Welcome back to…

Chapter 4 (Part 1)

This is a shorter chapter, so let’s go all out!

Section 41 is new kinds.

Every value has a kind. The kind of 10 is “number”; the kind of 11:30 PM is “time”; the kind of “jinxed wizards pluck ivy from my quilt” is “text”; and so on. The Kinds index panel shows the kinds present in the current Inform project, which will always include a wide range of built-in kinds, and usually also some new ones created in that project.

We mentioned kinds in the last chapter. Kinds are great; they’re pretty much the only way to make indistinguishable objects, but they’re also useful if you don’t want to repeat a lot of work. I made a ‘kind of room’ yesterday to for a vast underground lake that was a bunch of identical rooms in a row (I could have just used an ‘instead of going rule’ and a counter but this seemed more fun). I’ve also used kinds for the wax figures in my wax museum, for climbing rocks, spell scrolls, books, spears, and dancing silks.

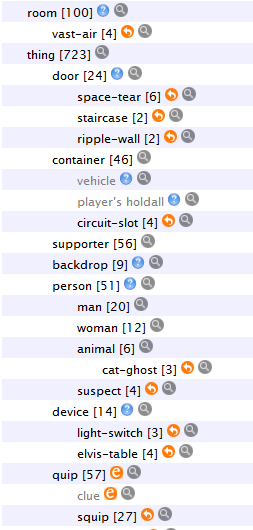

Kinds can be ‘nested’:

For example, if we write:

Growler is an animal in the Savannah.

then Growler is an “animal”, which is a kind of “thing”, which is a kind of “object”. When we talk about “the” kind of Growler, we mean “animal”, the most specific one, but actually he belongs to all of those kinds.

Kinds are declared like so:

A Bengal tiger is a kind of animal.

Given that, we can then write:

Growler is a Bengal tiger in the Savannah.

Apparently you can also insert other kinds in between preexisting kinds, which kind of seems like bad praxis, but I do this with regions a lot so oh well.

That’s easy enough. Adding “mammal” now looks awkward, though, because it seems to belong in between the two. All Bengal tigers are mammals, but not all animals are. But Inform can sort this out:

A mammal is a kind of animal. A Bengal tiger is a kind of mammal.

If we look at the Kinds index, we should indeed see a hierarchy:

object > person > animal > mammal > Bengal tiger

Inform doesn’t have hardcoded scientific reasoning, so the documentation points out that it doesn’t know that a ‘man’ and a ‘woman’ are an animal, and it makes sense from a coding perspective because kinds are about what actions result from interacting with the object and not about what they inherently mean.

(There was a heavy simulationist school in the early 2000s that saw IF as a stepping school to better computer simulation and really wanted the computer to actually understand things, but I’m of the school that fooling the player into thinking the computer knows what it’s doing is just as good as it actually knowing.)

You can make new kinds of things, but can’t make new numbers. Instead, you make a new thing called a ‘value’, which we’ll talk about later.

Example 43 is about adding synonyms for an entire kind, which is precisely the main thing I use kinds for.

A cask is a kind of thing. A cask is always fixed in place. Understand "cask" or "barrel" as a cask. Understand "casks" or "barrels" as the plural of cask.

This is the true power of Inform (and similar high-end languages), the ability to type a few words and broadly affect dozens of objects. I love it.

Section 4.2 is ‘Using new kinds’.

This sections makes a kind of room (this is the exact example I looked up last night for my own game).

It adds a little tip about Inform not being a mind reader:

Inform often doesn’t mind in what order it is told about the world, but it may need to know the name of a kind before that kind can be used. For example,

A coffer is a kind of container. In the Crypt is an open coffer.

makes sense to Inform and results in the creation of a new thing, just called “coffer” in the absence of any other name to give it, whose kind is “coffer” and which is initially open. Whereas if Inform reads:

In the Crypt is an open coffer.

without knowing that “coffer” is a kind, it simply makes a thing called “open coffer” (and which is not a container).

Section 4.3 is Degrees of certainty. We can use the phrases ‘usually’ and ‘always’ or ‘seldom’ or ‘never’ to make broad statements. I don’t like to use ‘always’ or ‘never’, but I believe their primary purpose is to keep the author from accidentally making bad mistakes.

These words let you define global attributes for a whole kind:

A dead end is usually dark.

or

A dead end is always dark.

Both of these make all dead ends dark by default, but the second one throws an error if you happen to make one dead end lit, while the first will not throw an error.

Example 44 has some commentary on trends in IF (probably written over 15 years ago):

In recent years there has been a strong trend towards providing unique descriptions for all implemented objects. Often this is a good idea, but there are also contexts in which we may want to discourage the player from looking too closely at some things and concentrate his attention on just a few interesting ones.

This is pretty much requisite for all IF games now except for those that specifically eschew deep implementation (such as Arthur Di Bianca’s restricted verbset games).

This example shows how to assign a default description to a whole kind (in this case, ‘things’):

The description of a thing is usually "You give [the noun] a glance, but it is plainly beneath your attention."

Example 45 is ‘Something Narsty’, which defines a whole ‘kind’ of staircase:

A staircase is a kind of door. A staircase is always open. A staircase is never openable.

I do stuff like this too. In my current game, portals that are rips or tears in space open up inside a blowing-up space ship:

A space-tear is a kind of door. A space-tear is usually unopenable. A space-tear is usually open. Understand "tear" or "space" or "tear in space" or "rip" as a space-tear.

Section 4.4 is Plural assertions, which is a section I have purposely never read because it always looks intimidating, the first three or four lines don’t make it clear to me what a plural assertion is, and what I don’t know can’t hurt me.

But I have to bite the bullet.

Oh, apparently it’s just doing multiple things at once. That’s not scary!

It’s saying you can type

The high shelf and the skylight window are high-up fixtures in the Lumber Room.

instead of

he high shelf is a high-up fixture. The skylight window is a high-up fixture. The high shelf is in the Lumber Room. The skylight window is in the Lumber Room.

This is logical and I think I’ve used it before, but it would be convenient. Part of this is a subtle lie, Inform dressing up in a human-suit, since you don’t actually need the ‘s’ for this to compile (you can just say 'are high-up fixture in Lumber Room).

I have way too much redundant code, like this snippet in my game:

There is a tango climbing-rock. There is a romeo climbing-rock. There is an oscar climbing-rock. There is a uniform climbing-rock. There is a bravo climbing-rock. There is a lima climbing-rock. There is an echo climbing-rock. There is an alfa climbing-rock. There is a hotel climbing-rock. There is an india climbing-rock. There is a yankee climbing-rock. There is a sierra climbing-rock.

(if the samples of my code do not contribute to the post, please let me know!)

The section ends with this nugget:

Inform constructs plurals by a form of Conway’s pluralisation algorithm, which is quite good - for example, it gets oxen, geese (but mongooses), sheep, wildebeest, bream, vertebrae, quartos, wharves, phenomena, jackanapes and smallpox correct. But English is a very irregular language, and multiple-word nouns sometimes pluralise in unexpected ways. So we sometimes need to intervene:

A brother in law is a kind of man. The plural of brother in law is brothers in law.

One of the things no one can agree on in my church is on the proper plural of Book of Mormon. Is it Books of Mormon? Book of Mormons? The leadership mostly closed ranks to use ‘copies of the Book of Mormon’, so that’s where we’re at now.

Example 46, Get me to the Church on Time (oh maybe I saw that out of the corner of my eye and it reminded me of church) uses kinds of clothing to prevent people from wearing more than one pair of pants.

Instead of wearing a pair of pants when the player is wearing a pair of pants (called the wrong trousers):

say "You'll have to take off [the wrong trousers] first."

This ‘called the’ thing really confused me for a long time. I never know when Inform will accept it and throw it in all sorts of places.

Section 4.5 is ‘Kinds of Value’. This is for things like numbers and texts.

This is something I have rarely used, but is very powerful. Here is an exapmle:

Brightness is a kind of value. The brightnesses are guttering, weak, radiant and blazing.

“Brightness” is now a kind of value on a par with (for instance) “number” or “text”. There are only four possible values, named as above. Kinds of value like this, where there are just a few named possibilities, are extremely useful, as we’ll see.

I just started using values in my current game. Here is an examples:

Nato-code is a kind of value. The nato-codes are Tango, Romeo, Oscar, Uniform, Bravo, Lima, Echo, Alfa, Hotel, India, Yankee, Sierra.

A climbing-rock has a nato-code. Understand the nato-code property as describing a climbing-rock. A climbing-rock is usually alfa.

There are also quantitative values, which I don’t really understand using since it’s just a number:

Weight is a kind of value. 1kg specifies a weight.

I usually just use ‘weight is a number that varies’ for stuff like this. Here’s Graham’s explanation:

The difference here is not the way we create the kind, but the way we tell Inform what the possible values are. Instead of a list, we teach Inform some notation. As a result, “26kg” is now a value, for instance. Quantitative kinds like this are sometimes called “units”, because - as in this example - they’re often units in the sense of measuring things. Many Inform projects never need units, but they can still be very useful, and they’re described in detail in the chapter on “Numbers and Equations”.

4.6 is Properties Again. Although the first thing it does is talk about relations:

Relations are really the central organising idea of Inform, and we’ve seen them many times already:

Growler is in the Savannah.

expresses a relation called “containment” between Growler and the Savannah. Much more about this in the chapter on Relations: for now, let’s go back to the simpler idea of properties.

The only new thing in this section is that the Kinds index in Inform lists useful things. I didn’t even know this existed! Let’s look at my kinds tab:

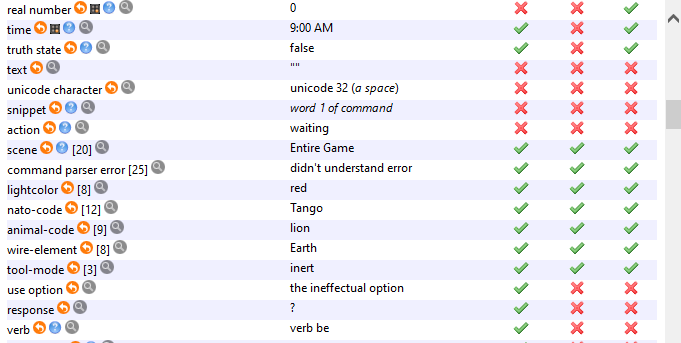

This is very useful! I only captured part of the index. Here is another segment with every column included:

The columns with checks are labelled ‘repeat’ for things you can repeat through, ‘props’ for things that can have properties, and ‘under’ for things that can be used in an ‘understand’ message.

The reason some things can’t have properties is that there are infinitely many of them (like numbers).

Section 4.7 is new either/or properties. Boy, I love these and use them all the time.

[E]very property must be created in a way which lays out what values are allowed to have it. The Standard Rules built into Inform say that

A thing can be fixed in place or portable.

We can make our own such properties.

To go back to our example “dead end” kind:

A dead end is either secret or ordinary.

This creates just one new property, not two. The names are taken as the two states of a single either/or property: secret means not ordinary, ordinary means not secret. Alternatively, we could just say:

A dead end can be secret.

in which case the opposite of “secret” would be “not secret”.

Now I could have sworn that you can’t make these properties for specific kinds; I swear when I do that I get an error and have to go back and make it a property of all things, which is annoying but I do it.

But looking back, it seems that was caused by me having typos in my kinds, so I’ve kind of been doing things wrong for a long time…

This is really messing with my head. My worldview is changed.

Single things can have either/or properties, which I have gotten to work before. Here is the example:

The umbrella is carried by the player. The umbrella can be open.

Example 47 is Change of Basis, which adds sleeping and waking states:

A person is either awake or asleep. A person is usually awake.

Is there a properties index in Inform? It’d be fun to see all of them laid out. But I don’t see one.

Section 4.8 is New Value Properties. This is where instead of ‘either/or’ properties, you attach things like texts or numbers.

This is just objects from OOP, where you can have an ‘object’ with associated functions and numbers and strings, but here the ‘object’ is a physical object. So like, Very Object Oriented Programming.

A dead end has some text called the river sound. The river sound of a dead end is usually "a faint whispering of running water". The Tortuous Alcove has river sound "a gurgle of running water".

This has inflexible ‘typing’ (is that the word?), so if you try to say something like:

The river sound of the Tortuous Alcove is 7.

…then Inform would object, because the number 7 is the wrong kind of value to go into the “river sound” property. If we need a numerical property, we can try this instead:

A dead end has a number called the difficulty rating. The Tortuous Alcove has difficulty rating 7.

You can establish defaults for value properties:

The river sound of a dead end is usually "a faint whispering of running water".

If you don’t provide a default, Inform will, usually a blank.

Example 48 is about giving flavor to things:

A food is a kind of thing that is edible. Food has some text called flavor. The flavor of food is usually “Tolerable.”

In my extension, Quips and Conversation, I give properties to conversation topics (called ‘quips’ in honor of Emily Shorts similar terminology):

A quip has an object called the target. The target of a quip is usually nothing.

A quip can be TargetGiven or MeihTarget. A quip is usually MeihTarget.

A quip has some text called TargetResponse. The TargetResponse of a quip is usually "You get no response."

A quip has some text called TargetSummary. The TargetSummary of a quip is usually "You already tried talking about this."

Example 49 is Straw Boater, which gives ‘movement sounds’ to vehicles. It cleverly uses the fact that not setting a default for a text value will just print nothing, which honestly feels more like a bug exploit than a technique, since you could just explicitly set the default of your property to be nothing.

Section 4.9: using new kinds of values in properties. This combines value properties and assigning values to kinds. As an example:

Brightness is a kind of value. The brightnesses are guttering, weak, radiant and blazing.

The lantern has a brightness called the flame strength. The flame strength of the lantern is blazing.

What’s particularly nice is that we can now use the names of the possible brightnesses - “weak”, “blazing” and so on - as adjectives. Inform knows that “The lantern is blazing” must be talking about the brightness property, because “blazing” is a brightness.

A dead end is a kind of room with printed name "Dead End" and description "This is a dead end, where crags in the uneven rock are caught by the [brightness of the lantern] flame you hold aloft. Despite [river sound] there is no sign of the stream." A dead end is usually dark.

You can also assign properties to values:

A brightness can be adequate or inadequate. A brightness is usually adequate. Guttering is inadequate.

This is actually where my climbing rock example comes from. I wanted to make a bunch of identical rocks, each with a different letter of the nato alphabet on it. So I made nato-code into a kind and gave one to every rock, and added this line:

Understand the nato-code property as describing a climbing-rock. A climbing-rock is usually alfa.

So now if I say ‘there is a tango climbing-rock in ____’, then I can type in ‘X tango rock’ and get a response. It’s the perfect way to make a bunch of identical objects with slightly-different properties and honestly shows Inform’s power.

Finally, in this section, you can assign numerical values to your earlier text values:

Temperature is a kind of value. 100C specifies a temperature.

A brightness has a temperature. The temperature of a brightness is usually 700C. The temperature of blazing is 1400C. The temperature of radiant is 1100C.

The description of the lantern is "The lantern shines with a flame at [temperature of the brightness of the lantern]."

There are 4 examples in this section. To begin with we have Undertomb 1 and Undertomb 2, examples 50 and 51. The first adds ‘river sound’ to each room, while the second adds a brightness level to a lantern that decreases over time with some new code we haven’t seen before:

After waiting in the Tortuous Alcove when the brightness of the lantern is not guttering:

now the lantern is the brightness before the brightness of the lantern;

say "You wait so long that your lantern dims a bit."

So ‘the brightness before the brightness of the lantern’ is the new thing here.

I’ll admit, I generally just use numerical variables for this kind of thing. I have a lot of stuff like ‘pillar-level is 0’, ‘pillar-level is 1’. It’s functionally equivalent and often easier for me to read.

Example 52 is The Crane’s Leg 1. This is a very convoluted example where materials and numbers are assigned to everything, but each kind has an associated ‘ideal’ object which we can then imitate. It uses relations and is a lot to discuss right now so I won’t. If you like this kind of thing the Emily Short games Metamorphoses and Savoir Faire are really fun and pull these kinds of tricks all the time.

Example 53 is Signs and Portents, which adds ‘Destination’ as a value:

Destination is a kind of value. The destinations are London, Abingdon, Luton, Weston-super-Mare, Runnymede, Hell, and Low Noon.

and adds them to a signpost.

Section 4.10 is Conditions of things.

This is basically a way to define values by using wording similar to either/or properties:

The cask is either customs sealed, liable to tax or stolen goods.

Initially the cask will be “customs sealed”, the first value we gave. We could now write, for instance,

The description of the cask is "A well-caulked Spanish wine cask.

[if liable to tax] It really is a shame to have to pay duty on it!"

You can also do this for kinds:

Colour is a kind of value. The colours are red, green and white.

A colour can be bright, neutral or flat. Green is neutral.

Now in fact these properties are not anonymous: Inform has worked out names for them, even though we didn’t give any. The usual arrangement is that the name is the name of the object with the word “condition” tacked on: for instance, “cask condition”. So we could write:

The printed name of the cask is "wine cask ([cask condition])".

This kind of statement is the thing I ran fleeing from terror of in the past, but I have to post here, so let me puzzle it out. It seems like if you list more than two things in a ‘thing1 can be ____ or…’ statement, then instead of being an either/or property it reinterprets it to be:

thing1 has a [whatever our value is called] called thing1 condition.

If you do this again, the next one is called ‘thing1 condition 2’.

But, you can name it what you want as follows:

A fruit can be unripened, ripe, overripe, or mushy (this is its squishiness property).

And now the resulting property and kind of value would be called “squishiness”.

This is the kind of thing that makes my head hurt. I’d much rather just stick to text properties and numerical properties for most of this kind of thing. Like just saying:

A fruit has some text called the ripeness. The ripeness of a fruit is usually "unripened".

And then do a bunch of if statements, which you’d have to do with values anyway.

Section 4.11 is default values of kinds, which are always useful. The default of texts is “”, the default of numbers is 0, and so on. Defaults are listed in the kinds index I screenshotted above.

You can only assign defaults to things that exist in the world, so you can’t say ‘default value of vehicle’ if the game has no vehicles.

4.12 is values that vary. This is just creating variables instead of hardcoded properties. Most of my values vary. You can code this in three ways:

The right way (my name for it):

The prevailing wind is a direction that varies. The prevailing wind is southwest.

The wrong way (my name for it):

The prevailing wind is a direction variable. The prevailing wind is southwest.

or the “smooth, but going to cause you problems later debugging your code” way:

The prevailing wind is initially southwest.

Apparently you are not required to specify what value a variable starts with, which is something I always thought would make my computer explode. If you don’t specify, it just starts at the default (which is 0 for numbers).

We can have variables of any of the kinds of value, including new ones, but should watch out for a potential error. If we write:

The receptacle is a container that varies.

in a world which has no containers at all, Inform will object, because it will be unable to put any initial value into the receptacle variable.

As a final note on kinds, when Inform reads something like this:

Peter is a man. The accursed one is initially Peter.

it has to make a decision about the kind of “accursed one”. Peter is a “man”, so that seems like the right answer, but Inform wants to play safe in case the variable later needs to change to a woman called Jane, say, or even a black hat. So Inform in fact creates “accursed one” as an object that varies, not a man that varies, to give us the maximum freedom to use it. If we don’t want that then we can override it:

Peter is a man. The accursed one is initially Peter.

The accursed one is a man that varies.

In this way, Inform is a lot like GPT. Both are marvelous and easy for people bad in certain areas like writing and drawing because it can guess what you want and fill it in. They also are very frustrating and hard to master for very technical and experienced users because it can guess what you want and fill it in.

Example 54 is Real Adventurers Need No Help, which lets you turn off hints.

A permission is a kind of value. The permissions are allowed and denied.

Hint usage is a permission that varies. Hint usage is allowed.

Check asking for help for the first time:

say "Sometimes the temptation to rely on hints becomes overwhelming, and you may prefer to turn off hints now. If you do so, your further requests for guidance will be unavailing. Turn off hints? >";

if player consents:

now hint usage is denied;

say "[line break]Truly, a real adventurer does not need hints." instead.

Section 4.12 is Values that never vary (is this just global variables/constants? This is my first time hearing any of this).

Rather than typing “55” (say) every time it comes up, we might prefer to write:

The speed limit is always 55.

at the start of the source text, and then talk about “the speed limit” every time we would otherwise have typed “55”.

Yeah, isn’t this just magic numbers/global constants? I’m going to google ‘programming magic numbers’ and see what comes up.

Oh, looking it up says this is the opposite of magic numbers, and that this is a very good thing. Magic numbers are where random numbers appear in your code for no reason, while the preferred practice is giving them names. Which is what this section teaches.

We just use the word always:

The speed limit is always 55.

and use that throughout the code:

if the speed is greater than the speed limit, ...

and this allows us to make changes everywhere by changing that initial line:

The speed limit is always 70.

Hmm, this fixes a little problem I was having, and I just went through and replaced a common thing I use in my code with a global constant.

This section ends with a statement that I can’t really parse. It says:

“Speed limit” is then a number constant. Any attempt to set this elsewhere, or change its value, will result in a Problem message,

(so far this makes sense)

and moreover it can be used in contexts where only constant values are allowed. For example,

The generic male appearance is always "He is a dude."

Trevor is a man. The description of Trevor is the generic male appearance.

means that the SHOWME TREVOR testing command produces, among other data:

description: "He is a dude."

Can anyone explain this to me? Which part of this only works for constant values, and would fail if replaced with a variable value?

Anyway, Section 4.14 is Duplicates. This is useful when you want multiple indistinguishable copies of something, but that is almost always annoying. (There are some typical ‘help’ questions that people ask on here that almost always make me think ‘that game will not be fun and/or the author probably won’t finish it’. Those include inventory limits, implementing toilets, making realistic elevators, and making indistinguishable objects. Then there are ‘I will almost certainly not play that game unless forced to’, which are when people ask about real-time events in Inform, timed text in Twine, or preventing UNDO use. I’ve found great games that break all of those above rules so they’re not real).

All you need is to define a kind and then declare multiple of it.

So:

A square is a kind of thing. In the Lab are two squares.

(This is a simplified example of the manual example, which used nested kinds).

You can’t make more than 100 duplicates of something due to memory issues.

Using too many duplicates can also clog up other inform functions:

If there are very many items in the same place, commands like TAKE ALL and DROP ALL may mysteriously not quite deal with all of them - this is because the parser, the run-time program which deciphers typed commands, has only limited memory to hold the possibilities. It can be raised with a use option like so:

Use maximum things understood at once of at least 200.

(The default is, as above, 100. Note the “at least”.)

There is a caution about a bizarre event that can occur:

Thirdly, note that Inform’s idea of “identical” is based on what the player could type in a command to distinguish things. In a few cases this can make items unexpectedly identical. For example:

The Lab is a room. A chemical is a kind of thing. Some polyethylene and polyethylene-terephthalate are chemicals in the Lab.

results surprisingly in “You can see two chemicals here”, because the run-time system truncates the words that are typed - POLYETHYLENE and POLYETHYLENE-TEREPHTHALATE look like the same word in a typed command. So Inform decides that these are indistinguishable chemicals. Typically words are truncated after 9 letters, though (unless the Glulx setting is used) punctuation inside a word, such as an apostrophe, can make this happen earlier.

Example 55, Early Childhood, has multiple blocks that can be repainted. It starts with kinds ‘red block’ and ‘blue block’, but kinds can’t be changed in gameplay, so it switches to using properties:

The colours are red, blue and green. A block is a kind of thing. A block has a colour. A block is usually blue

Then it goes to adding a way to print the color of a block:

Before printing the name of a block: say "[colour] ". Before printing the plural name of a block: say "[colour] ".

(This is code I’ve directly copied in my project from this example before).

Finally it adds a way for the user to type the color and have it recognized:

Understand the colour property as describing a block.

This is a vital thing that I think ought to have been in the main text. Quite a lot of good stuff is hidden in the examples.

(To be continued: I exceeded the page limit)