The English word for that is just “mystery”, like in the Eleusinian Mysteries. It’s just not a meaning that’s especially frequently encountered these days!

I totally agree. But the question was how the genre, by definition, could branch into “supernatural” and “riddle stories”. That was just an attempt of explaining how the supernatural part of the genre definition came about.

In Germany, I would say that if you told someone you were reading a "Mystery Novel ", most (if not all) would assume you meant something that has supernatural elements to it. Few would assume it was a detective or crime story.

And throw Columbo into the mix… ![]()

I think it’s possible to mistake general use of the term “mystery” in American English, which absolutely characterizes things and situations that are unknown, indeterminate, or otherwise beyond understanding, with a literary term that is by nature more technical. A ghost story would likely be quite “mysterious,” but it would probably not be an example of genre fiction generally referred to as a “mystery.”

A shopper browsing the “mystery” section of an American bookstore in hopes of finding tales of the supernatural would leave empty handed, unless they found what is widely understood as a mystery that, coincidentally, featured such elements. While these conversations always imply that categories are vague and hard to define, in reality, almost everyone knows which aisle to visit first when shopping for books.

There are obscure usages, as in Mike’s example or the equally specific and arcane use of “mystery play,” but but one may never encounter them on the street or, for instance, the daily news.

I speak only of American English, of course.

From a UK point of view, I’d sort of really regard a “mystery” and a “murder mystery” to be quite different genres of novels… with the former definitely having some undertones of the supernatural. On the other hand, something like “crime”, which is one of the definitions used by CASA, seems far too harsh… when compared to “mystery” or “murder mystery”… and evokes thoughts of bank raids or robberies, rather than quaint English whodunnits. It always feels very odd to tag such games as “crime”.

I notice that the Amazon book store goes for “Crime, Thrillers & Mystery” with additional sub-areas including Thrillers, British Detectives, Mystery, Police Procedurals, Spy Stories, Action & Adventure (!) and Psychological.

It’s true! British mystery is massive over here.

Would “murder mystery” be synonymous with “whodunnit”? - Where the point is to potentially guess the killer before the end?

Where a pure mystery might be just something like “Why is this cult accumulating all the bismuth that exists in the world?” or “What was all this ancient machinery designed to accomplish?”

Myst…Mystery ![]()

Genres are often best combined in a salsa… like how Knives Out sets up all the trappings of a whodunnit mystery then throws all that out in 30 minutes and transforms into a thriller howdunnit, then another mystery which was completely and fairly set up but misdirected boomerangs back in the third act.

I love how Knives Out is basically Chekhov’s Gun: The Movie

The mystery tag on IFdB currently has a bunch of murder mysteries, but one of the highest is Babel, which involves waking up with amnesia and trying to figure out what happened.

I always thought that was weird, since I consider that to just be basic sci-fi. People can use any classification they want, but if I’m searching for the Mystery genre, I’m generally looking for a game with investigation, interrogation, and clues. This is just my opinion, and not something I think everyone needs to agree with.

So far, it seems the majority expects some sort of crime, though with some exceptions such as e.g. a cat is gone missing and only at the end of the story will we know if it was a crime or something else has happened.

My own view was that if the plot is basically about something that is inexplicable until near the end, I see it as “Mystery”, independent of whether it is a crime or not. But if a game already has a genre and if most people expect some sort of crime, then it might feel misleading. But I like that Babel is labeled “Mystery” ![]()

It also made me think that it may depend of the topic (games, books, movies etc). Those who came up with the “official” genres on IFDB must have had some idea so the official genres do not overlap. I am aware that you can choose to use your own genres. I just notice that none of the official genres are crime. For instance, Ryan Veeder’s first hit “Taco Fiction” is labeled “Crime / humor”.

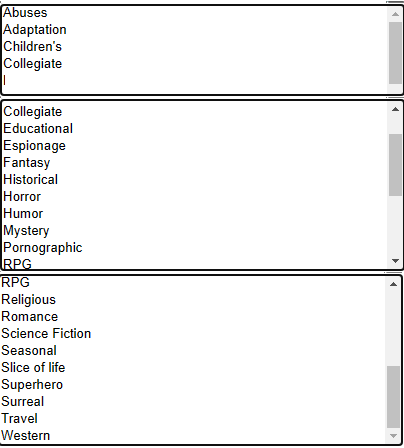

Below you can see the official genres on IFDB (sorry for the mess, modified in Paint):

tl;dr: Mystery still strongly connotes (at least to me) the story of a protagonist functioning as a detective uncovering and connecting clues to solve a crime.

Definitions vary from media to media, and I imagine there might also be differences as you move from region to region. (My experience is exclusively American.)

In publishing, genre has taken on a specific meaning beyond category. Genre novels are highly commercial, usually plot-driven books, that mostly conform to the tropes associated with their primary category. If you managed to find a bookstore that hasn’t gone out of business, inside you’d find several large sections for genres: romance, mystery, science-fiction/fantasy[1], suspense/thrillers, etc.

Of course, there are other novels in the store that aren’t in any of those categories. These non-genre fiction books are called literary fiction. They tend to be more character driven, more cerebral, and more thematic. You’ll find them in a section of the store labeled “fiction.”

For a long time, publishers pushed back against cross-genre books because they were harder to place in bookstores. Should a mystery in a science fiction milieu be displayed in the sci-fi/fantasy section or the mystery section? Genre-fiction is the profit machine for publishers—a genre-bender is inherently at a disadvantage. When they did release a cross-genre book, it was because they felt it could succeed if marketed in one genre.

The Da Vinci Code is structured as a mystery story: It opens with a murder, our protagonist takes on the role of amateur sleuth, uncovering clues, and, in the end, identifying the killer. Dan Brown’s intent was to write a thriller (or so I’ve read), and thus it also embraces many of the tropes that thriller fans enjoy. I believe that, at least initially, it was categorized as a thriller alongside his earlier books. When it became a breakout success, I imagine reprints may have been place throughout stores, in mystery and even literary fiction.

The Handmaid’s Tale is speculative fiction, and thus you might have expected it to find it in your bookstore’s science fiction & fantasy section. To many, it’s probably also a horror. But it’s a very character-centric story with thematic elements, and there’s not one alien or wizard in the whole thing, so it got slotted in literary fiction.

Unsurprisingly, you’ll find Nora Robb’s[2] mysteries in the mystery section. Yet the series is cross-genre since each story is set in a speculative future where technological advances have changed how the world works.[3]

Nowadays, with online shopping, books and other media are easier to market in multiple categories. So, while the genre-fiction system still exists, cross-genre and genre-bending works that defy the established hierarchy of categories have grown more numerous. Instead of genres, we might want to tag stories with any number of appropriate labels. But be aware that labels, like mystery, that match those of traditional genres are going to impart strong connotations for many.

[1] Sometimes called “speculative fiction.”

[2] Nora Robb is a pen name.

[3] Or so I’m told. I haven’t read any of them.

Which is, in every sense except the literal label, a genre.

Perhaps it is more like a label for something that is liked by the cultural elite, but not too liked by the unwashed masses, analogous to art film. Tarkovsky’s Solaris and Stalker are science fiction and art films, just like Gabriel García Márquez is both literary fiction and magic realism.

Perhaps it is more like a label for something that is liked by the cultural elite, but not too liked by the unwashed masses, analogous to art film.

When I worked in the bookstore, the “Literature” section kind of served multiple purposes:

- Fiction which didn’t slot neatly into a mass-market or “pulp” genre we had another shelf for - mystery/SF/romance/horror - or by an author not known to work in a specific genre.

- Classics that are often taught in school - Dracula is ostensibly horror, but is also classic literature.

- Any fiction in a QP format - QP = “quality paperback” which is referring to the quality of the manufacturing and not the words. Any unusually-sized softcover novel with nicer material and paper that isn’t a MM - “mass market” paperback which are all uniformly-sized with cardboard covers and usually grayish paper that has been recycled like newsprint.

Mass Market paperbacks are a book you grab in the airport just to read that fit nicely in a normal-sized bag and not something to feature on a shelf in your library just because the book is pretty. Much of this was logistical since books published in a QP format at whatever physical size the publisher felt was most interesting would not fit neatly onto the special genre shelves set specifically to contain large numbers of mass-market paperbacks with spines-aligned out.

So in some cases, publishing houses could get a book into “literature” just by the format and size they created the book in. High-profile books got a hardcover first. Books the publishers wanted to feature often got a QP (or if they were shorter novels that wouldn’t command a hardcover premium price), and straight-genre fiction often is initially published in MM unless the author was extremely high-profile. Stephen King would usually get a hardcover and then go straight to MM because those were his most lucrative price points for people who read and collect his books.

I think there is some confusion because a large chunk of literary fiction would be categorised as drama if it was a movie, which really is a genre: real world setting, focus on the inner lives of the characters and so on. But modernist stuff like Kafka, Calvino, Borges, or Burroughs, or classics like Dante, Homeros, or Voltaire is nothing like that, but still considered literary fiction.

So in some cases, publishing houses could get a book into “literature” just by the format and size they created the book in.

That’s really interesting. So, literally judging a book by its cover to decide whether to put it in the (more culturally respected) literary section. Next time I go to the bookshop, I’m going to look if they do it too.

I seriously don’t think it was insidious in any way. Publishers knew what they had, and I assume they wouldn’t commit a budget for an unusually-sized book unless they seriously didn’t believe it genre fiction - which was just as important and lucrative a business as the high profile stuff.

It could backfire. If we got a weird-format book that didn’t sell, the easiest place to get rid of it was on the remainder table, whereas lower-profile MM could hang around in the corner of the regular shelves without being so obtrusive.

I was thinking more about the author’s projection of a cultured image: “Look, my book is in the “serious literature”-section.”

But then, the author probably doesn’t have much say about the format in which the book is printed, or the way it’s put into market in general. Unless you’re Stephen King or something.

I liked John Irving’s early work quite a lot (Cider House Rules was one of my favs). I remember reading an interview with him where he characterized himself as a “literary novelist” which amused me as being somewhat pretentious for a man who writes meandering stories about wrestling at New England prep schools and non-conformative sexual relationships.

Reading the explanations of others in this thread who are more familiar with the publishing industry has helped me better understand what “literary fiction” means.

Part of the secret here is that genres are first and foremost a marketing tool! So they’re kind of tautological in that any genre is defined by what the audience expects to see from a work in X genre, and why certain genres have extra things associated with them that aren’t implied from the name (ex: YA literature).

Part of the secret here is that genres are first and foremost a marketing tool! So they’re kind of tautological in that any genre is defined by what the audience expects to see from a work in X genre, and why certain genres have extra things associated with them that aren’t implied from the name (ex: YA literature).

I think this is the core of it. Genre is an assemblage of perceptional priors that calcify traits into reproducible mechanics, such that a community can develop into the continuously negotiated-against-the-baseline identity, which sounds a lot like a marketable opportunity to everyone employed by marketable opportunities in publishing. In that sense, genre can be a useful thing to play with, with “noir” or “low fantasy” being coherent sets of stylistics rich with distinct cultural materials, but it’s not really helpful to take the concepts of genre too literally, because it’s an ultimately illusory signposting intended to filter reader demand into delimitational captures, which is how you get stuck.