually about people finding keys and unlocking doors all by themselves. Movies require characters and often dialog and character arcs and conversations. This is what parser IF is not inherently good at. There are great conversational parser games, but it’s really difficult to make one NPC seem realistic and go about their day and converse with the PC, much less a whole cast of characters. Most NPC’s in parser aren’t autonomous, and they are there to ask the player to do things. Often you’re like “Bob, the frazzmawhig is two rooms away, why are you questing me to fetch it for you when you’re just sitting here drinking coffee?” You seem like you want to talk to Bob, but I didn’t understand that sentence… Many parser authors find difficulty with ask/tell and instead will implement choice menus. Why would they do that? Because limiting what the player can do can make it easier to tell your story.

Not to say there aren’t great conversational games with characters. Everybody fell in love with Floyd from Planetfall, but he’s a robot who understandably has a limited vocabulary and just follows the player. In Counterfeit Monkey, the player has two characters in the PC’s head as a magical amalgamation of both and it’s narration instead of implementation.

The paradigm for choice-narrative is passages which can be thought of as “pages”. In quality-based-narrative (QBN) the passages are often thought of as “cards” which can be shuffled. And the passages needn’t be forward-moving and linear. Please review this very fine article describing structures by Sam Kabo Ashwell:

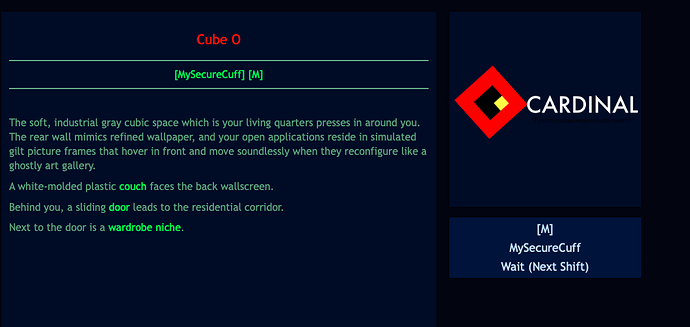

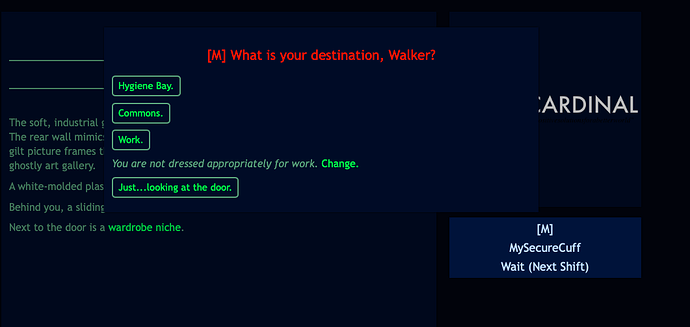

How do you create a world model? Forget the compass directions. You just make links to other “hubs” which can represent other locations, or events. Here in robotsexpartymurder (note game NSFW - these examples are all safe) you click the “door” link and are asked where to go. In parser you could very well think of compass directions as a choice menu. “Which way to go from here? The Hygiene Bay is to the north, The Commons is to the West, your Workplace is to the East…”

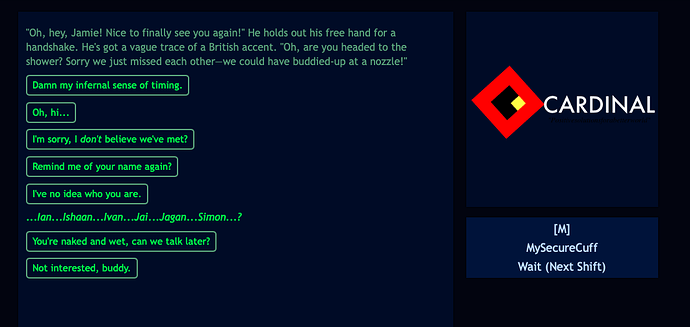

But instead of leading merely to a location, it can lead to an encounter. In this case, the first time you leave your living space, you run into a neighbor.

Choice narratives are great at conversational games that can remove the necessity of moving through physical space. When I initially reviewed ChoiceScript (which is Choice of Games engine for their very popular commercial IF) my first bafflement was “how do I make rooms and objects and keys?” The simple answer is you don’t - CoG focuses telling stories which read like books and are narrative rather than object-driven, and allow the player to co-create and affect the plot usually through higher-level decisions. You’re not finding keys to unlock doors, you’re deciding who to align with, what the economic system for the kingdom will be, and as you read, the story may change based on the choices. Usually the game isn’t about what room you are in when you >FROB THE JAZZMAWHO but relationships and higher level plot decisions.

This requires thinking on a higher level when creating a story. The player’s choices aren’t as granular. This also requires getting out of the “time cave” model where every choice branches and causes combinatorial explosion. How do yo do this? By considering variables or qualities, and creating hubs.

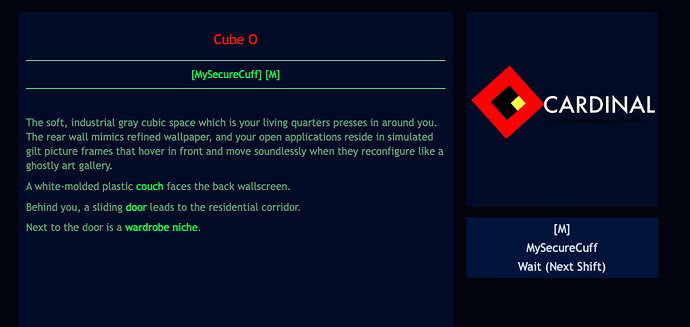

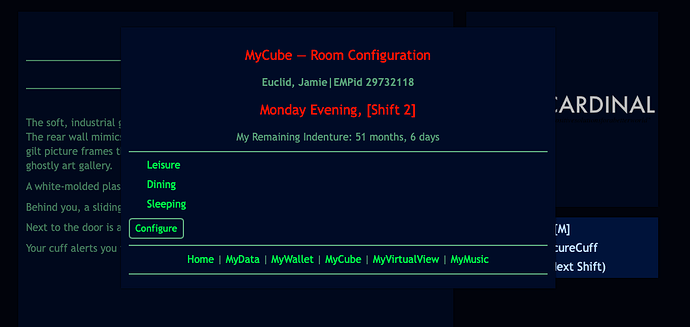

Here’s the main hub in RSPM. You can think of it as a room.

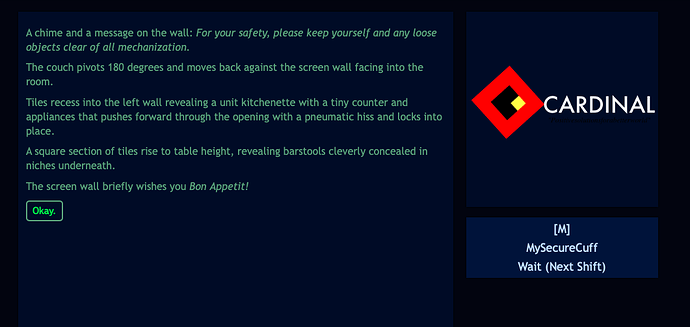

I can reconfigure the room to change it. Stylistically you’d have a “kitchen” room to walk to, but that’s not how this game works.

There’s no bathroom. For that, the player must routinely take care of their hygiene in public facilities. There are a few choices, the game assumes the player brushes their teeth as they click to grind through the ritual. (The company knows this and will nag if you let yourself become less than minty-fresh.)

Instead of making a couch, I give the option to link to [couch] where you are then given the option to nap (if the fatigue stat is high enough) turn on the TV and pass time, or if someone else is with you in the room, they will join you and there are conversation options. The player needn’t guess what to do in this “location” since they are explicitly instructed by choices what they can do. This may seem limiting, but the player isn’t going to get stuck. I don’t have to worry about a refusal to EXAMINE COUCH CUSHIONS because there’s nothing there and no point in offering that option.

The trick here is there is a moving game clock. Different options will become available at different times of day. If the player buys a snow globe elsewhere, it’s automatically added to the room with a link to examine or admire the snow globe. In RSPM it’s possible to hammer WAIT and get to the end of the game, but where’s the fun in that?

While most people consider choice narratives linear, they can be designed where the player moves around “hubs” which are basically menus with options in each location. This may seem limited, but it’s actually very freeing to have more control as an author. And it majorly reduces testing and debugging.

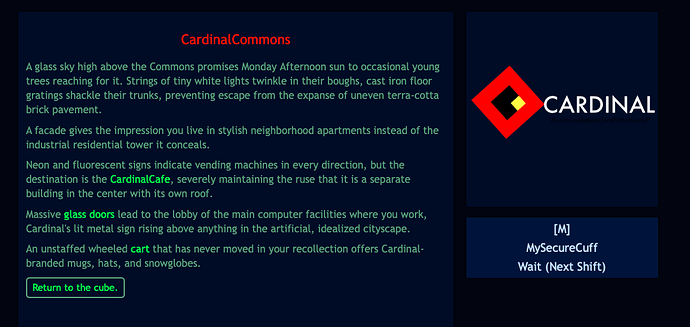

Here’s the Commons:

That’s very similar to a parser description. Instead of typing GO CARDINALCAFE the player clicks. The cart is a shop - click cart and infer EXAMINE CART. There’s also a prominent navigational choice “Return to the cube”. Hey, it’s a world model! I don’t get as much choice as I would in parser, but every choice is meaningful somehow and works as intended. Sure, I can’t examine the trees, but they aren’t important to the story here. Everything the player can do is story focused.

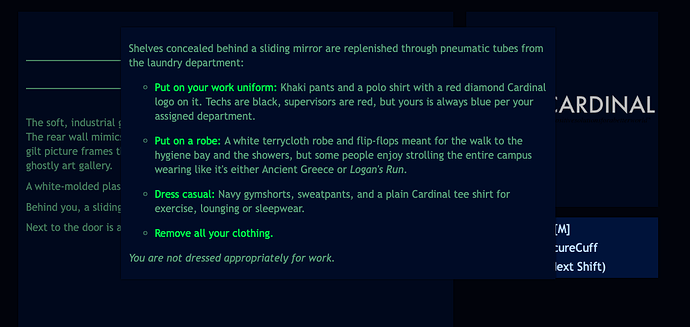

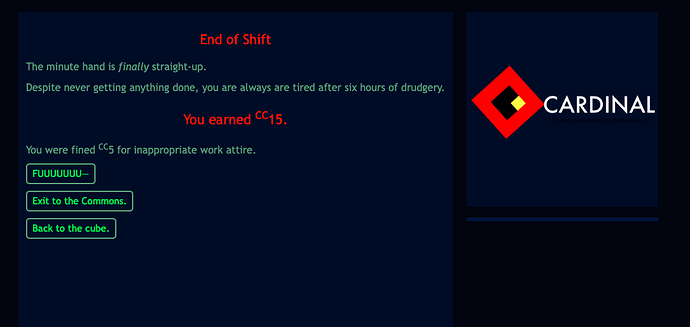

So yes, choice narratives can be linear and potentially lawnmower’d through, but it’s up to the author to design the exploration and set variables. I can buy a coffee mug at the cart, but only if I have enough money. As the player interacts, variables get set which will change things in locations I’ve already been to. In the wardrobe niche link, I can change clothes, which sets a variable that will affect how people perceive me. Em (your very helpful and not at all renegade AI) won’t let me leave my room naked. I can go to work in the wrong clothes, but I’ll be docked for not following corporate policy. Notice the game warns me I’m not dressed for work by checking a variable here.

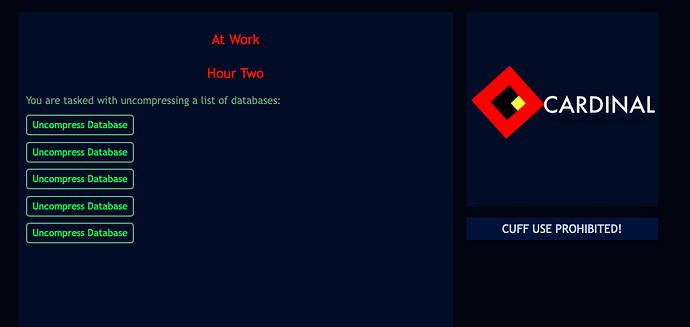

So gameplay and puzzles. If you choose to go to work, you have to grind through several pages of work events. They are randomized so each day is a little different. But it’s busy work that takes up time on the game-clock, and simulates work for the player. I have to click on all these tasks to accomplish them. Not much happens, but I can only proceed by doing this. This is a simple “grind” building up productivity points.

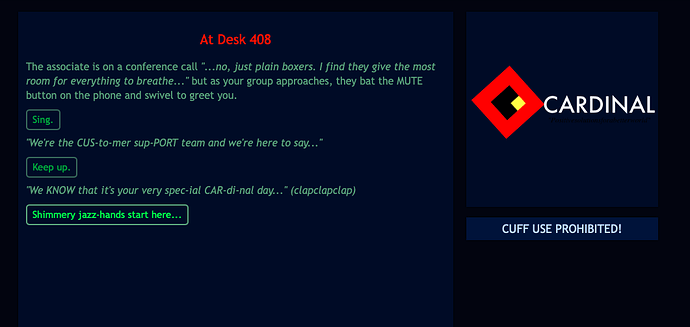

I’m rounded up to sing happy birthday to a co-worker, more grind.

At the end of the day, I could have made more money if I’d remembered to wear my corporate-mandated uniform… I’ll remember that next time.

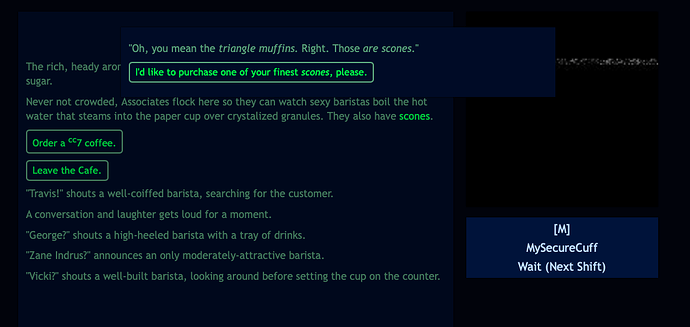

I deserve a snack to make myself feel better, so I’m headed to the Commons and the Cafe.

If you order a coffee, the player must wait through real time as the game throws out multiple orders until your name and drink show up to snag it. This becomes and important later… One “puzzle” is identifying someone you’ve not met in the crowd. The way you solve it is to order a coffee with their name (you type it in, the Baristas usually mangle it) and wait for the person to pick it up so you know who they are and then can subsequently converse with them.

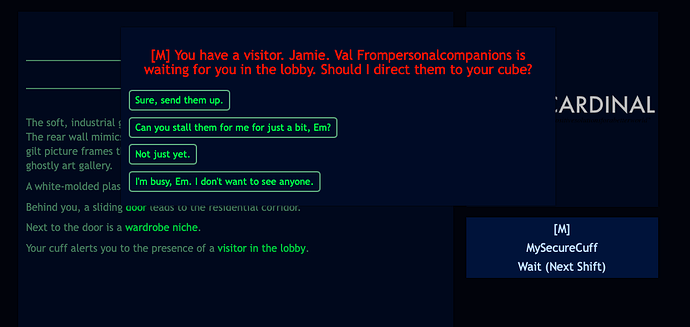

When I get home, I have a visitor. This is based on the time of day and previous choices.

Anyway. That’s world model with characters, locations, events, consequence, and beginnings of plot. True the player’s actual choices are confined at any time to what I have decided they can do at that point in the plot, but I’ve made choices, I made mistakes, I made money, I ate a scone. And the plot continues. I didn’t walk linearly through a time cave.

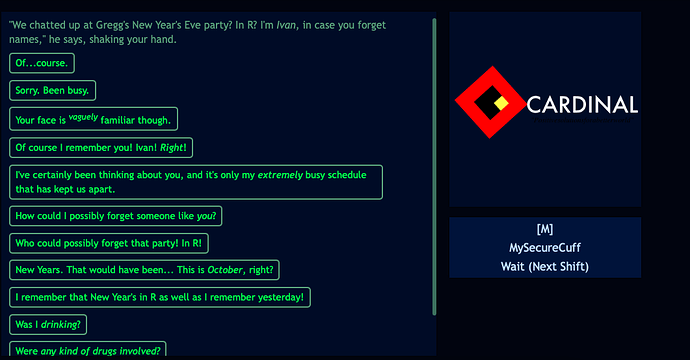

One of my dirty secrets: often I give the illusion of more choice than there is. In this conversation, all the choices here lead to the next node with slight text variation. Why so many? I’m letting the player role-play their reaction rather than steering this actual one-sided conversation masquerading as character introduction. FREEDOM (but not really) Also, I can world build through choices. Without Ivan saying it, there are clues the player doesn’t remember Ivan (though you will on your next play through, and you can use prior knowledge from previous plays) the time of year, and some other minor details about the PC to avoid the player-amnesia situation. It suggests a lot more conversation than I’ve actually programmed.

[Yes, this will probably continue. Probably about boardgames, grind, and “fires in the desert”.]