I think it’s great the organizers are dealing with this issue. First of all, let me emphasize that I’m thrilled that IF and the IF community is growing, and that IFComp is such a popular event. I very much enjoy the diversity of entries in recent years, both in terms of genre and form. I love the feeling of picking the next game from the list, and having no idea about what’s going to happen, except that it will probably be original, enjoyable, and good—possibly great. And that’s another thing: This is not a debate about quality vs. quantity, because the quality of most comp entries is actually very high.

But I think we do have a problem. If we want the IF scene (on this forum and elsewhere) to be a living, thriving community, then we have to be able to have interesting discussions about a common set of topics. We don’t have to agree on things (heaven forbid), but we need some kind of common language, a set of ideas and experiences that we can talk about. IFComp, of course, is the single biggest event on the IF calendar. Each October, people from all over the planet emerge from their hiding places and come together to join the fun. Forum activity increases, people write lengthy blog posts and reviews. But IFComp needs to be a shared experience.

With over 80 entries, most judges will only have time to look at a small subset. The official word is that you only have to play a minimum of five games to be a judge. But here’s the thing: If you play five random games, and I play five random games, then we didn’t have a shared experience that we can talk about afterwards. In fact, with 70% probability, our samples didn’t have a single game in common—let alone two, so that we could talk meaningfully about relative merits.

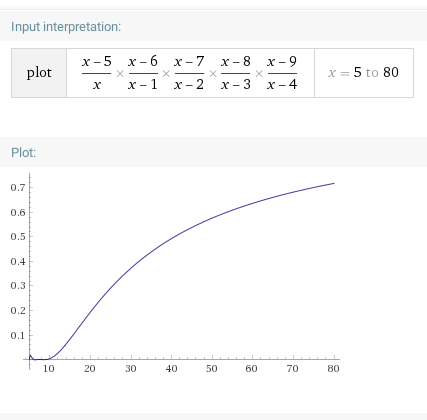

Here, let me plot that:

The X-axis represents the number of comp entries, and the Y-axis represents the probability that a given pair of judges—each picking five games at random—do not share the experience of even a single game. Of course, the other parameter to tweak is the recommended number of games. Five is clearly intended as a hook, to get people to start playing instead of just being overwhelmed and giving up. The unspoken hope is that people will actually play more than five games, and many presumably do. But in a competition with, say, 20 entries, I think many judges would actually set their minds on rating every single game. And most of them would follow through on that ambition.

The point I’m making here is emphatically not about fairness. A competition with non-overlapping samples can still be fair, as long as each judge is selecting entries at random, perhaps by following their personalized shuffle order. No, this is about building a community where people can participate in meaningful discussions, grounded in shared experiences.

Now, some suggestions. Like I said at the beginning, I don’t think we should place limits on the kinds of stories that people can submit. But perhaps we could place a limit on how many stories a person can (co-)author per year? Now, I know this would have excluded several excellent entries from past years, but those entries could have been released in other competitions, or saved (perhaps even refined further) for another year—for the greater cause of reducing the number of entries in IFComp.

Another idea is to introduce a separate side-competition, sort of like the back garden of Spring Thing, where the rules are a little bit different. In particular, the two-hour rule could be relaxed, the deadline could be a week later, and the judging period could be extended. If we then dedicate a fixed proportion of the colossal fund cash prize to this sub-event, then we create an incentive for authors to select the least popular category. The original 1st of October event would probably see a larger crowd, and therefore have more entries, but as a consequence it would be easier to earn a top spot in the back garden, and get a larger cash prize. And when the deadline for the October event is getting uncomfortably close and you still haven’t found that crashing bug, you’ll no longer have to choose between submitting a buggy game this year or a working game next year—you’ll be able to submit a working game next week (albeit probably to a smaller audience). And that’s a win-win for authors and judges.