THE SHORT VERSION

I’m not very good at saying things directly; I prefer to dress them up in stories and let people make of the anecdotes what they will. So we’ll open this postmortem with one such story.

Once upon a time, many bad things happened to me. When I was telling my friend about one of them, she said, “I’m sorry that happened to you.” And me being me, I replied, “Do you mind using a different phrase? Maybe, I’m sorry you had to deal with that or I’m sorry you went through that or wow that sucks – any of those would be fine.”

I’m aware that I’m not the hero of anyone’s story. But even if I’m not the hero, at least let me be the protagonist of my life. Let me deal with things; let me endure things; let me go through them. Don’t let them happen to me as if I’m already stretched out decaying in the ground.

And that’s pretty much all there is to the game. Could’ve saved myself a lot of hours by writing that instead! So thanks for reading, and as a special reward, here’s my playlist for January. Once again, me being me, it’s a playlist of poetry, not music. ![]() Enjoy!

Enjoy!

THE LONG VERSION

Before we get into the meat of it, a clarification: I’ll use January to refer to the work as a whole (which I will also call a story, a game, a thing, whatever) and January to refer to the protagonist.

Also warnings for spoilers and for very frank discussions of suicide, gore, bodily functions, vulgar language, etc.

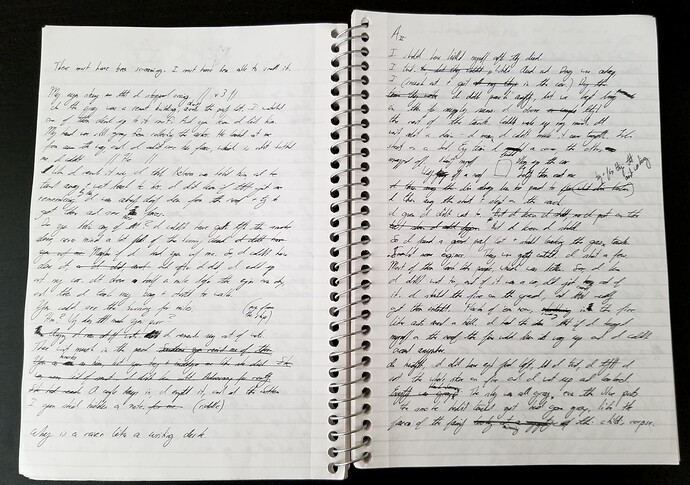

So January’s story has been kicking around in my head for some time, maybe 3-5 years, but I couldn’t find a good reason to share it with other people. It was just another apocalyptic story about some sad guy, a genre woefully oversaturated and out of vogue even five years ago. Some of the scenes survived from early drafts nearly verbatim (including the opening line, which has never changed), but most did not. For example, in the canonical version of the story (yes, my personal canon is different from my published canon), January finds a dog as well, who is a perfect delight. But Dog’s arrival botched the pacing of the story and sweetened the scenes too much, so she had to be cut.

Anyway, while I was nudging the idea of January’s story around in my mind, two things happened. First, I was working on a research project about how people cope with major life shifts, especially illness, via storytelling and the re-imagination of self through narrative [see: The Wounded Storyteller by Arthur Frank]. And second, the many aforementioned bad things happened to me. Between my own experiences and the narrative theories I was studying, I felt that I could do something meaningful with January’s story. I wanted to use interactive fiction to show the linkage between moments across time and between the internal and external self, in ways that linear prose can’t.

As a result, I think of the story as functioning on three-ish levels.

Level One

First, there is the literal plot. As many reviewers noted, this is the least important of the three. Guy survives apocalypse; his brother and sister-in-law get infected; he feels mortally responsible for their deaths, but can’t quite bring himself to commit suicide; he spends the next year working through the guilt and grief; he adopts Cat along the way; eventually he returns to the other survivors and resolves to stay alive for now.

Happy to answer specific questions about the plot, if folks are curious! But I won’t bog us down with details here.

Level Two

Second, there is the meta plot. As mentioned above, January is a story about storytelling, or more precisely, it is a story about how autobiographical storytelling assists in reforming the concept of self after a major life rupture. Hence the epigraph of the game:

One of story’s primary purposes is to lay claim to experience. Autobiographical storytelling can take personal experience back from silence, shame, fear, or oblivion. It says, “I cherish this” or “This haunts me.”

It asserts the significance of events in one’s life: “This happened to me.” “I did this.” “This is part of who I am.” “This should not or will not disappear, and I act to preserve it by turning it to words and shaping them as story.”

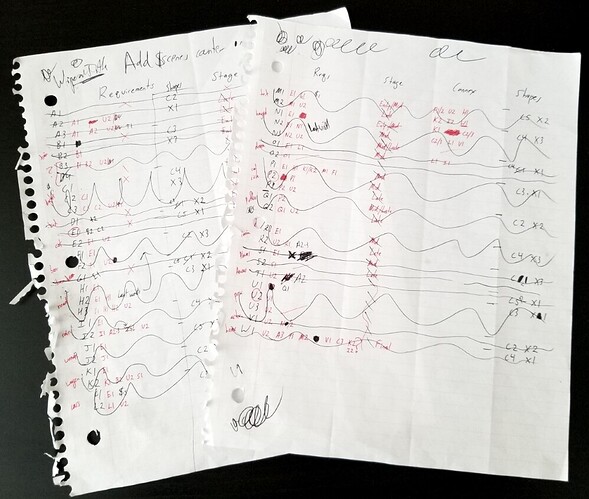

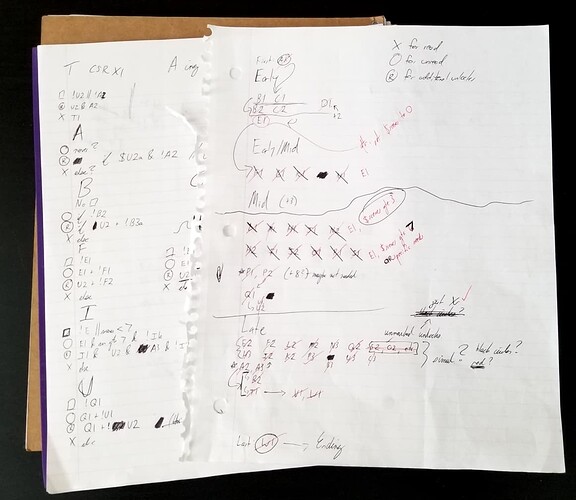

Initially this concept was going to be more, let’s say, heavy-handed. More explicit, with four+ versions of each scene involving revisions, removals, and additions of commentary from January as he gradually shook off the coma of grief and refashioned the telling of each scene to better suit his new sense of self.

For various reasons: no. This plan was not only logistically unsound, but also narratively questionable because January did not want to speak for most of the story; he certainly did not want to add cutesy notes to the detritus of his life. So I aimed to unfold the concept in a more natural way, with descriptions progressing from abstracted, painfully detailed and impersonal landscapes, to a more natural flow of action and commentary, to casual cussing and chattiness with the cat, and finally to first-person POV.

Not that it is an entirely linear progression. The narrative—the narrator—the author—all of us argue constantly and intertextually with each other about what should be kept in the story, about what “should not or will not disappear.” Indeed, there were many times that I continued to work on the game only because I promised myself that I’d delete it all when I was done, once I had properly excised this from myself.

I finally managed to counter that argument with, “Well, but what if someone else benefits from it?” I find comfort in consuming media about suicide when I feel that way, and there’s a separate essay here about normalizing and validating mental health struggles, but let’s table that one for now. But knowing how I appreciate that kind of media myself, it seemed petty, if not outright unkind, to refuse to share January.

That particular arguments comes through, for example, in the post-POV-shift train scene. January relates how he peeled the dying woman off the frozen train and wrapped her in a tarp “just in case” she changes her mind, as he did. The woman is, by all accounts, a half-corpse already and actively being devoured by an omen of death, but until you are sitting there feeling yourself die, you don’t know, I promise you, you don’t know whether you will change your mind. And far be it from him to decide for her—so here is the tarp, here is the story. Do with it what you will.

This concept also crystallizes in the final pre-POV-shift scene and the POV shift itself. As January falls ill with fever, he has a nightmarish remembrance from his childhood, opening with, “In the story he told himself about his life, death found him one night…” It’s one of the more inelegant phrases in the game, in the story he told himself about his life, but it’s exactly how it needed to be said. Every scene that has been presented to the reader is part of the story that January tells himself about his life. What you read was not his life. It was not even a factual attempt to recount his life; it is only the version(s) of the story that he chooses to tell himself.

This is critical, both to the reader and to January, and he tries to stress to us the fictionality of his account, many times, in many ways. He says that he cannot have slept for multiple days after the fever and the dream of drinking from the bowl of stars with Cat; he cannot have survived his initial suicide attempt in the parking lot; he should not have heard gunshots by the sisters’ house without glimpsing his pursuer or attracting zombies; he should have smelled the hanged man rotting; he should have noticed the presence of the little girl in the dogtrot house sooner, or she should’ve already been dead. And of course, he should have killed himself after they died. (And probably a cat shouldn’t be able to speak to him or understand him.)

Guilt and grief contribute to the instability of his account, but they don’t fully explain it. I do not want to pitch this as an unreliable narrator whose memories are wracked by trauma—quite the opposite. Rather than treating memories as sacred truths that should (or even could) be accurate, memories in January are tools of self-examination, things to be laid out and sifted through in an effort to process trauma. If the memories need to be reworked, details fudged, inconsistencies introduced, in order to make them fit better into his new self, all the better. There’s no one left alive to tell him that he’s remembering things wrong anyway.

(Sidenote: as someone who tends toward SDAM, I have a pretty irreverent view of memories. And I know that the memories I do have are factually inaccurate. I know this because I transitioned genders in adulthood, and yet all my childhood memories have been revised to fit my real gender, not the one I mistakenly happened to be as a child. In my memories, people always call me by the right name, even though that name didn’t exist twenty years ago.)

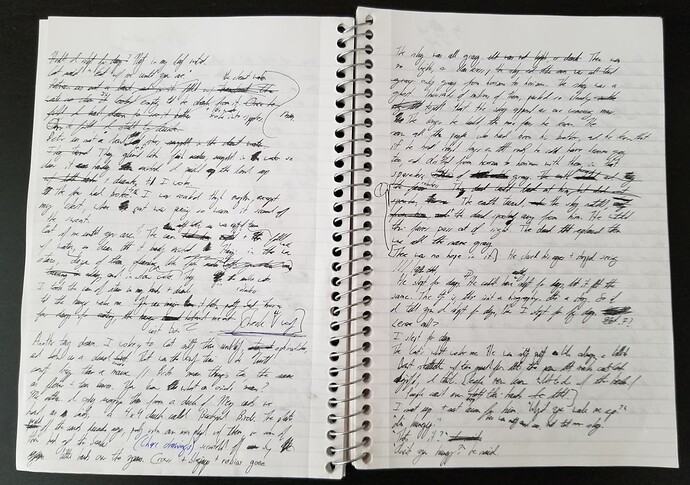

I want to highlight one more example of revisionary self-history in January that does not involve the POV shift. In the second scene of the game, in which January explores the dogtrot house, he describes the pain of his bruised ankle thus: “He breathed through the red. He imagined the bruise oozing through his sock like an open wound, dyeing the wool a deep, mashed, mulberry purple.”

Many months later, after January mercy-kills the hanged man, he describes the scene thus: “Red spilled from its neck. Pure blood red, not bilious or spoilt-black. From the collar of his shirt up to his chin, the man’s neck was mashed mulberry with deep bruises, and these must have continued into his face, but he could not see the face now and did not want to remember.”

To the reader, chronologically the ankle description comes first. But this is a narrative illusion. Everything in the game has already happened by the time the first scene loads. Thus, when we read the earliest scenes, we have to view them through the lens of the later ones—that is, January himself views his earlier memories through the lens of later events, as all humans do. To be specific, when January tries to think of how to describe his bruised ankle, his mind twitches back to the morbid sight of the hanged man’s throat (that he “did not want to remember” but that insists on being remembered anyway), and he uses that real event as a blueprint to imagine how his pain might appear.

A couple reviewers asked why anyone would bother to read the scenes out of order. I think this is the heart of the answer—because in January’s mind, the scenes do not proceed in order of chronology, they proceed in order of random association, just as you might remember a pair of birthday parties from when you were twenty and when you were twelve. The memories/scenes float together in a pool of associations. They gossip and converse with each other, stealing descriptions, reusing phrases, imprinting later images on earlier events, and referencing later events that the reader hasn’t experienced yet, although January has. Accessing them out of order opens the door to serendipitous connections between descriptions and better reflects the sensation of remembrance, I think—but as we’ve covered, I have a pretty weird memory system, so take that with a grain of salt.

I swear we are almost done with this section. LAST THING, I do want to address the POV shift directly. There is something very me about writing a story obsessed with agency while refusing to give the reader any. Sorry! But this goes back to the fact that January is telling himself this story. He is not telling it to you, you are not a character or an actor here, and so your agency is largely non-existent and unimportant. What matters is January waking up, re-becoming the protagonist of his own story, and eventually claiming ownership of it via the POV shift. I think this is the most obvious part of the game to grasp, so I won’t dwell on it any longer. ![]()

Or will I. (Yes, I wrote this section at 1:45am, how can you tell.)

Level Three

So we have the basic plot, we have the meta plot, and now we have… let’s call it, the personal plot, as the third layer of this shitcake. We are now stepping completely outside the narrative/the narrator and into my little brain.

Earlier I mentioned that I was researching how people use stories to cope, especially in the context of illness. Let us use “illness” very broadly to mean “disruptive health event,” anything from a severe injury to the development of a disability to a cancer diagnosis to mental health issues to chronic pain conditions to et cetera. In short, something that fucks you up.

Let us now imagine that many of the bad things that happened to me can be counted as “illness” and that they did fuck me up. Finally, let us allow the author to project their own grief and recovery process onto the two previous levels of plot. Et voila, we have a personal disability plot hiding in the game the whole time.

I don’t want to say too much about this, because one, it is quite personal, two, I don’t want it to affect other people’s readings of January–I don’t want to impose this as the “right” reading, and three, there’s so much overlap between this and the previous section that not much more needs to be said. We are still dealing with a life disruption, a loss of sense of self, an adriftness, a feeling of one’s life traveling on without you, of things Happening to You, a painful self-examination and reconstruction of a new self, and finally an ascent to some kind of agency.

The one thing I do want to highlight in terms of an illness/disability reading is the motif of eating that runs throughout January. Healthy folks may not immediately connect eating to illness, but boy howdy, are they intertwined. Eating is a nightmare for almost any kind of severe health condition. For example: you get the nausea and vomiting from chemo, you get the constipation from pain meds, you get your body trying to self-destruct via diabetes or celiac if you eat this or don’t eat it or eat too much or too little, you get a ravenous appetite from the mood swings, you get your appetite killed by stimulants, you are spitting up acid, you are shitting liquid, your fork won’t stop shaking, and you can’t get the food to your mouth. And so on.

Eating is such a fascinating, multi-valent concept in fiction. In this game alone, it encompasses the zombies’ unrelenting, deranged voraciousness and the tender little sight of January choking down kibble so that Cat feels safe enough to eat with him and the anxious morbidity of January insisting that Cat eat him after he dies. Which is to say, there are so many ways to read the concept of eating, but I’ll limit myself to commenting on it from this angle.

The first several scenes frame food within frustration: it is a necessity (January forces down the kibble in the dogtrot house, thinking of it strictly as “sustenance”), it is a repulsion (the charred meat in the train scene, mostly likely human flesh; the guilty dwelling on meat after the bird dream), and it is a thing-to-be-earned (the mangy cat doesn’t deserve kibble, January remarks, but we get the sense that maybe January doesn’t feel like he deserves it either). Ultimately, food and eating are symptoms of being alive, and that is anathema to January in the early game. Each meal forces him to recognize how hard he is working to stay alive despite the feeling that he ought to be dead. It’s a slap in the face.

In the mid-game, eating/surviving becomes something more rote, still unpleasant but not as guilt-wrought. January eats alongside Cat because that’s what they do. After Cat tries to feed him an oriole when he’s constipated and skipping meals, January later tries to return the favor by luring in a whole flock of birds for sick Cat to hunt. (Is it notable that both of their avian attempts to feed each other are failures?)

Of course eating/surviving/being alive also runs the risk of being dead, as highlighted by the scene where Cat seems on the cusp of death after eating some plant he shouldn’t have. While pleading with Cat, January asks what he’s supposed to do with all the food he scavenged for Cat—what is he supposed to do with all this effort at being alive, if it just comes to this again?

And the thing is, it will always come to this. All the living in the world will always come to death. This is the heart of January’s own near-death scene, in the next month, when he sees a gray sky full of ghosts and declares “there was no hope in it.” There’s no particular sunburst of revelation after the fever dream, just a realization that he’s still hungry and still alive and that Cat will sit and wait until January’s ready to eat with him.

(Ah, the bowl of stars that he drinks from. That image/phrase is a direct rip from a very famous horror novel, and if anyone can name it, one free cat cuddle to you! [Must supply your own cat.])

I could pick at more details, but you get the gist here. A last note on illness/disability: I didn’t really get into the horror genre until I was unwell, and then I used horror movies both to escape from pain and to realize the pain, to watch someone else suffer and nod from my seat and say, That’s it! That’s it, that’s what’s inside me. You all can see it too, now. Apocalyptic settings are a bit different, but related—it’s not so much about the pain and fear made manifest as the loss. Becoming disabled is very much a private apocalypse. Swaths of society are lost to you. You cannot go there; you cannot participate in the thing; you cannot create what you used to. Please don’t take this as an invitation to debate inclusivity measures—just believe me for a second when I say some doors are closed, and there is nothing you can do but accept it and find a new door to open.

January doesn’t spend very much time lamenting what’s been lost, not in tangible terms like missing pizza or electricity. In fact, he regularly refuses to engage with the remaining shreds of civilization. He’s not comfortable staying inside the apartment of the woman with the painted nails, nor entering the cottage in the garden, and though he makes some allusions to camping in houses from time to time, this is never shown on screen. He only tells us about sleeping outside in his tent. So, we might say that he copes with the apocalyptic loss of society by rejecting any desire to reconstruct it. Instead he forms his own routines, as many disabled people do.

A favorite scene for many reviewers was a short one in which January gives new names to the flowers he doesn’t recognize. Loss perfuses this scene, but so does freedom—the realization that you can shed what was lost and reconfigure what still exists. The flower scene presents a tidy bow, I think, on top of the messy package that is illness, grief, trauma, and autobiographical reality rewritten.

Thanks

Finally, some thanks. Thanks to Sjoerd for teaching me how to use TweeGo (it’s still scary and arcane), huge huge thanks to Eli for working with me on producing the art for the game, thanks to all who read January, and thanks to those who attempted to read it and said “absolutely fucking not” for their own well-being.

I’m still completely gobsmacked about placing in the top ten, and I really appreciate all the feedback that folks have given me, both publicly and privately. Take care of yourselves, everybody, and if you ever want to talk through stuff, feel free to reach out. <3