Now the comp is over, here are my thoughts & ratings of the other entrants. I co-wrote 19 Once and Zugzwang, so I won’t be commenting on either here, but I have a blog post ready with some thoughts (which I’ll post after the results come in).

These are my honest opinions, which are based on my own taste in craft, design and writing. Ultimately, it’s great for people to make things and share them, but I personally have found direct critique more useful than effusive praise.

Overall there were few standout games this year, and nothing like a Chlorophyll or an Oppositely Opal. There were a few interesting (if flawed) works with a unique vision, and several more fairly unambitious classic text adventures. There were also some very buggy messes, including two games which I think I’ve managed to demonstrate were written with assistance from ChatGPT.

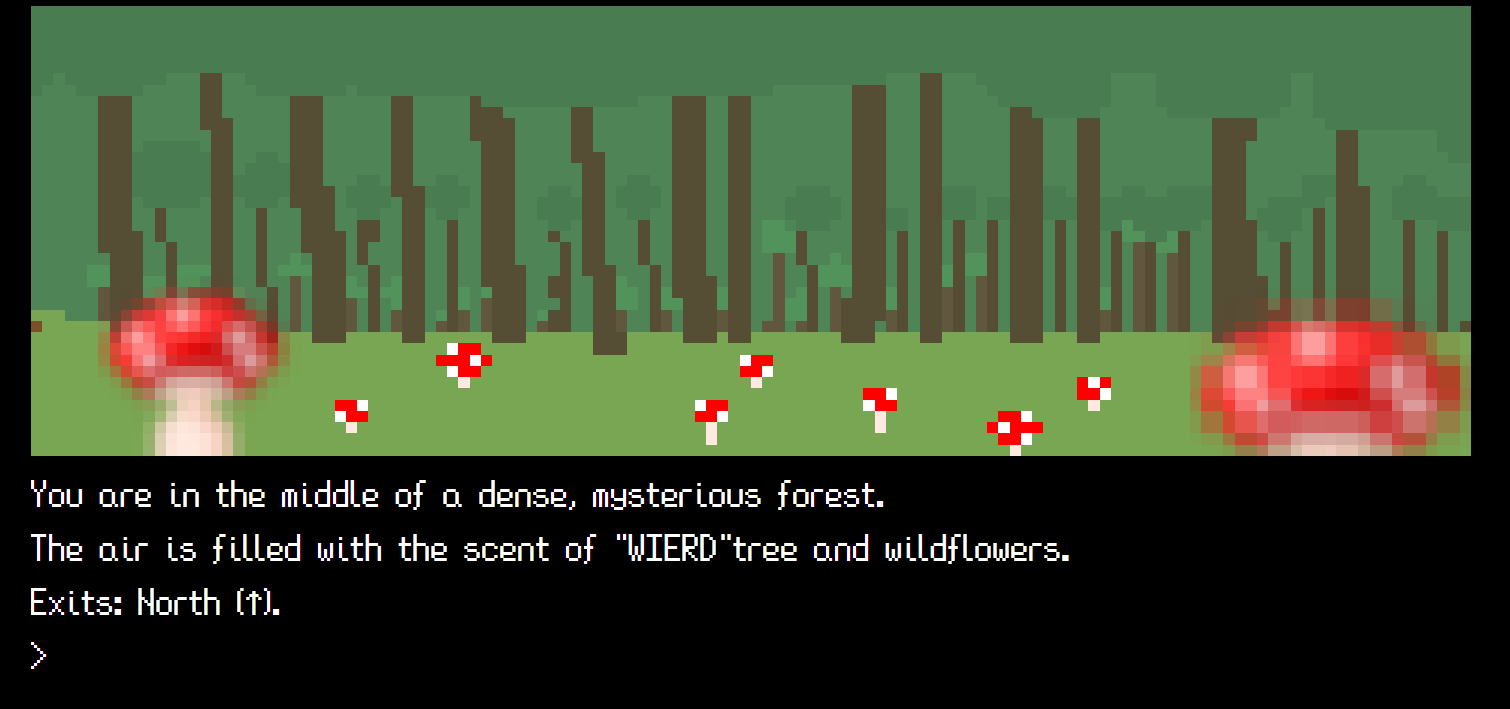

Mysterious Cave

Mysterious Cave

Adventuron test game with dodgy images, prominent misspelling in first object (wierd) and one non-puzzle of a puzzle. Everyone has to start somewhere, but my recommendation is to not bother submitting to a competition the first thing you work out how to do.

The English Restaurant

The English Restaurant

In theory, this game has a neat conceit for a parser that doesn’t understand you very well: set the scene in a situation where you are not very well understood yourself. As a game, it’s looking for specific keywords in natural english sentences and not parser-type commands. So “We’ll have the soup” might work but “order soup” doesn’t. The actual implementation of it as a game is a bit fiddly, you have to type things in the exact order that the author intended (e.g.: you can find out the price of the soup, but you have to find out about it immediately before asking for it, not earlier in the conversation). NLP can be powerful for parsing variable player input (Façade is an example of this), and experiments in new parsers are great to see. As a game, as a literary experience, and as a practise for speaking English language, I’m not quite sure this is there yet.

IYASHIKEI: the Fountain

IYASHIKEI: the Fountain

Apparently I’ve watched one Iyashikei story— Mushishi— which while lacking an overarching plot, has events and story within each episode. This game however, is meant to be purely meditative. There’s a lot of descriptive text, but it tends towards the repetitive painting-of-a-picture, rather than the traditional parser game norm of ‘information about what can be interacted with’. (For example, the shore “invites quiet reflection”, but only the player can quietly reflect and not the character). The score count in the status bar would suggest some game-like goal, but I suspect that it’s an unremoved default.

Perhaps I missed a description, but I had to check the source code to see you could go south from the island shore, but from there the experience was quite straightforward. Overall, the fountain is a very hazy, indistinct place. I think the spiky and unforgiving nature of a parser, where an experience is mostly error messages, works against the desired feeling of quiet serenity.

Moreover, it’s a hazy place because the descriptive text was clearly written by ChatGPT. The first prompt I tried spat out a passage which is almost phrase-for-phrase identical to Iyashikei. The beauty and serenity of something like Mushishi works because it has a vividly well-realised setting with a distinct authorial vision. I respect Adam’s efforts to make something with ZIL, but textually, the result here is ultrageneric LLM blather.

(See the next detail section for a comparison.)

Chat GPT prompt: 'Describe a tranquil forest glade'

ChatGPT

A tranquil forest glade is a serene, open space surrounded by tall, majestic trees. Sunlight filters through the dense canopy above, casting dappled patterns of light and shadow on the soft, moss-covered ground. The air is fresh and crisp, carrying the earthy scent of pine and damp leaves.

The glade is bordered by a mix of ancient oaks, slender birches, and stately pines, their leaves rustling gently in the breeze, creating a soothing symphony of natural sounds. Wildflowers in vibrant hues of yellow, blue, and white dot the forest floor, adding splashes of color to the green landscape.

Birdsong fills the air, a melodic chorus of chirps and whistles that blend harmoniously with the distant, bubbling sound of a nearby stream. Occasionally, the flutter of butterfly wings or the soft rustle of a deer moving through the underbrush can be heard, adding to the sense of peaceful solitude.

In the center of the glade, a small, clear pond reflects the sky above, its surface smooth and mirror-like. The water is cool and refreshing, inviting a quiet moment of reflection or a gentle splash to break the stillness. Around the pond, clusters of ferns and delicate wild grasses sway gently, their leaves whispering secrets of the forest.

The atmosphere is one of calm and tranquility, a perfect sanctuary from the hustle and bustle of the outside world, offering a moment of respite and connection with nature.

IYASHIKEI: The Fountain

You arrive at the island shore, it welcomes you with a blend of soft, golden sand and cool, green grass. Tall, shady trees line the edge, their leaves whispering in the gentle breeze. The water, clear and inviting, laps softly against the shore, creating a soothing rhythm. Sunlight filters through the branches, casting dappled patterns on the ground. Colorful wildflowers dot the landscape, their delicate fragrance mingling with the fresh scent of the lake. The shore invites quiet reflection, its beauty a tranquil retreat. Here, surrounded by nature’s serenity, you feel a deep sense of peace and connection to the world around you.

The clearing is a tranquil haven, bathed in dappled sunlight filtering through the canopy of ancient trees. Soft moss carpets the ground, cushioning each step and inviting you to linger. Wildflowers in vibrant hues dot the landscape, their delicate petals swaying in the gentle breeze. In the center, a natural fountain changes colors, casting a mesmerizing glow.

The Postage Code

The Postage Code

Having the player post packages can be a good prelude to something more if there’s a twist, but unless I’m missing something, this game basically plays it straight— you post packages. The art was well drawn with a charming style. Typing full commands with no scrollback made the experience more tedious than it had to be.

Mystery Isles

Mystery Isles

I was impressed with how dedicate the author was to implementing on so many different systems. This is a thinly implemented classic puzzle adventure, of the sort that was common on the ZX Spectrum in the late 80s and early 90s. Go to a place, get an item, use it on something. Being stranded on an island could be a good hook for a mystery, but like its classic forebears, this game doesn’t do very much with the premise.

Paranoia

Paranoia

This is a neat idea— implementing a “spot the difference” puzzle in text. The implementation was sometimes frustrating— being encourage to interact with a dozen nouns with five senses, 13 times, with the whole game resetting every time you make a mistake, but frustration was somewhat ameliorated by having most of the differences be quite obvious. The game ultimately works on the verve of the different unusual discrepancies, though it could have done with a stronger beginning and ending to tie it all together.

Beef, Beans, Grief, Greens

Beef, Beans, Grief, Greens

This is very similar to Andrew Schultz’s many other wordplay games— in this one you’re looking for alliterative rhymes. It has the extremely granular hint device similar to earlier games. There’s a basic story throughline here, but it’s very much in service of the wordplay. Once I worked out what the concept, I rattled through a good part of it. (Eventually consulting the walkthrough, there are definitely some slang words which I wouldn’t have independently have guessed except out of alphabetical exhaustion). To a certain degree it can be brute forced just by going through your keyboard (Vade Vug? Nade Nug? Ah… Made Mug).

The joy in this game is in the unique responses for all the weird and wonderful combinations. In a way it’s the complete opposite sort of approach to the slapdash ChatGPT prose some other authors are experiminting with— it has its own unique voice. I’ve got a lot of respect for Andrew’s craftsmanship but I think sometimes the exhaustive completeness of the mechanic detracts from the puzzle— some of the pairings are both individually strong, but others are a stretching strain/retching rain/sketching skein.

(Playing it makes me want to try something wordplay-based myself, as its so well suited to the parser… perhaps we could work together sometime to make the next Ad Verbum??)

Yurf

Yurf

Remarkable single-word parser. Very slick interface. Lots of nice shortcuts (though strangely not L for look). The setting is your typical Alice in Wonderland or Phantom Tollbooth kingdom, with a number of distinct characters, songs and the like.

The implementation of the single-word parser is interesting in that it echoes the streamlining of interaction in graphical adventure games, but in the complete opposite direction. In many modern point-and-clicks like Journey Down, Broken Age etc., there is only one verb, one mouse click, and it does whatever the obvious action would be. You can’t even examine. Yurf is the mirror image of this approach: you can use many different verbs, but the game selects the object! It’s quite sophisticated in this, as when you type your action, it unpacks it and tells you what the full action would be before you select, so it doesn’t entirely feel like smashing around with your eyes closed. I like how it plays with this (e.g. “jump” becomes “leap into the expanse”), even sometimes diagetically in the text itself in various gags.

I played to completion, though not the boss mode. I recommend this one.

Samurai and the Kappa

Samurai and the Kappa

This game has an interesting relationship to mimesis. It’s very much a game of two parts. The first part is a puzzleless tutorial about following cultural rules; the second part is a series of puzzles with little rule following (other than observing the priest’s ritual).

In the initial tutorial section at the inn, the player’s action is entirely dictated by what is culturally expected of the samurai character. For example, the player must take off their shoes before entering the inn. The game throughout is richly researched, though written very much in an edutainment register.

In the second half, the player does three of what Roger S. G. Soralla, in his seminal essay “Crimes Against Mimesis”, called “Puzzles Out of Context”. The player has to solve a logic grid puzzle, a Nurikabe puzzle, and a maze with room names all alike (this isn’t a spoiler, the game’s main page explicitly warns you that these are coming). To Garry Francis’s credit, all three puzzles are somewhat embedded in their setting, though their presentation in each case quite literally takes you out of the game. In the two logic puzzles, you go away from the game and fuss about in an abstract grid and then go back to the game and enact the solution; in the maze, you’re encouraged to make a map. Map making is a time-honoured adventure game tradition, and one of the game’s goals is to teach players somewhat to play adventure games, so I can’t really begrudge this one. However, the overall effect is to repeatedly step out of the story and think as-a-player, rather than as-the-character. And this is in sharp contrast to the initial, more setting-grounded, section.

Of these puzzles, the logic grid is the most egregious, as 1. There’s no in-world universe reason why each villager would be so miserly with information. 2. You start learning the clues before you even know why you need to learn the clues. 3. This learning-of-clues is even encouraged explicitly by the village elder, again, before you have any earthly reason to do so. All this means that the villagers who you might otherwise be sympathetic towards become reduced to rigid clue dispensers. The author was explicitly experimenting with something new with these puzzles, and that can itself be commended.

In the second half, the social rules have mostly been forgotten about, the player needn’t remove their shoes before entering any of the huts (though perhaps those rules don’t apply to commoners). The overall parser implementation was competent (though the combination of “talk to” and “ask” conversation systems was somewhat inelegant).

There are a lot of period-appropriate details in The Samurai and the Kappa, and the game invests the most detail on three of them: the specific myth of the Kappa, temple rituals, and child prostitution. The first two are intertwined with the game’s puzzles and plot and make the game a distinct experience. The third is a period detail that the author was especially interested in exploring but has no impact on the plot or puzzles, though maybe we can say that it is used as a way to teach new players how to use the parser.

Mike Russo in reviewing Murder Most Foul (David Whyld’s entry in last year’s competition), says “if you include slavery in your game, it isn’t a game that happens to have some slavery in it, you’ve now made it a game about slavery” and this year he made the exact same point about child prostitution in Samurai and the Kappa. I’ve included the relevant segments below:

ask maid about room

“Your room is this way.” She points to the east.e

You should talk to the maid to get directions.ask maid about directions

She just giggles. “I’m sorry sir. I’m just a simple maid. I don’t know anything about that.”enter bath

You step into the bath and soak in the near scalding water while Mokuko scrubs you clean. She’s very gentle, even sensuous, and you completely forget about your nakedness and vulnerability.When she’s finished, she giggles and says, “All done”, then waits for you to get out of the bath.

x maid

Mokuko is very pretty, but she looks too young to be a maid. You wonder how old she is.ask maid about age

“I’m 16 sir, but I’m very experienced.”exit

When you step out of the bath, Mokuko pats you dry with a fluffy towel. She seems a little shy and tries to avoid looking at your private parts. “It’s a bit late now”, you think to yourself. “She’s already seen everything.”As soon as you’ve finished your meal, Mokuko collects the table and the empty bowls and takes them outside the room. She then returns, bows deeply and asks if you require any extra ’service’.

[When someone mentions something interesting, you should ask them about it. In this case, ASK MOKUKO ABOUT SERVICE.]

Mokuko parts the folds in her kimono in a suggestive manner to reveal the cleavage of her petite breasts. The poor girl looks like she’s barely out of puberty. You bow and thank her politely so that she won’t be offended. You tell her, “I must preserve my strength, as I need to look for

work in the morning.” With that, she covers her breasts, bows and shuffles backwards out of your room, leaving the sliding screen closed in her wake.sleep

You settle down for the night, but find it difficult to sleep because you’re being eaten alive by the fleas that have taken up residence in the tatami matting. Just as you start to doze off, you’re woken by squeals and giggles from your neighbour’s room. He has obviously decided to avail himself of the extra service provided by his maid. When the couple next door have finished their amorous activity, you eventually fall asleep.…

talk to man

“Good morning. Are you ready to leave?” You nod that you are. “Let’s see now, you didn’t avail yourself of the extra service, so your bill is one silver coin.”

A game is mostly about what you do in it. This game is about being a stoic samurai who turns down a child prostitute and then does some magazine puzzles to save a missing child from a supernatural beast.

Alphabet City: The Parser Edition

Alphabet City: The Parser Edition

Everything good about the game is in the idiosyncratic scenarios, from what I assume were taken directly from its earlier choice-based iteration. Given the title, I’m assuming this game has been translated from another format— the author appears to have a lot of other titles. Everything janky is due to its spotty translation to a parser game. The good thing about knowing it’s based on a choice game, is knowing that everything can be solved just be going, examining and taking. This takes a lot of the friction out, as there’s no “guess the verb” problems. In the Club it’s apparent there was meant to be some kind of puzzle, but it doesn’t appear to have been implemented.

Playthrough 1: I took all, took a moth and died.

Playthrough 2: I picked up and dropped my beer bottle five times and then won the game

Playthrough 3: I drive my bike down onto the subway, and ride the train to the club, where finally I dismount before entering. At the club I take everything: the bar, the DJ booth, the stage, the walls, two separate crowds, the velvet rope and even the air. I eventually make my way to the confrontation with Jayne, but she’s not actually there and there’s no way to retrace my steps through the club so I’m forced to restart.

Playthrough 4: This time I take the offramp to Jersey, kidnap a squeegee kid and some junkers, and haul ass to the SCREEM building. The motorcycle throttle is giving my disambiguation problems so I have to drop it at work, and so then, after picking up a job, I head back to town. Jayne still isn’t at the club, so I give it up.

The game has a lot of character and specificity of place. You’re not standing outside of it, detached, but a visceral part of it. Unfortunately, this isn’t very well implemented for the parser and is a bit too broken at this stage. With a bit more technical chops, the author could make a great game, there’s no doubt.

Final note: the author has done a good job selecting AI-generated illustrations so they’re not too obvious, but the jig was up with the word “THE” in the Mudd Club sign. I naturally wondered whether the descriptions were made using ChatGPT and I’m pretty convinced they were. See the comparisons below.

Unfortunately for the authors of Alphabet City and Iyashikei, writing with ChatGPT is a bit like making theatre backdrops from cereal boxes. Just moving across the stage causes the shaky façade to fall apart.

ChatGPT prompt 'Describe the Mudd Club in New York as a text adventure room description'

Alphabet City’s Mudd Club

The Mudd Club is a gritty, iconic venue. The air is thick with the smell of sweat, cigarette smoke, and the faint scent of alcohol. The walls are adorned with eclectic artwork and graffiti, creating a moody and intimate atmosphere. The dance floor is a chaotic blend of bodies moving to the sounds of punk, new wave, and experimental music. A DJ booth commands attention with a turntable and a collection of vinyl records. Bands perform on a small stage, creating an intense and immersive experience. In the back, there’s a bar where patrons can grab a drink. The crowd is a mix of punk rockers, artists, and fashion-forward individuals.

ChatGPT Mudd Club

The Mudd Club is a dimly lit, smoky nightclub buzzing with raw energy and rebellion. The walls are adorned with graffiti and peeling posters, while a punk band thrashes on a makeshift stage, filling the room with loud, discordant music. A diverse crowd of punks, artists, and misfits throngs the sticky floor, their eclectic outfits illuminated by flashing strobe lights. To your left, a narrow staircase leads to a shadowy, exclusive upper floor, while to your right, a long bar serves drinks to patrons who move with the rhythm of the night. The atmosphere is electric, tinged with the excitement of the unexpected and the unknown.

Project Postmortem

Project Postmortem

This was a very short game, well described and implemented, with a distinct plot and setting and character motivation and exactly one puzzle. It would have made a fine first scene in a longer game.

Race against Time

Race against Time

My network thought there was a virus in the adrift runner and I couldn’t get the blorb to run on Windows Glulx, but eventually I got things running.

This game was quite a technical slog of searching stuff for keys to unlock doors to rooms where you’d search stuff to get keys etc. There wasn’t much of a race against time, as I sedately combed the corpse-filled place.

I almost left this one unrated as it was quite boring. I considered I’d give it another try and checked the walkthrough to see more of the game. I requires an author mind-reading action that is as far as I can tell completely unmotivated and unhinted by the text (moving the papers on a desk). Given an absence of any real puzzles, and staring at a future reliance on a very long walkthrough, I decide to give up. If a game is mostly about what you do in it, this game is about emulating the escape-room feeling of ransacking the furniture for the next puzzle piece.

Return of the Sword

Return of the Sword

My computer deleted the .exe as I was running it, as it considered there to be a virus in it, then later it automatically deleted the zip when I tried to redownload. Hopefully this is a false positive, but either way I was unable to proceed. What I will say though was that the author has clearly and competently signalled it as a classic “old school” text adventure in the Lazy Anachronism mode. Arthurian legends, modern technology, old game references… Everything I could say about all this, was already said three decades ago in Crimes Against Mimesis. I’ve put out much the same position in my Embedded Puzzle Manifesto, and revisited the arguments of tone in my recent piece about Zaniness. Beyond the unambitious narrative framing, what I played of the game was confidently implemented.

Free Bird

Free Bird

I didn’t have PyGame installed and didn’t particularly think it worthwhile as the author said not to bother with the game in the game’s description. I didn’t rate it but was tempted to give Free Bird a 1 star on principle for repeatedly telling the player that the game is not recommended. If you know your game is bad, don’t enter it into competitions. You can archive things without doing that.

Moon-House Technician

Moon-House Technician

I couldn’t get it to run, so didn’t rate.

Brief thoughts

A good text game ideally…

- … has a coherent setting where the parts don’t tonally work against one another

- … has some kind of plot and characters

- …shows some ambition rather than just doing something that has been done many times before

- …has distinct, hand-crafted prose

- …isn’t too buggy

- …gets the player doing something interesting with their time

- …draws you in to its world

And if a game is ambitious enough, I’ll forgive it a lot else.