7.- COMIC VS VIDEO ANIMATIONS

As I told before, this game embraces the paradigm of using comic vignettes instead of the usual videogame sprites animations, and the idea is doing it as the main system to communicate with the player and doing it without using text.

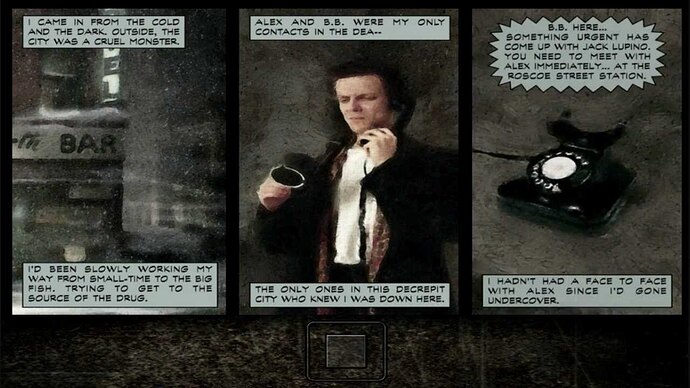

I can think in other mainstream video games using a comic medium as a substitute for the classic video cinematics for cutscenes, like Max Payne:

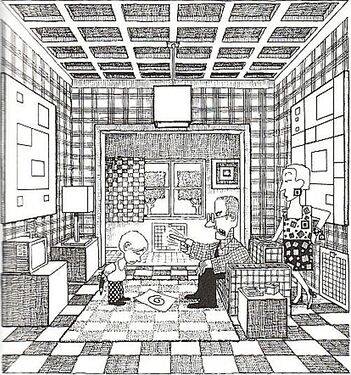

I can also think of another video game that goes further and uses comic also as the gameplay mechanic: “This is the police”, where sometimes there is a crime you must investigate, and you have “pictures” of the possible facts, and you must choose which ones were the real facts and the order in which all that happened. So, the comic is used there as an input to the system, in a very interesting way:

The vignettes for crime solving in “This is the police” don’t have text in them, although some text is added outside them to give context, like witness testimony of what they saw or heard.

The way “Gent Stickman vs Evil Meat Hand” uses comics is different, not using text at all, and being that it is the only way to communicate with the player. I think that was the hardest part of this game development.

One of the greatest artists doing this kind of communication, and a great inspiration for me, is the Argentinian comic creator “Quino”. His most known work is the “Mafalda” comic strip, but although I love it, his works I like the most are the one-page comics without text, some of them with only one vignette, like the one I use on itch.io comments to tell Dorian Passer how I felt about his game being disqualified from ParserComp 2022:

This talk about that kind of one-vignette “comic” style gives me the opportunity to make some clarifications about comic communication in “Gent Stickman vs Evil Meat Hand”.

Some authors, one of them with an excellent book about comics being a comic itself (Scott McCloud, “Understanding Comics”, 1993), consider that graphical works having only one vignette does not constitute a comic, because the comic works in the “gutter”, the “space” between vignettes, being the juxtaposition between them in the space that makes the brain work to build the story through “closure”.

This game has two kinds of comic communication:

The first one is in the locations themselves, each one being a vignette, without the frame around them to maximize the feeling of possible movements. They are side to side with other locations, left and right. But this is only true in the player’s mind. There’s no physical connection between them as they never appear side by side on the screen. This assumption (a right one) is made by the player that is taken to another location when he types left or right. So here, that gap between vignettes in a classic comic is filled with the player’s interaction. Of course, locations are virtually and logically connected, but they are not visually or physically connected as vignettes.

The second kind of vignettes are more recognizable as such, because they have a black frame around the drawings. Those are the images shown as a response to the player. The initial idea for the game was to put them one after another horizontally, keeping the older ones on the screen moving at the left side to make space for new ones as they appear, and losing older ones through the border of the screen when there are not enough spaces to show all of them at a time.

But I thought that this was visually less elegant, and that changing them to the final “slides” mode would still keep the comic concept, changing the classical space by time juxtaposition, without trying to be a “video” attempting to fool the eye with the retinal persistence of images, but just a kind of comic with “double page size vignettes” where you can only see one after you flip the page (or if you prefer, as one of those new “webcomics” ready to be read in a smartphone, with each vignette having the size of your screen).

And this removal of the classic interaction needed to move through vignettes or flip page is the other change from a standard comic, as here the vignettes are replaced in an automatic way and the only possible way to read them is to speed up their “slide”.

Using “comics” that way loses some of the narrative features of their language although we win some others:

-

We lose the ability of arranging vignettes in space the way we want as an expressive resource.

-

We can’t (or we decide not to) use different vignette sizes to change the narration rhythm, although some comics also do that because of the media they are in, like some newspaper comic strips.

-

We have control over the order in which vignettes are viewed and how long they are seen (we set the same time for everyone, but this could be something variable). We lose however the “peripheral vision” of the reader over the surrounding vignettes (and so, the surrounding “time” and facts), but we win the surprise effect when showing each new vignette (this one works especially well, I think, in the “Nadia Comăneci” moment jumping the pit). In a classic comic this surprise effect could be achieved by positioning the “surprise” vignette after a page flip, for example.

-

In the locations, the player can move through the “vignettes” (locations) of the comic depending on his decisions, inside the limits imposed by the game, making it in fact an “interactive” comic.

I’m not an expert in comics. I like them and have read some typical comic theory books (Eisner, McCloud, …), but I’m not an avid comic book reader but a casual one.

I like the idea of experimenting with the media, although perhaps I’m doing horrible things to it with this. I would love to know the opinion of people in this sector and know more about the use of Comic language in video games, especially “no words ones”. Superhero comics are not the kind I like, but I know that in the last times there some Marvel comics created under the collection title “'nuff said” (enough said), being a comic series without text. Perhaps this kind of communication without words is fashionable @.@