And as soon as I posted this, inspiration struck.

> search dishes

Glancing through the piles of dishes, you come across one with a (rather revolting) circular pattern of mould.

Ugh. I’m glad the need to SEARCH everything has generally faded with time. We can also LOOK UNDER the bench but only find “plate after plate of yellowish jelly and staphylococci”.

So let’s give this another shot!

>x mould

It seems to have been contaminated by a spore of mould, because a circular colony of mould has grown across the surface of the agar. Interestingly, near the edge of the mould, the bacteria seem to have gone, leaving only a faint ghost image.

Oh, so we don’t even need to infect the plate ourselves—just draw Fleming’s attention to it? That’s certainly a fairer puzzle, in that it doesn’t require you to know how penicillin was discovered in the first place!

But you still need to know to SEARCH BENCH and find the one dish, so…still not very fair if you don’t know that. Nelson’s games are (in)famous for expecting a certain level of erudition from their players, and while I can translate Latin quotes and know a bit about the history of medicine, I think I’m going to be horribly lost when the puzzles depend on knowing Proust.

Anyway, let’s put it on Fleming’s suitcase where he’ll have to notice it, and…

Fleming comes in again, and you hide once more. His eye is caught by the mouldy dish on top of his suitcase. Tutting with exasperation, he tosses it aside without looking at it, and is about to move the trunk when he thinks of something and wanders back out.

Oh.

Well, what if we…

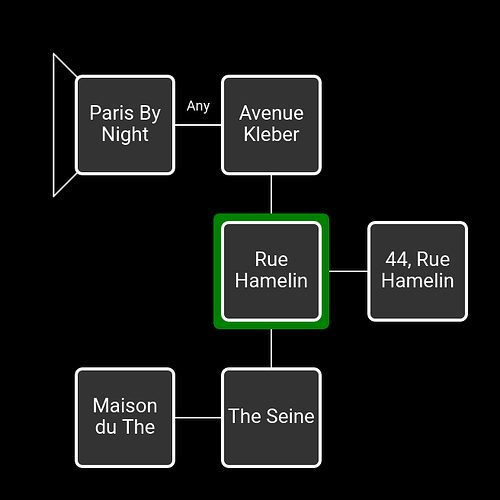

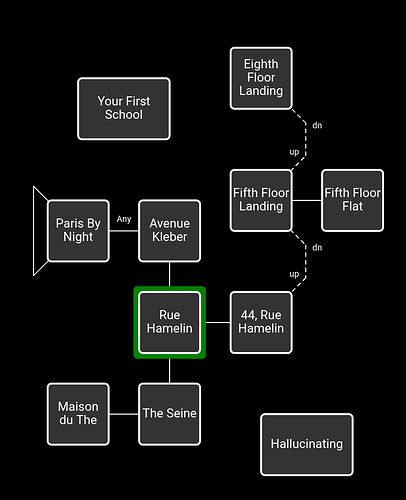

>push suitcase east

So now it’s in the staircase instead?

Fleming comes along, mildly surprised to find that he accidentally left his suitcase out on the landing. As he begins pushing the trunk into his laboratory, he can’t help noticing the mouldy dish on the top. “That’s funny,” he exclaims, forgetting the trunk and striding away with the dish to show a colleague.

[Your score has just gone up by one point.]

The now-famous quotation! In the words of Isaac Asimov, The most exciting phrase to hear in science, the one that heralds new discoveries, is not “Eureka” but “That’s funny…”

There’s no way I would have gotten that if I hadn’t been shoving the suitcase around in my previous unsuccessful explorations.

This is when the time-window opens, but we still have a puzzle piece to find! Since objects are scarce in this game, a bit of brute force looking for things to interact with reveals one single piece of scenery that’s implemented as its own object:

…On one wall is a framed certificate.

>x certificate

Mounted on a grey board, it certifies Alexander Fleming’s distinguished record as a surgeon in the Great War.

A grey board, you say?

>take certificate

You peel away the certificate, and the grey board it was mounted on falls to the floor. Another jigsaw piece!

Sometimes, brute force really is the answer!

We missed our opportunity to go to the Land, but we do still have the clock, so…

>set clock to 1

You shorten the time left on the clock.>z

Time passes.From inside the rucksack, the ormolu clock makes a rustle-click.

Oh right. We turned it off.

>turn on alarm

The latch on the clock is now on.>set clock to 1

You shorten the time left on the clock.

And now we get taken back to the monument. This piece goes at c3, and lights up with “a racing steam train”.

1 2 3 4

+----------------------------------------------------+

|............. ooooooooooooo|

a |. Mould Park o|

|......o...... oooooo oooooo|

|ooooooooooooo |

b |o Invalid |

|oooooo.oooooo . |

|.............oooooo oooooo............. |

c |. Glass .. Carriage oo Train .. |

|.............ooooooooooooo............. |

| . o . |

d | |

| |

+----------------------------------------------------+

So now we’ve got another option: Proust or train? I know a lot more about trains than I do about Proust, so my vote’s for that one, but we will have to face b1 eventually.

Before we go, also:

[ Footnote a1: ]

Sir Alexander Fleming deserves some of the credit for discovering penicillin: for untidiness, habitual good observation and enormous luck. A petri dish he left in the lab while on holiday in 1928 became contaminated by spores of penicillium, a mould common in most London gardens. (Fleming’s highly unreliable official biography claims - as he did - that this blew in through the windows, but actually it was due to sloppy conditions at St Mary’s.) The freak combination that year of a cold spell followed by warmth was the only possible way the mould could have killed the bacteria.

In fact, John Tyndall had noticed this property in 1875: but Fleming identified a chemical cause, and investigated. He collected moulds from everything and everyone he met for a while (even in the Chelsea Art Club, of which he was a keen member).

Fleming’s laboratory has been restored and is now open to the public.

Having made the medical breakthrough of the century, he lost interest. He decided it was unstable and useless, inexplicably missed the obvious experiments and largely forgot the matter. Not until 1940 did the brilliant work of Chain and Florey lead to medical triumph. The three men shared the 1945 Nobel Prize.

My understanding is that Fleming did experiment with penicillium for several years and present several papers on it, but wasn’t able to isolate enough penicillin to do specific chemical experiments on it until his collaboration with Chain and Florey. But then again, I’m not a historian.