Disclaimer

I’m gonna talk a lot about my game because I feel like it’s been an interesting development arc. I know it’ll come across as indulgent. That’s probably not wrong!

On a similar topic, as an author all of the following is just what the piece means to me. Your experiences may differ and that’s fine. A piece of IF work only happens between an author and a player.

We put our works out into the world and whatever life they find, that’s great.

Statistics for nerds

Development period: July 2022 – IF Comp

Programming languages: Twine and TADS 3

Testers: 6

IF Comp Reviews: 13

Game Cruelty Scale: Merciful

Introduction (Twine): 40 Passages total, 32 story passages, 5,425 words, 455 lines of code, 1 file

Main game (TADS 3): 9,875 lines of code, 53 files (plus 4 modules)

- 6,290 Objects, 600 Things, 11 Actors, 30 Rooms, 10 ComplexContainers

- 182 conversation/consultation/interactivity topics

- ~62,640 words of my text

Finale (Twine): 177 passages total, 169 story passages, 28,658 words, 2056 lines of code, 20 files

The above statistics are reported by tweego for the Twine games. TADS 3 statistics were either gathered from forEachInstance loops, or a delta with a minimal TADS 3 game. Take the numbers with a grain of salt since I haven’t definitely filtered out all library objects, or debug text.

The Story Before

The last time I entered IF Comp was 18 years ago, in 2005. I wrote a game called Mix Tape which was a TADS 3 game merging the story of Ben Folds Five’s Smoke and the book/movie High Fidelity.

It got equal 18th place out of 36 entries. Reviews weren’t great. Some were “meh”, others scathing. In my judgement, the game was terribly unfinished, unpolished and immature. As a piece of Interactive Fiction, the Interactivity was woefully underdone and the Fiction was problematic. It was written like static fiction with interactivity getting in the way. It was a self-inflicted failure.

On the other hand, it got nominated for Best Writing in the 2005 XYZZY Awards.

For reasons I don’t quite understand now but can only guess, I abandoned the IF community in deep embarrassment, archiving all my project ideas. Over the decades, I did some minor betatesting for people, but I barely kept in touch with the community.

Hand Me Down

My understanding of the game is that it is an interactive fiction game about creativity, fatherhood and the passage of time.

Software engineer Miles Walker has an idea to make a game for his daughter, Ruby. All he knows is interactive fiction, so that’s what he sets out to make: a puzzle-parser romp called A Very Important Date. Fatherhood and life is harder than he expected, and he keeps not being able to complete the project for his daughter. It however remains a rock for him to cling to as they all get older. He is close to abandoning the project until he gets a diagnosis of potentially terminal pancreatic cancer. During the treatment he has a lot of extra time to write and think. With the unexpected help of Ruby’s partner, James, he completes the game and gives it to her before major surgery.

You play as Ruby, learning about the game and then playing it. Although you want to know more about your dad’s condition, he wants to spend what might be his last hours, talking about the game and life.

My inspiration for the core story were news reports of fathers who had secretly made giant Minecraft cities for their kids to play in; sons being able to play Forza against their dead father as a ghost car; and Jason Rohrer’s Chain World.

I have two children now: a five-year old daughter and a one-year old boy. I had imagined a similar starry-eyed project for my first child before she was born. I was just coming to peace with Mix Tape and considered something like what Miles creates.

I did start on the project, scratching out some very minimal rooms in TADS 3 and building the beginnings of a Minecraft world whilst watching many a TV series. But the reality of parenting and life overtook the romantic idea, so I left it in the attic of my mind.

For many years my primary worry — other than being a good father/husband/worker — was finishing projects. I had a long list of unfinished projects. It was distressing to me that I spent so many years bouncing between creative projects and had produced (as far as the world could see) nothing except a fairly meh IF Comp game in 2005. Something needed to change.

Originally Hand Me Down was designed as a memento of a father left for his child. I had plans to put it in IF Comp 2020. But it just wasn’t finding traction.

Development

About a month before Baby 2.0, the project began to speak to me again. Even though it wasn’t my favourite idea at the time, I decided to take Hand Me Down as my primary project to tackle a number of problems simultaneously:

- Thinking about fatherhood

- Returning to the fantastic IF community

- Complete a project or die trying.

I basically handcuffed myself to the bulldozer and set it in motion. As with everyone who didn’t take up sourdough bread baking during the pandemic, I wrote a monthly Substack newsletter. It is about my creative process as a way to discuss Hand Me Down and be accountable, at least to the few friends of mine that read the posts. I was going to do this, dammit.

I have to acknowledge the deep help that @mathbrush provided to my project. Early on I pitched the idea to him, and he helpfully framed it within the larger IF corpus, pointed out prior art and encouraged me to try it. This gave me the confidence to continue with the project. He was one of my great cadre of testers.

(I must also acknowledge a nameless escape room designer who I pitched original escape room aspects of the game to, and he thought the idea was awful. In a way he was were right, and wrong. The pushback there was useful.)

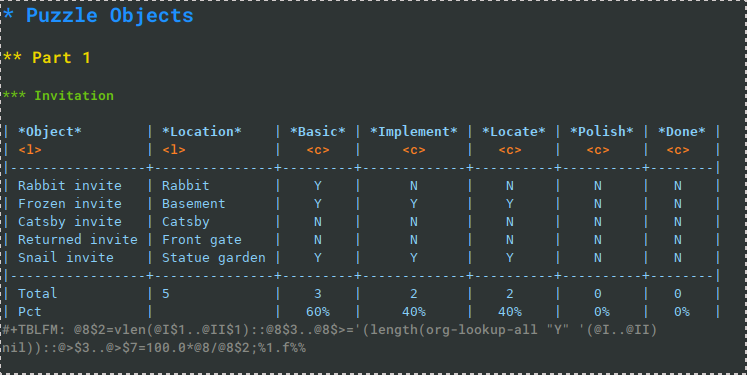

I enlisted a good friend, Mike, to be my accountability buddy. He does game design as well, but not IF. Every few weeks once the project was getting serious, we’d have coffee and discuss the game. He was a good sounding board, and kept me honest with a brutal efficiency. Where I might convince myself that I had a definite plan, “for sure”, he made me make it specific with actual deadlines and scope and numbers. I kept an array of tables listing all the rooms and puzzles, and where they were up to development-wise.

Throughout 2023 I took a number of weeks off work. Some of that was stymied by sick kids or [crazy hand gestures] life. Most nights I was working on the game for a few hours after the kids went to bed. I didn’t watch much TV or play many games. Near the end of development, my wife was graciously taking the kids away for much of a Sunday to give me a little more development time.

You can see I owe a lot of people a lot of gratitude.

I worked hard, harder than I ever had on a project before. I wrote the introduction three times, each time in a session or two. The main game was a tremendous amount of work, and was trimmed significantly from the original idea (more on that later).

In the last 30 days before the Comp, I wrote the finale and a large, sophisticated piece of parser fiction that I ended up removing from the game. The testers didn’t get much chance to play the entire game through, but did hammer on the main game.

Title

The project has always been called Hand Me Down, although I couldn’t decide on hyphenation or not for the longest time. I like that it is a common, evocative phrase with a literal reading of handing oneself down. We hand down our products of life to those that follow, whether those products are our children, or our creative projects. We hope a little bit of us survives the transition.

I never really liked the title of the game-within-the-game, A Very Important Date. It’s intended to capture the main idea of the game, and evoke Alice in Wonderland. I wish there was a variant on the main title I could have used, to tie everything together more. The name was a Miles decision, though.

Searching for Structure

Throughout the project I always had the idea of the framing story, the TADS 3 inner game and then some sort of ending. But I had all sorts of artsy (and, frankly, dumb) ideas for the non-parser bits.

One conception I had was a five-part structure:

- An introductory framing story.

- The mansion exploration

- An escape room plot twist

- A weird walk through IF in which each room was a museum memorial to the father, kinda like a small, sad Cragne Manor memorial for someone in the IF community.

- Some sort of denouement (read in the same way as in a mathematical proof: “…Then a miracle occurs”)

Originally the father was dead before the start of the story. Your step-brother had James’ role of giving you the game from your father. The step-brother himself was the product of some extremely tricky timeline and family arrangements, rivalling Back to the Future but without time-travel. The mother was absent but there was a whole “two families” thing going on.

This was altogether too much. The sadness of the father’s death kept the entire game in a shadow, and robbed him of any direct character. The step-brother was weird and too complicated. It was all too complicated.

Talking to Mike, we brought it back to the core idea: “Hand Me Down”. With the step-brother as intermediary, it was kinda “Hand Me Aside”. If the father is handing down his legacy, it should be in that manner. The idea of a father handing his history down, and handing his daughter to her partner was poignant. I worried it might be interpreted as misogynistic, but I really mean to focus on that sadness that one day a father has to accept he won’t be there to look after his children, and it’s important that he find someone to take his place in that inevitable circumstance.

So the step-brother (Will) became Ruby’s partner (Will) who was renamed to James because Will and Miles seemed destined to confuse people. I jettisoned entirely the memorial for being far too weird and artsy.

Up until the end of August 2023 I had the escape room portion. I wrote most of it. The basic idea is a lived-in escape room where you are a freedom fighter against a fascist regime (which actually was a running gag about teenager rebellion against parental rules). The sky had an oppressive dirigible barking out orders like, “We are an open-minded authority. No discussion!” or “We want YOU to clean your room”.

It’s got some great writing shedding further light on the characters, and much more intricate escape-room-style puzzles. But it was again too much.

And following the comp reviews, even cutting these huge swathes of content out wasn’t enough to comfortably fit the game within the two-hour review box. I don’t know whether to reinstate it in the post-Comp version.

Midway through 2023 I was driving to work and had an “Aha” moment: Miles didn’t have to die at the start. Having him be alive and able to interact with Ruby made so much more sense. It offered better story, clarity, characters… I had even toyed with removing the threat of terminal illness, but the long-term inevitability of death, and the finale’s short-term deadline made for a better story and thematic resonance. Sad, though.

Overall Structure

Once I had a better idea of the piece, I structured it intentionally in light of the themes of fatherhood and interactive fiction.

As a timeline/homage to IF, the three piece are:

- Very basic choose-your-own adventure with close to no real interactivity

- Old-school parser romp in TADS 3.

- Modern school Twine story based on storylets.

As a remark on structure as a child growing up:

- Basically no consequential choices.

- Freedom in a boxed playground with only consequences you choose to take on.

- True freedom, but with consequences visible and invisible, and coming to grips with mortality.

I had wanted to have choices percolate through the three games, but that was a technical and design difficulty that I couldn’t overcome in time to my satisfaction. Twine anchored the games to the web, but TADS 3’s web story is complicated and not as good as you might hope, despite dedicated work from the community.

Main Game Structure

The three-required-pieces puzzle for the main game was always part of the design, but I originally had an arbitrary number of puzzles. I had close to a dozen ideas for shareables based on “What can you share? A meal, a secret, a song, a discovery…”

I had a number of costume designs, but once they started to reflect the five main characters (Ruby, Miles the dad, Kim the mum, James the partner, and the grandfather) I leaned into that structure.

There are five costumes corresponding to these characters: James is The Archaeologist, the ex-navy grandfather is The Captain, the dad is the “Cool” guy, the mum is The Monster, and Ruby is the Powerful Princess.

The five invites very roughly correspond as well: Grumpy Catsby is Mum, Rabbit is James, the returned invite is the grandfather, Snail is Dad, and Ruby’s invitation was on ice, like the game is for Ruby.

The shareables weren’t well-aligned with the characters, although the board game pieces correspond to the colour themes of the characters (Ruby red of course, Dad green, Mum purple, James yellow and grandfather blue) and the board game piece descriptions relate to the character. Plus they are found on a statue in the statue garden that symbolises the character. Phew!

The “memento to share” was really just me using a cool plane lockbox I made. I gave two versions of the unlock code in the game because I thought it was too well hidden, which confused people.

The grandfather’s story came in late and became a nice way to fill out the rooms a little more. It was very awkward that it’s done in the abstract though.

The picnic was just fun and cheesy. After a near-riot from my testers, I had to include the scratch-and-sniff page from the cheese encyclopaedia because I had idly mentioned it had one.

The scientific discovery was my attempt at a “proper puzzle”. I can’t decide if I liked it or not.

I stole the hidden notes idea from another game I started writing (Convolution) and every video game ever. The canon for this was that Miles keeps the game files open all the time to make sure he keeps working on the game. He reflexively writes diary entries alongside the real code. No-one reads code comments. Not even the compiler, right?

James is a digital archaeologist. His hidden influence on the game is to curate those diary entries and hide them in the game. This is the in-game reason for them being in weird places and being substantially more difficult to find. It’s not mentioned in the game, but in my head, James coerced Miles into their inclusion. James’ role is seemingly subdued across the three mini-games, but his story is complicated; ethically and narratively.

Finale structure

The finale is structured around a locus: you keep returning to the same conversational hub, but each time choices you’ve made have unlocked or locked out conversation paths. As you chat more, more opens up, but you run towards the deadline.

Time passes depending on story beats. I had thought of randomising it, but that was distracting and may have lead people to undo and redo to cheese out more time. There’s not a lot of variance to the section timings, but there is some.

The storylet design required a lot of technical work to have the options unfold in a clean way. It wasn’t as clean as I’d like it, but I was working around Harlowe there.

I enjoyed my execution of the little scare of your mum interrupting the emotional conversation with a video chat. This took a bit of Twine and CSS magic, and was a nice way to bring the mum back into the story. I think it had mixed results.

Apart from mechanical stuff like recording the time, the game tracks 27 variables like which costume you liked, whether Miles, Ruby or James are meeting their goals, and dumb things like your dad’s craving for chicken nuggets. Variables tracking character mood and whether they are meeting their goals are the biggest effects on the code, and are boiled down to two scores that decides the ending. Most of these tracked variables do very little.

There are four possible endings, each similar but different. They mostly dictate the story of what happens with each parent, which is weird given the arrow of time implicit in the concept of “Hand Me Down”. I didn’t want an overly sad ending as that felt like an extra twist of the knife I had been twisting for two hours. Nor did I want a shiny happy ending, which might have betrayed the stakes beforehand. I liked the middle ground.

Writing

Midway through writing Hand Me Down I realised I had a peculiar artifact on my hands. Usually fiction gets to do its thing and then is done. Reviews and discussions are outside of the fiction. But Hand Me Down could comment on itself inside and outside of itself, depending on your viewpoint. The finale could analyze the main game, reinforcing or skewering it. The characters in the finale are different to the characters in the main game.

I’m a big fan of Charlie Kaufman, so this tickled me immensely, but is worryingly artsy.

I did realise myself that it gave me an opportunity to paper over all of the game’s shortcomings as Miles’ fault. That’d be easy to do, but I chose the honorable route. All the bugs and bad ideas are mine. The un-evenness in tone in parts of the main game was at times intentional, to signify the shifting foundations in Miles’ project over time.

I wanted to keep an extremely tight cast. In other projects my cast explodes, and I wanted to write differently. My timeline notes include a husband for Kim (Art), and Miles dates two different women after Kim (Kylie and Quinn).

The grandmother was an oversight until late in development. Her story was sad but important. After Malcolm and Dora move young Miles out to the country, Dora is killed in a car crash. This small story gave a better grounding to the house itself, and suggested reasons while Miles grew up how he did.

As I mentioned before, James is an interesting character. His main character note is the digital archaeology and his full name James Evans is a reference to Arthur Evans, the famous archaeologist who was controversial for doing a significant amount of reconstruction of the Minoan palace of Knossos. James is always signalled by his “deep amber eyes”. The Rabbit has his eyes, and a character from the escape room (Captain Evans) also has them.

James’ influence is all over the main game, and I am ambiguous as to whether this is a good thing or not. His role in the finale is moderator, trying to bring you and your dad together.

Ruby is fundamentally an angry character, as a strength and a weakness. Amidst all the drama, I had to make sure she wasn’t too emotional. I pulled the anger back a lot, but you can still see it. Revisions 1 and 2 of the introduction suffered from an overly-emotional Ruby.

Ruby in the main game is the father’s platonic idea of Ruby. She’s not angry, although references to it were snuck in (the tantrum tiara).

Kim is roughly the villain but I wanted her to be empathetic. Her story is that she dealt with post-partum issues poorly (not helped by Miles). She focussed on a worry that she hadn’t lived her young life enough, and didn’t want to be tied down as a mother. She still was a mother to Ruby, but on her own terms. She left Miles because of all this. Miles tries to be very understanding, despite being deeply hurt and abandoned by it.

It’s hard to say if Ruby’s anger is parallel or orthogonal to her mother’s plight.

The grandfather’s main story is wanting to hand the new family manor to Miles, but Miles doesn’t want it. He doesn’t want his childhood for his child. He wants something different, even if that comes at a great cost. This story is spelled out explicitly in a note in the hidden safe. If you need a hint for the safe: https://xkcd.com/1688/large/

As expected, Miles’ story is reflections and mutations of my own thoughts about family, interactive fiction and creativity, although he is very different to me. I use the game to comment on him, and vice versa. His obsession with completing the game long after it should have been abandoned is a comment on my struggles with projects. His main arc is finishing a game, despite the costs. He loses sight of the reason for the game, and becomes fixated on the mechanics of finishing it for a particular birthday. Terminal illness jolts him out of that mental trammel. I dedicated a lot of time and energy to Hand Me Down, but intend to do differently to Miles. As a point of fact, I finished my game in a year and he was still going after decades.

That said, some of my own tiredness influenced the writing and completeness of implementation, especially on the upper floor. I was very keen to avoid the disaster of Mix Tape, but still missed the mark a little.

I spent a lot of time trying to have a balance of fun and emotion, Sock vs Buskin, Thalia vs Melpomene. I did, however, have a better feeling for interactivity than Mix Tape, and tried to at least provide the opportunity for a player to find something useful.

Did I mention this was the first time I had ever written a Twine game? I think I did okay in that regard.

Reception

My five-year old daughter gave me my first review. She had understood that I worked studiously on the game for the past year. She wanted to play it. I avoided the framing story and thought I could walk her through the first few rooms and have a fun chat with the rabbit. My daughter got increasingly upset and finally blurted out, “This isn’t a game! It’s just writing!”

No other reviewer skewered me so neatly.

Before the Comp went live, I stressed about reviews. I had thought of a way to download reviews, pass them through the useful idiot that is ChatGPT, as ablative armour. I never did it, but no need.

The reviews have been touching, thoughtful and generous. I’m in awe at the dedication from the people in the forum reviewing so many games with such care, courage and creativity.

Overall I feel the reviews have been pretty positive, but from the general buzz, Hand Me Down isn’t a top tier finisher. Fair enough, though. The games in this comp are incredible.

Teasing it out more, my expectations are that it’ll come middle of the pack again:

- The three mini-game structure is a friction point

- Having a substantial parser game is a friction point

- Being quite long is a friction point

- Having content warnings of terminal illness and divorce… Oh you better believe that’s a friction point.

I feel like I have a pretty dense, but not uniformly so, implementation of objects in the parser game. There’s likely enough splinters, rough edges, and weak ideas to make a judge sad. I tried really, really hard to smooth the game for everyone via structure and design, but there’s a lot of edges in 30 rooms and two separate stories.

I felt like overall my writing was the best I’ve written in years. It appeared that the escape room note in the umbrella never failed to land its heavy punch. People laughed at some of my big comedic gambles (the snail puzzle and the compost puzzle). I feel like the Twine and TADS 3 parts have strong, distinct voices. The “bottle episode” structure of the finale turns out to be really hard to write in, but I feel I did well.

I think I did Good Work™, but it’s definitely not a game for everyone. The Art I attempted elevated and undermined the work at different points for different people. And that’s okay.

The implementation isn’t as nice as I’d like it, but it’s a significant improvement over Mix Tape.

Random Musings

- My testers were absolutely amazing. Thorough, patient and kind (even if they did throw the model plane into the rabbit’s face a lot).

- I also learned that some players walk into a new room and just

GET ALLandX ALL. My poor designs were undone in the face of such productivity.

- I also learned that some players walk into a new room and just

- Thanks to @alexispurslane for taking over the Emacs plugin for TADS 3. She vastly improved it from my horrible borrowed code, and took away a potential yak-shaving avenue so I could stay focussed.

- I made a special email address for the game to get feedback or bug reports. Not a single soul emailed it. I hear this is common. I did get a lot of messages on the forum.

- I commissioned a fantastic Australian artist for the title art. It was a great experience, and I was happy with the results. I always love working with artists. No-one said anything about the picture, though.

- I used Midjourney for some minor art in the Twine sections. I thought they were fine, not deeply inspiring but had the right number of fingers and did the job they had to do. It’s basically clip-art with control. But they were glass shards in the eye for some people. I’m very glad I didn’t go through with one of my tester’s suggestions to accompany every room in the main game with an AI art image.

- I freaked out hearing that people hated timed text in Twine, especially since my finale had exactly that. I thought I did it well, and no-one has yet commented. Bullet dodged?

- I named Ruby very early on and didn’t tell anyone. My daughter independently had an imaginary friend for a while called Ruby that got her in trouble from time to time. Freaky.

- The telescope puzzle has a basis in actual astronomy, which I promptly threw out the window for a cipher puzzle. I like the final answer though.

- The Catsby, telescope and ice box puzzles were all complicated pains in the neck for different reasons.

- I think I uncovered some actual TADS 3 bugs (

PICK UP NOTEthenREAD ITcan choose some other item that shares ambiguous vocab). Argh! - I wondered if I failed the Bechdel test. Mother and daughter talk, but invariably mention the dad. The snail is hermaphrodite, and talks to the negative-space-character of the gardener, but I’m not a Bechdel legal scholar. I tried, though.

- My meagre claim to boatiness quotients (boatients) is the Naval captain theme for the grandfather. I missed a trick not including a ship in a bottle. I did make an intentional, tactical “boat/ship” troll on any naval adept.

- Don’t ever put computers in a game. That’s putting errors inside errors. Errors squared.

- I made my own system of Topics so that interacting with computers was like a special conversation. That worked well in some regards, but catastrophically in others.

- I put a railfence cipher on a split-rail fence. It’s not a significant or meaningful puzzle, but is a pleasant surprise to the solver. It was intended to subvert expectations a little, and find yet another way to bring character into the game.

- There is a reference to Mix Tape in the letter box. I just had to.

- I can’t believe I was the first person in IF to have a cat character called “The Great Catsby”. What a steal!

Where to next

I’ve been given a lot of feedback on the game. Acting upon it would violate the “bug fixes” Comp rule. But I intend to do a post-Comp release smoothing out problems and enriching the manor a bit more. I haven’t decided whether to reinstate the Escape Room twist section, having thrown off the shackles of two-hour Comp limits. I also haven’t decided whether to commission proper art for the Twine bits.

I’m so glad to have completed a game and that game has touched a number of people. I’m keen to set it down and move onto something else, but it might hang around for a little bit longer, like kids who take the longest time to leave the nest.

Thanks to everyone who played or reviewed it. I won’t be able to make the livestream on Monday, but I’m cheering everyone on. I’m in awe of the superb work in this Comp and wish everyone the best. It was a great Comp to be a part of.

And thanks for reading all this. Feel free to message or email about the game.