Chapter 3 Continued (3.8-3.26)

Chapter 3.8 is Scenery! ‘Scenery’ has to be one of the most common words in my code outside of standard English words like the/of/a/etc.

Any thing can be scenery, and this does not bar it from playing a part in the story: it simply means that it will be immobile and that it will not be described independently of its room. Being immobile, scenery should not be used for portable objects that are meant to be left out of the room description.

Pretty much everything in a room that isn’t takable ought to be scenery.

This can cause some problems if you have some very dense room descriptions. This is especially bad when people are modeling their actual kitchen and include every appliance, every cupboard, etc.

Ryan Veeder has a great way of writing strong room descriptions with few objects in it, and even has a great blog post about it.

Scenery has two properties: it doesn’t move and it isn’t described. You can make something immovable but still described by calling it ‘not portable’ or, I think, ‘fixed in place’, but I’ve often wished for the opposite: a word for something takeable, but not described, at least temporarily.

An interesting side bit of trivia:

If a supporter is scenery, it may still be mentioned in the room description after all, but only as part of a paragraph about other items, such as

On the teak table are a candlestick and a copy of the Financial Times.

The first example in this sections is Disenchantment Bay 2.0. It gives an example of just adding everything in the room description as scenery:

“Some navigational instruments, some scratched windows, a sign, a radar display, and some radios are scenery in the cabin.”

I personally have my own little template, which is

____ is scenery/a thing/etc. in _______. The printed name of ______ is _____. Understand ____ or _____ or ____ as _____. The description of _____ is _____.

Someone upthread posted a similar template but it includes “instead of doing anything with _____ instead of examining it”. That would probably improve my games, to be honest, but I’m not sure that a single catchall can work for things as disparate as ‘listen to’ or ‘push’ or ‘search’, especially if writing different catchalls for all things. But I guess that’s what testers are for, is seeing what responses don’t make sense. (Thanks testers!)

Example 16 is Replanting, which has an interesting rule:

The Orchard is a room. "Within this quadrille of pear trees, a single gnarled old oak remains as a memory of centuries past." The gnarled old oak tree is scenery in the Orchard.

Instead of taking some scenery: say "You lack the hulk-like strength."

This is an example of a custom ‘can’t take that message’ for the tree, which really is vital for most scenery; I have a lot of these in my code. But what’s interesting is the way it’s phrased:

Instead of taking some scenery: say "You lack the hulk-like strength."

I didn’t know you could write it like that, but I guess it should make sense. I suspect inform ignores ‘some’ or ‘a’ when processing this type of command, and just treats scenery as the kind it is, so this is basically like saying ‘instead of taking scenery’.

Section 3.9 is backdrops! Backdrops are scenery that appears in multiple rooms, such as the sky in an outdoor game or the floor in a spacestation.

A backdrop can be placed in a region or a room. This is one reason regions are nice, you can just apply a global change to everything.

You can also do this apparently:

The special place “everywhere” can be given as the location of a backdrop to make it omnipresent:

The sky is a backdrop. The sky is everywhere.

Behind the scenes, backdrops are just a single object that gets physically moved from room to room (I think infocom games did that and it got copied here?)

Disenchantment Bay is again an example here, with a glacier added as a backdrop (although since this is currently a one-room game, it doesn’t do much).

I have a way of classifying actions in my game as ‘physicality’, like ‘touching is physicality’. And then if something is far-off, I say:

Instead of phsyicality when the noun is a distant thing:

say "That's too far away!"

with similar rules for immaterial things.

3.10 is properties holding text.

So instead of being either/or properties like open or closed, you can have properties of a room with text in them.

This is, in a way, Object-oriented programming (with literal objects!) as you can take an object and associate whatever you want with it.

For now, we only mention descriptions, but I usually have a lot of text. For instance, copying Emily Short, in my game conversational topics are called ‘Quips’, and I have a ‘preview’ for each quip as well as a ‘response’ for each quip.

Anyway, for room descriptions, you can write them in three ways. The first two are sensible:

The Painted Room is north of the Undertomb. The description is "...

or

The Painted Room is north of the Undertomb. The description of the Painted Room is "...

But the weird way (and the one that was used in games I learned from) is:

The Painted Room is north of the Undertomb. "This...

So you just put some quotes and start typing. Pretty neat.

3.11 is two descriptions of things. This one really threw me for a loop when I first started coding.

All the example games use the same trick as in 3.10 for objects, so like

There is a leaf in Mudland. "A leaf has fallen, out of season, lying in the mud."

But this isn’t the description of the object, which is a separate thing you set by saying The Description of the object is ".... Instead, this determines what people see when they run into the object, instead of ‘You see a leaf here.’

So this works great, but when I later wanted to modify it, I had no idea how to!

It urns out, this thing is actually a property called ‘the initial appearance’.

It’s used when something has not been ‘handled’, which is Inform’s word for ever taken. I didn’t know Inform’s word for it, so my current game coded something called ‘onceTaken’ which is functionally identical.

Disenchantment bay now adds tons of descriptions of everything in this example.

A new example, Laura, teaches multiple things not mentioned in the section above.

First is that Inform might parser ‘and’ or ‘with’ in names as code, which can mess things up, so you can fix that as follows:

Often it is enough to preface these ambiguously-titled things with “a thing called…” or “a supporter called…” or the like, as here:

South of Spring Rolls is a room called Hot and Sour Soup.prevents Inform from trying to read “Hot and Sour Soup” as two separate rooms, while

The player carries an orange ticket. The player carries a thing called an orange.creates two objects instead of the one orange ticket that would result if the second sentence were merely “The player carries an orange.”

It then mentions we can instead just set the printed name property. I do that for everything in my game; with 10 sub-games, there’s so much overlap that I have to name them weird things with hyphens in it and then change the printed name. For instance, I have a wax statue of the pharaoh Khufu in one sub-game and a mummy pharaoh in another.

Here’s the example:

The City of Angels is a room. The incriminating photograph is carried by the player. The printed name of the incriminating photograph is "incriminating photograph of a woman with blonde hair".

Understand "woman" or "with" or "blonde" or "hair" or "of" or "a" as the incriminating photograph.

Now I actually don’t like the ‘of’ thing here. As the book says,

in the case there were two items with “of” names, the game would disambiguate with a question such as “Which do you mean, the incriminating photograph of a woman with blonde hair or the essence of wormwood?”

What I like to do is to combine ‘of’ with one of the words. So if there is a ‘box of gold’, I’ll say:

Understand "box" or "box of " or "gold" as the box of gold.

That way, it’ll only recognize ‘of’ as the box if people are specifically typing ‘box of gold’.

There is a pitfall to the ‘understand’ method:

[I]f we specify a whole phrase as the name of something, all the words in that phrase are required, in the order given. Thus “Understand “blonde hair” as the photograph” would require that both “blonde” and “hair” be present, and would not recognize >X BLONDE, >X HAIR BLONDE, or >X HAIR.

New authors make this mistake all the time, and unfortunately so do I. If you’re playing an Inform game and see a ‘blue chest’ and type X CHEST and don’t get a response, they probably made this mistake.

For some real advanced understanding, the author provides this:

We can create tokens, such as "Understand “blonde hair” or “hair” as “[hair]”, and then use these tokens in match phrases. This saves a good deal of time when we want to specify a number of different but fussy alternatives. So, for instance, here is a drawing that would not respond to >X OF, or >X BROWN EYES, but would respond to >X DRAWING OF MAN WITH BROWN EYES, >X MAN WITH BROWN EYES, and so on:

The drawing is carried by the player. The printed name of the drawing is "drawing of a man with brown eyes". Understand "eyes" or "brown eyes" as "[brown eyes]". Understand "man" or "man with [brown eyes]" or "brown-eyed man" as "[man]". Understand "[man]" or "drawing of [man]" or "drawing of a [man]" as the drawing.

Section 3.12 is Doors! Useful but complicated.

Doors go between rooms:

The heavy iron grating is east of the Orchard and west of the Undertomb. The grating is a door.

The standard for doors is:

In the absence of any other instruction, a newly created door will be fixed in place, closed and openable.

If you use doors like this, you don’t include any connection directly between rooms, just the door itself.

Amusingly, this section borrows the name of its example rooms from Ursula Le Guin’s book ‘The Tombs of Atuan’, an excellent book I read for the first time last year:

The red rock stair is east of the Orchard and above the Undertomb. The stair is an open door. The stair is not openable.

In this example, we’ve made a stairway into a door. This is convenient; anything that people might enter or interact with assuming it will lead them to another room makes a good door.

Apparently there are also one-sided doors (which is great for me because I want one coming out of my Graveyard in my game):

The blue door is a door. It is south of Notting Hill. Through it is the Flat Landing.

(I’m literally copying this into my game as I write this).

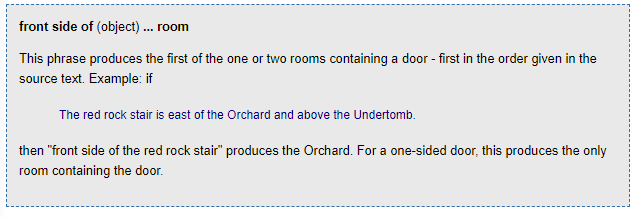

Doors have front sides and back sides (apparently!) and this is put in the special ‘important boxed format’ of the manual, which I think is the first appearance of this format (here is a picture of the special box, for those using screen readers):

So the front side of a door is the first room in the code, and the back side of a door is the second room in the code (I presume we mean here the first room in specifically the declaration of the door, not the room of the two which is first mentioned in the source text at all).

A classier way to handle it is ‘other side of the door from _____’. In the examples given, this works if the blank is a room, but it also mentions the word ‘object’, so maybe you can type anything there?

with some experimentation in a sandbox game, it seems it only works for rooms, not objects.

Similarly, we can extract the direction of (door) from (room)

We have disenchantment bay again, this time simply adding a new door and a new room: the deck. This automatically places the glacier backdrop in the deck.

Example 21 is Escape, which introduces a window which serves both as a door and as a way to see the other side:

Instead of searching the window:

say "Through the window, you make out [the other side of the window]."

Example 22, Garibaldi 1, gives you a machine that prints out the status of every door in the game and which rooms it connects:

The security readout is a device. The description of the readout is "The screen is blank."

Instead of examining the switched on security readout:

say "The screen reads: [fixed letter spacing]";

say line break;

repeat with item running through doors:

say line break;

say " [item] ([front side of the item]/[back side of the item]): [if the item is locked]LOCKED[otherwise]UNLOCKED[end if]";

say variable letter spacing;

say paragraph break.

This could be really useful for debugging a door-heavy game!

Next is locks and keys. I highly recommend using Locksmith for any game with a bunch of locks and keys in it.

Here are three ways to match keys to doors:

It seems unwise for a door in Notting Hill to be unlocked, so:

The blue door is lockable and locked. The matching key of the blue door is the brass Yale key.Since the second sentence here is a little clumsy, we can equivalently say

The brass Yale key unlocks the blue door.Yet a third way to say this is:

The blue door has matching key the brass Yale key.

Containers can have keys, but not supporters.

Keys don’t have to be actual keys; you can have lockpicks or something more exotic (like a raw steak for a flesh-eating door, or that weird animal head door in Zork II).

3.14 is devices, something I’ve used several times in my current game. The only thing a device does is it can be ‘switched on’ or ‘switched off’, standard actions in the inform library. Although it’s a bit annoying that you can’t have something be both a device and a container (I think, I’ve definitely gotten errors like that).

This section also mentions that you can make decisions on how to print things based on the status of an object:

The coffin is an openable container in the Undertomb. "[if open]The lid of a plank coffin yawns open.[otherwise]A plank coffin lies upon the dirt floor of the Tomb."

This is good stuff; I spent years trying to figure this out.

Example 25 has Disenchantment bay adding switchable instruments.

Example 26 makes a light switch and previews the introduction of light and dark rooms.

It mentions something very obscure which I’ve tried hard to understand but always fail. This is our first experience with the dreaded ‘scope’:

Finally, we need to deal with a special case. In general, the player cannot interact with other things in a dark room because he can’t see them, but if we adhered strictly to this it would be impossible for him to find the light switch to turn it back on. So we need something from the chapter on Activities to change this:

Terrifying Basement is a room. The light switch is a switched on device in the Terrifying Basement. It is fixed in place.

Carry out switching off the light switch: now the Terrifying Basement is dark.

Carry out switching on the light switch: now the Terrifying Basement is lighted.

After deciding the scope of the player when the location is the Terrifying Basement:

place the light switch in scope.

Upstairs is above the Terrifying Basement.

Section 3.15 is light and darkness itself!

Rooms are either ‘dark’ or ‘lighted’.

When the player is in a dark room, he can still go in various directions, but he cannot see the room description or interact with any of the objects in the room, except those he is holding.

This means the description of a dark room will never be printed unless the room is lighted. The standard way to light a room is with a ‘lit’ object, which can shine through transparent containers but not opaque.

3.16 is vehicles and pushable things. I didn’t know vehicles were standard in Inform! I thought the manual had examples on how to make them, but not that they were hardcoded.

Next in the tour of standard kinds is the “vehicle”. This behaves like (indeed, is) an enterable container, except that it will not be portable unless this is specified.

In the Garage is a vehicle called the red sports car.The player can enter the sports car and then move around riding inside it, by typing directions exactly as if on foot: and the story will print names of rooms with “(in the red sports car)” appended, lest this be forgotten.

There is also an extension for rideable vehicles called ‘Rideable Vehicles’ by Graham Nelson.

Example 27 is a simple example of a rideable bike (rideable meaning you go on top of it instead of inside it).

Example 28 is more disenchantment bay. This doesn’t have a vehicle, but does have a pushable container. This contains the seemingly-contradictory but technically correct code:

It is fixed in place and pushable between rooms.

Example 29, Hover, has a floating car kind of thing. This example heavily modifies the rules to let you see the exterior but modified by a blue tint.

This example would have been very useful for my revolving glass door that divides a room into four sections. But c’est la vie:

The container interior rule is listed before the room description body text rule in the carry out looking rules.

This is the container interior rule:

if the actor is the player and the player is in an enterable thing (called current cage), carry out the describing the interior activity with the current cage.

Describing the interior of something is an activity.

Rule for describing the interior of the hover-bubble:

say "The hover-bubble is transparent, but tints everything outside very faintly lavender."

Rule for describing the interior of the hover-bubble when the hover-bubble contains more than one thing:

say "The hover-bubble is transparent, but tints everything outside very faintly lavender. Beside you you can see [a list of other things in the hover-bubble]."

Definition: a thing is other if it is not the player.

Rule for listing nondescript items of the hover-bubble when the player is in the hover-bubble: do nothing.

I honestly handle technical stuff like this with global variables and then hunting down individual rules and saying ‘the ___ rule does nothing when _____’. I do use the rule for listing nodescript items thing. For instance, I have a climbing wall that players can move from rock to rock on, and it was reprinting the whole room text each move, so I added this:

The room description heading rule does nothing when looking is stupid.

The room description body text rule does nothing when looking is stupid.

The offer items to writing a paragraph about rule does nothing when looking is stupid.

To decide whether looking is stupid:

if the climbing-wall is nowhere, decide no;

if the player is not enclosed by pride-room, decide no;

if the current action is not looking, decide no;

decide yes;

I think it catches a little more than I want, but no one has complained yet!

3.17 is men, women, and animals.

A person is a kind of thing, and man, woman, and animal are kinds of people.

Inform has a hard gender binary. Even ‘neuter’ is secretly male:

Because of the existence of "neuter", we sometimes need to be cautious about the use of the adjective "male": since Inform, partly for historical reasons, uses an either/or property for masculinity, neuter animals are also "male".

You can make neuter animals by the way with The spider is a neuter animal in the Bathroom.

Example 30 is Disenchantment Bay again with a Captain.

We’re close to the end, so let’s keep going!

Section 3.18 is articles and proper names!

Inform guesses which kind of indefinite articles you want for things by your use of them in the code:

Suppose we have said that:

In the Ballroom is a man called Mr Darcy.When the Ballroom is visited, the man is listed in the description of the room as “Mr Darcy”, not as “a Mr Darcy”. This happened not because Inform recognised that Darcy is a proper name, or even because men tend to have proper names, but because Inform noticed that we did not use “a”, “an”, “the” or “some” in the sentence which created him. The following shows most of the options:

The Belfry is a room. A bat is in the Belfry. The bell is in the Belfry. Some woodworm are in the Belfry. A man called William Snelson is in the Belfry. A woman called the sexton's wife is in the Belfry. A man called a bellringer is in the Belfry.

In the Belfry is a man called the vicar. The indefinite article of the vicar is "your local".

I had to use this recently because I had a clone of the player called ‘your clone’ that follows you around and copies you.

The subtlest rule here is in the handling of “the”. We wrote “The bell is in the Belfry”, but this did not result in the bell always being called “the” bell: in fact, writing “A bell is in the Belfry” would have had the same effect. On the other hand, “A woman called the sexton’s wife is in the Belfry.” led to the wife always being known as “the” sexton’s wife, not “a” sexton’s wife, because Inform thinks the choice of article after “called” shows more of our intention than it would elsewhere.

I’ve noticed frequently in this chapter that using the ‘called’ way of naming something resolves almost all the problems you might have with compiling. Good to know for the future!

It also includes some collective noun things:

Now we can write:

The water is here. The indefinite article is "some".and this time Inform does not treat the “some water” thing as a plural, so we might read:

You can see some water here. The water is hardly portable.

Example 31 is just the example in the text itself, with the vicar.

Example 32 gives a way to switch between using articles and not:

The Ark is a room. A bearded man is in the Ark.

Instead of examining the bearded man for the first time:

now the printed name of the bearded man is "Japheth";

now the bearded man is proper-named;

say "You peer at him a bit more closely and realize that it's Japheth."

Section 3.19 is carrying capacity. This can be used well, but the people I see most often concerned about it are people just starting out who believe that being meticulously accurate to reality will make people like their games more. This kind of author also tends to put multistep actions for things like driving (making opening the door, getting in, buckling belt, putting key in, etc. separate actions) and will implement every single object in a kitchen or bathroom.

But when used right, this can be good for optimization games or games where the puzzle depends on inventory. Although it can be really annoying; I made a game where you turn into a dog and your inventory limit gets set to 1, and people hated dropping everything. It’s one of my lowest-rated ‘big’ games.

You can make carrying capacities for both supporters and containers, as well as players.

The bijou mantelpiece has carrying capacity 3.

The carrying capacity of the player is 4.

Section 3.20 is Possession and clothing. It introduces a new relation, ‘worn’, which is different than carrying.

Mr Darcy wears a top hat. Mr Darcy carries a silver sword.In fact, Inform deduces from this not only who owns the hat and the sword, but also that Darcy has the kind “person”, because only people can wear or carry.

This is true! In a recent thread, I discovered that making a person wear a watch made them alive and a man.

You can also just declare something wearable:

The gown is wearable.

Example 33 revisits Disenchantment Bay, adding some clothing.

Section 3.21 is The player’s holdall. This is just a way to have a single container the player throws everything in. If you are going to have an inventory limit for the player themself, then having a holdall is a good way to keep everyone from being mad at you.

The Attic is a room. The old blue rucksack is a player's holdall. The player is wearing the rucksack.

The carrying capacity of the player is 3.

Example 34 is Disenchantment bay with a holdall backpack.

3.23 is food. Declaring something ‘edible’ lets you eat it and it disappears, with no other effects.

3.23 is parts of things. This is useful when something needs to serve multiple purposes or have different responses when you try to touch or take different parts of it. For instance, I have a wax figure of Napoleon in my game, and he holds a steel saber. Touching them should feel different!

So you can say stuff like:

The lever, the white button and the brown button are parts of the Chocolate Machine.

Example 35 is Fallout Enclosure. It gives you a way to interact with everything ‘held by’ an object in some way:

An enclosure is a kind of thing. A container is a kind of enclosure. A supporter is a kind of enclosure.

Understand "zap [something]" as zapping. Zapping is an action applying to one thing. The Zapping action has a list of things called the remnants.

Carry out zapping an enclosure:

if the noun holds something:

now the remnants is the list of things held by the noun;

repeat with N running through the remnants:

move N to the holder of the noun.

Example 36, Brown, has a sticky label that can become part of something and then taken again.

Example 37 is a 4-star example (perhaps our first?) that is the complete Disenchantment Bay. It is quite complex and worth checking out!

Section 3.24 is Concealmen, which decides which objets carried by other people are visible or not:

Rule for deciding the concealed possessions of the Cloaked Villain: if the particular possession is the sable cloak, no; otherwise yes.

You can use this trick to hide parts of an object!

The coin is in the Roman Villa. The face and inscription are parts of the coin. Rule for deciding the concealed possessions of the coin: if the coin is carried, no; otherwise yes.

This sounds super useful! Glad I found this…

There is also an either/or property called "described"/"undescribed", intended to be used only as a last resort, but which has the ability to hide something from room descriptions. This not really hiding: the idea is that "undescribed" should be used only for cases where some other text already reveals the item, or where its presence is implicit.

This is the thing I was looking for! Wow, it was ‘undescribed’ all along…this could have saved me so much pain with a key I had opposite of a revolving door…I can’t believe it…

Example 38 is a complex example where someone has concealed possessions, but they become visible if you take his jacket or if you search him.

Section 3.25 is The Location of Something.

Things without specified locations are Nowhere. The player can’t be Nowhere, that gives you a runtime error I’ve gotten too many times.

You can find the location of something, though.

This phrase produces the room which, perhaps indirectly, contains the object given. Example: if the player stands in Biblioll College and wears a waistcoat, inside which is a fob watch, then

location of the fob watchis Biblioll College. In general, a thing cannot be in two rooms at once, but there are two exceptions: two-sided doors, present on both sides, and backdrops. The “location of” a door is its front side, but a backdrop has no location. (Objects which are not things at all, such as rooms and directions, also have no location.)

I use this a lot, it’s good stuff.

There is a technical note which is good here:

The idea of indirect containment is useful enough to have a name: Inform calls it “enclosure”. A thing encloses whatever is a part of itself, or inside itself, or on top of itself, and it also encloses anything that they enclose. And when something moves around, anything it encloses will move with it. In the example above, Biblioll College (a room) and the player (a person) both enclose the fob watch and the waistcoat. (The small print: a door is enclosed by the rooms on both sides; a backdrop is never enclosed.)

Enclosure is only useful when being used as a question. So the following is fine:

if the player encloses the fob watch, ...But these will produce problem messages:

The player encloses the fob watch. The location of the trilobite is the Museum.

‘Enclosed by’ includes things in containers players are carrying, like it says, which is useful. I had rules in my game that said the player can’t leave while ‘carrying’ a diamond ring due to a security system. Rovarsson broke the game by hiding the ring in a rucksack, since then it wasn’t ‘carried’ according to inform. Switching it to ‘enclosed by’ foiled his plan.

Example 39, Van Helsing, describes wayfinding, helping Dracula chase down the player:

Every turn:

if the location of Count Dracula is not the location of the player:

let the way be the best route from the location of Count Dracula to the location of the player, using doors;

try Count Dracula going the way;

otherwise:

say "'Muhahaha,' says Count Dracula."

Finally (Phew! I think I bit off more than I can chew), we have 3.26, Directions.

Directions are a ‘kind’, but not things or rooms. Every direction must have an opposite:

Turnwise is a direction. The opposite of turnwise is widdershins.

Widdershins is a direction. The opposite of widdershins is turnwise.

Hubwards is a direction. The opposite of hubwards is rimwards.

Rimwards is a direction. The opposite of rimwards is hubwards.

Ankh-Morpork is hubwards of Lancre and turnwise from Borogravia.

This will mess up the automatic Index map, since it doesn’t know how to draw it, but you can say:

Index map with turnwise mapped as east.

Example 40 is a way to change the directions or exits of a room.

Example 41 is way to change compass bearings to be based on hexagons to work with wargaming. It also includes a picture of a wargame! You can tell the author really likes wargames, as they go into the history a lot here. My dad loved these (he’s still alive, but I never see him play them).

Example 42 is nautical directions. I honestly love it when people who put port/starboard in leave them as E/W as well for convenience.

And that’s it! Whew!

You can do a ton in Inform with just the stuff in this chapter.