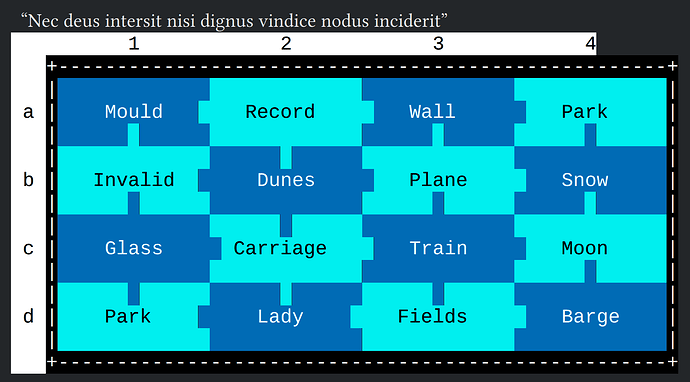

40% of the vote wants to go to D3, the fields of cabbages, so strap in and let’s check this out!

Chapter Eleven - Banburismus

Cabbage Fields

A brightly overcast day of clouds and light rain, the cabbage crops luridly green in the broad loam fields. On the horizon there’s nothing but some grey trucks some way to the north; nearer to hand, to east, is some sort of barn, guarded by rather bored soldiers in German army uniform.

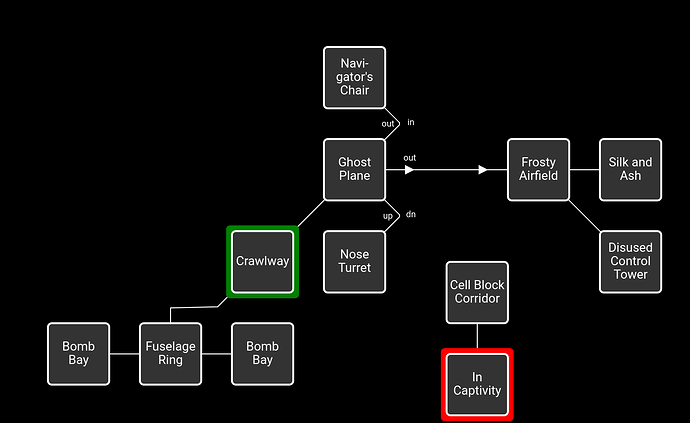

Uh oh! “Banburismus” is a term coined by Alan Turing, for a certain step in analyzing Enigma-encoded messages. And given that we’re in 1941, I suspect that’s what we’re about to be doing. (Though given that there are German soldiers here, not English ones, maybe we’re trying to leak information to the Allies?)

>n

You approach the grey trucks, almost bouncing on the springy loam. It’s a military convoy going nowhere in particular, but you’re captivated by the curiously beautiful but distant sound of the drivers sitting about under a tarpaulin tent, singing the “Wacht am Rhein”. And yet you drift backward again, and have gone nowhere.

“The Rhine-Watch”, a German anthem from the 1800s.

I’m not sure what’s going on with “drifting backward again”. But let’s go walk past those German soldiers with our British army uniform. They probably won’t recognize the difference.

>e

Inside the Barn

For a barn this is a solid building, with a tiled floor, spear-thick walls and a high, decently water-tight roof. Benches are covered with paper, black and white maps and boxes of electrical gear.

An exceedingly tall wardrobe reaches up almost to the ceiling.

Black, dressed in uniform, is sat at a bench in front of a weird typewriter.

A slip of paper, bearing the Wehrmacht stamp, has fallen from Black’s pocket.

Paper, you say?

>get paper

(the Wehrmacht paper)

Your presence here seems somehow too insubstantial for that.

This is another area of the game where I know a minor spoiler. For some reason, the rules of time travel have changed here, and we’re an invisible ghost, able to observe but not to interact. Our job here is to gather as much information as we can before we become substantial again.

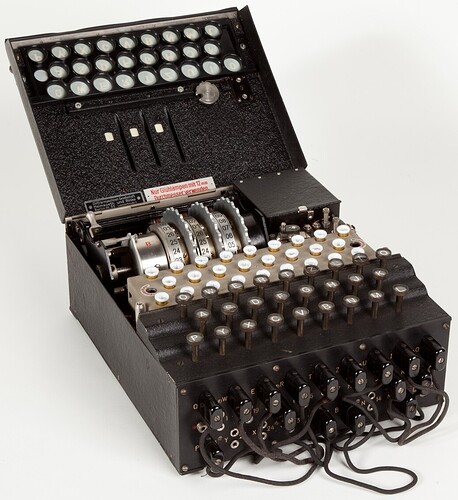

That “weird typewriter” is probably an Enigma machine:

This was one of the first big successes in electronic cryptography, and the machine that made cryptanalysis into a Big Deal for national security—the Allied efforts to crack it, and their eventual success, had a significant effect on the course of WWII. Alan Turing, one of the great luminaries of computer science (though it didn’t really exist as a field during his lifetime), was at the center of these efforts and is credited with saving countless lives by shortening the course of the war. (After the war, he was outed as gay, convicted of homosexual acts, and castrated; he committed suicide shortly thereafter. The British government apologized for this in 2013 and now his picture is on the ₤50 note. But as a result he’s even more famous in the queer community than in the general public.)

To use the Enigma machine, you’d insert three rotors of your choosing (the gears with numbers on them at the top of the machine), turn them to a position of your choosing, then type on the keyboard; every time you pressed a key, a different letter would light up on the panel above the keyboard, and the rotors would move to a new position. The system was designed to be symmetrical, so the same process was used for encoding and decoding.

Later versions also had the “steckerboard” on the front, where you could connect different sockets to scramble up the output even more. If you connected A to B, for example, then every A in the output would be replaced with a B, and vice versa. To decode a message, you would need to know which rotors were used, what positions they started in, and what steckers were being used. (For some reason they’re always called “steckers” instead of “plugs”, even though Stecker is just the German word for “plug”.)

Based on the title of the chapter, I think we’re going to be helping the Allies figure out whatever message Black is sending, by leaking some information to them. Though if Black wants to improve history, I’m not sure why they’re working with the Nazis. The actions of Nazi Germany are considered pretty universally and unequivocably bad.

>x wardrobe

The wardrobe’s very tall; there’s nothing underneath or behind it as far as you can see, and your ghostly self seems too insubstantial to get the door open.

Nothing underneath or behind, but what about on top? It’s time for the minor spoiler: this is an incredibly unfair puzzle that fans of Photopia might find very familiar.

>fly

Amazingly, your ghost can fly! You swoop around the room in childish delight, while Black doggedly works through some message below. Before you sink back to earth, you swipe at the wheels marked I and III (on top of the wardrobe), but of course your hand passes through them.

That’s the only part of this chapter I know the solution to, but I would never have gotten it on my own.

So, Black, what are you doing?

>x black

Black is dressed in a cypher clerk’s uniform, and looks keen. Although Black seems slightly more substantial to you than everything else, there’s still no sign of recognition.

>x machine

It bears the legend “Enigma”, but you can see almost nothing of it because Black is so intently hunched over the keys. There are three odd wires, the kind used for joining two terminals together, thrown to one side.

So it is an Enigma! And the kind with steckers!

>x paper

(the Wehrmacht paper)

In Black’s handwriting:

Stngs 11, 7, ?

[That third number is indecipherable, where the paper has been torn.]

a - g

w - c

v - t

u - j

y - r

[…At which point the tear cuts off the paper.]

Oh, and we have their notes, too! This should definitely be enough information for the Allies at Bletchley Park to do their magic.

>get paper

(the Wehrmacht paper)

Your presence here seems somehow too insubstantial for that.

No matter. We can make a copy of it once we’re substantial again.

The question is, how do we accomplish that?

Well, we do have a new verb:

>fly

Your ghostly spirit rises up and away, into the clouds, far, far across the fields and then the ocean! Night and day pass but still you fly, captivated. The mist gathers.

Then, with a thump, you bang your head against something.

Disc Room

This is a tiny tetrahedral annexe of a room, whose only clear feature is a broad black disc embedded in the floor.

And we’re back in the Monument. But something is different. If we look at the board, D3 is no longer fields of cabbages: it’s now a Victorian country house!

I’ll be honest, I have no idea why that segment just happened, or why the rules of time travel are different here. But it seems pretty clear that we need to go explore D3 again. This time we’re…

Hiding from Bletchley Park

Dusk on an overcast day of clouds and light rain, in which the Victorian awfulness of Bletchley Park country house seems especially dismal. It is surrounded by crude war-time huts all over the grounds, the nearest some way to the north.

You crouch in an old birdwatchers’ hide by the lake, while disconcertingly alert military police patrol up and down. The hide extends a little east.

Among some lead shot scattered over the mud is a spent cartridge.

[Your score has just gone up by one point.]

Okay! So we’re on the Allies’ side this time. Bletchley Park is where Turing and his ilk worked to decipher the Enigma messages, and presumably where we need to deliver our information. Hopefully they won’t question why we know these things. Or will accept “time travel” as a valid excuse.

>x shot

That’s not something you need to refer to in the course of this game.

>x cartridge

Fired from a shotgun, perhaps.

>get cartridge

Taken.

I have no idea what this will be useful for, but it’s portable, so we’re taking it.

>e

Sheltered

The hide is, indeed, sheltered from the elements, about two meters on a side and unbroken but for a slit window and the muddy climb out to the west.

An old flat cloth cap hangs on a nail.

Another portable thing! No description this time, but we can wear it. I’m sure it will complement our British Army officer’s uniform nicely.

Cap on head, let’s see if we can convincingly impersonate an officer:

>n

The MPs catch you at once, or as near as makes no difference.

Exposed

Two burly young men have you pinioned immobile, in the middle of the lawn halfway between the hide and the hut. A third, who has a corporal’s stripes, wants answers, and wants them quickly.

“All right, you,” begins the Corporal, and then suddenly notices your uniform and salutes. But then his trained eye latches on something. “Aren’t you a little young for Boer War campaign ribbons, sir?”

The Corporal’s patience having run out, you’re stripped of your belongings and marched off, past the Testery, past the Newmanry, down Wilton Drive to the nearest police cells. This is a civilised country, so see you in 1962.

*** You have been stranded in the past ***

Dammit. Who would have thought the soldiers at Bletchley Park would be good at catching impostors?

What if we try the Titanic uniform?

>n

The MPs catch you at once, or as near as makes no difference.

Exposed

Two burly young men have you pinioned immobile, in the middle of the lawn halfway between the hide and the hut. A third, who has a corporal’s stripes, wants answers, and wants them quickly.

“All right, you! Tell me just what you are.”

At least they don’t think we’re a spy. Now what should we claim to be?

>corporal, time traveller

“A likely story! Now come on, the truth.”

Uhh…

>corporal, spy

The rest, as they say, is silence.

*** You have been summarily shot ***

I love that there’s a custom response for that. In a game that’s as tightly-constrained on resources as this one, the little touches like this really shine.

Well, we were in a birdwatchers’ hide, and we have a shotgun shell. How about…

>corporal, hunter

“He might be, Corp,” a voice behind your left ear opines. “Careless talk,” the Corporal admonishes. “As for you… the Officer of the Watch comes on at midnight, and until then a little confinement is in order!”

You are escorted to the nearest hut and shoved inside: a guard is placed. “Get some kip, you’ll be needing it,” advises the Corporal as he slams and locks the door.

Hut 31

One of the impromptu huts disfiguring the grounds of Bletchley, this crudely heated asbestos and corrigated iron shelter offers little comfort. It has no very obvious function.

An intercept, a thin yellow strip of paper, is pinned up on the wall.

A heavy-looking crate occupies one corner, with a War Office seal across the top and very stern instructions upon it.

[Your score has just gone up by one point.]

Huh, this might be the first time the game has used a gendered pronoun for White. I wonder if that’s intentional. While the corporal is eagle-eyed enough to spot inconsistencies in our officer disguise, we are wearing a stolen uniform that’s too big for us, and it makes sense that he wouldn’t look as closely at a disguise he’s less intimately familiar with.

>x intercept

“hzsruuzstcrlumftbavtjifulzucnhsrivevvzffuzvoz”

“One for you to practice on when it arrives - remember the principle of Banburismus!” is pencilled below, and signed just “Newman”.

Oh lord. Are we going to need to decipher this ourself? “Newman” here would be Max Newman (né Neumann, renamed to sound less German), an English mathematician who created the first programmable electronic computer. He was the main force behind breaking the Lorenz cipher, a separate encoding machine used by German high command.

>x crate

“Danger! Do Not Open! Danger!” And a skull and crossbones.

Let’s open it!

>open crate

But that would break the seal.

It’s okay, we won’t be around long enough to deal with the consequences. (The RZ-ROV doesn’t work, unfortunately, since there’s nothing metal for the magnet to stick to.)

>break seal

You boldly and irrevocably break the seal, opening the crate.

Now what do we have here?

In the war office crate are an Enigma machine and wheels I, II, III, IV and V.

Yep, it looks like we’re about to do some codebreaking!

We may not actually need Banburismus, though, because we’ve stolen quite a bit of information from Black. What specifically do we know?

- Wheels I and III were on top of the wardrobe, and thus not in the machine. Black must have been using wheels II, IV, and V.

- The wheel settings were 11, 7, and something unknown, in that order.

- There were three steckers set off to the side, not being used.

- Five of the steckers are A=G, W=C, V=T, U=J, and Y=R.

What do we not know?

- The order of those three wheels: there are six possible orderings.

- The position of the third wheel.

- The remaining two steckers. (The machine has ten, and three were unused, so there are seven in use, and we know five of those.)

The steckers shouldn’t be much of an issue. If we don’t have them, there will be four letters swapped in our output, but it should still be legible enough to understand. The other pieces of missing information are more of an issue. Six orders × 26 positions for the last rotor gives us 156 possibilities; that wouldn’t be too hard for Bletchley Park to brute-force, but we’re just one person in a room with an Enigma machine. (Plus, this is a puzzle in a game.)

Maybe we will need Banburismus after all.

>take machine

With enormous effort, you manage to lift the machine up to a table.

Now let’s see what we can do with this.

>x machine

The Enigma cypher machine looks a little like a lap-top computer built with 1930s technology. There is a German-standard typewriter (QWERTZUIO…) keyboard, a lever switch, an array of little lamps (one for each letter) in the same pattern above, a steckerboard below and a square red button. Behind the lamp-board are three slots made to take special wheels. At present, the three wheel slots are empty.

The lever is switched on (in forward, encryption position).

>x steckerboard

The steckerboard is an array of wire terminals, one for each letter, arranged in a typewriter pattern. There are ten “stecker” wires which may connect together pairs of terminals. [You might try “stecker a to b” to make such a connection, “unstecker x” to unplug the wire connected to x, or just “unstecker” to tear the lot out.]

“x” is steckered to “e”

“f” is steckered to “g”

“y” is steckered to “j”

“o” is steckered to “n”

“m” is steckered to “r”

“c” is steckered to “a”

“i” is steckered to “z”

“l” is steckered to “s”

“u” is steckered to “v”

“b” is steckered to “d”

>x wheel i

This is one of the five wheels in the Enigma set, its ten cogs in sequence bearing the numbers 1 3 5 6 8 11 20 2 4 7.

>x wheel ii

This is one of the five wheels in the Enigma set, its ten cogs in sequence bearing the numbers 23 11 14 5 7 9 1 6 2 10.

>x wheel iii

This is one of the five wheels in the Enigma set, its ten cogs in sequence bearing the numbers 4 16 7 21 11 22 8 17 1 3.

>x wheel iv

This is one of the five wheels in the Enigma set, its ten cogs in sequence bearing the numbers 25 24 23 1 5 10 15 6 8 7.

>x wheel v

This is one of the five wheels in the Enigma set, its ten cogs in sequence bearing the numbers 6 18 5 4 21 23 14 2 8 17.

Ah! Okay, so the wheels have different numbers on them. This narrows down the possibilities for which is which. We know the first wheel must have an 11 on it, and the second wheel must have a 7 on it. II has both an 11 and a 7, IV has only a 7, and V has neither. Which means the wheels must come in the order II, IV, V.

The square red button is also implemented, but has no description. None of the other parts of the machine are interactible.

I think we’ve reduced our possibilities down to 10. I thought the wheels had 26 positions, but it looks like I was wrong about that—and 10 is a very feasible number to try by hand. I don’t think we can actually do Banburismus here, because that relies on multiple intercepts and their indicators (a mechanism the Germans used to encode the wheel settings), which we don’t have.

So let’s give this a try.

>get ii then put ii in machine

Taken.

You put wheel II (which is now at 23) into the Enigma machine.

>set ii to 11

You set wheel II (which is now at 11).

>get iv then put iv in machine

Taken.

You put wheel IV (which is now at 25) into the Enigma machine.

>set iv to 7

You set wheel IV (which is now at 7).

>get v then put v in machine

Taken.

You put wheel V (which is now at 6) into the Enigma machine.

>x v

This is one of the five wheels in the Enigma set, its ten cogs in sequence bearing the numbers 6 18 5 4 21 23 14 2 8 17.

Now for the steckers.

>unstecker

You unstecker all the terminals, and now have ten pairs of steckers free.

>stecker a to g

You stecker “a” to “g”.

>stecker w to c

You stecker “w” to “c”.

>stecker v to t

You stecker “v” to “t”.

>stecker u to j

You stecker “u” to “j”.

>stecker y to r

You stecker “y” to “r”.

And now…how do we type in the intercept?

>type hzsruuzstcrlumftbavtjifulzucnhsrivevvzffuzvoz

There’s nothing sensible to type into.

And also the Z-machine’s input opcodes can’t handle something that long.

>type h

You press “h”. Wheel II moves the letter eleven places back to “w”. Wheel IV moves the letter seven places back to “p”. Wheel V moves the letter six places back to “j”. Current runs back through the steckerboard, from “j” to “u”. Lamp “u” comes on.

Wheel II rotates to show 14.

[Your score has just gone up by one point.]

Okay! So this is really cool. We have a full simulation of the Enigma machine and its rotors. But this also means we have to type in each letter one at a time.

Let’s speed this up a bit.

>type h. type z. type s. type r. type u. type u. type z. type s. type t. type c.

[a lot of output]

Partway through this flood of messages:

[For more dramatic effects, you might try >type “message”]

Oh. Quote marks. Let’s try that. First, reset the wheel:

> set ii to 11

You set wheel II (which is now at 11).

Then:

>type “hzsruuzstcrlumftbavtjifulzucnhsrivevvzffuzvoz”

[To make this a little easier in future, you might like to “type intercept”.]

That’s even easier!

But as it turns out, we don’t need it, because here’s our first attempt:

You type “hzsruuzstcrlumftbavtjifulzucnhsrivevvzffuzvoz” at the Enigma machine, which works away producing “urgentadricanofdensivekmminentstoxadriapfstox”.

I didn’t think the Z-machine could actually handle this. I’m definitely impressed. And we got some excellent luck—the right wheel setting on our first try! No brute-forcing needed!

Breaking this into words, we’ve got URGENT ADRICAN OFDENSIVE KMMINENT STOX ADRIAPF STOX. The letter substitutions might come from the missing steckers, but in that case, we’d expect every F to become a D (and vice versa), and that’s not what we see. So Black might have just made a mistake. The Xs should probably be Ps, so that says STOP and ADRIAXF, but I have no idea what ADRIAXF is…

Wait. No. Look at the description from when we were pressing each letter one by one.

>type r

You press “r”. Current runs through the steckerboard, from “r” to “y”. Wheel II moves the letter seven places back to “r”. Wheel IV moves the letter seven places back to “k”. Wheel V moves the letter six places back to “e”. Lamp “e” comes on.

Wheel II rotates to show 9.

Current runs through the steckerboard for inputs and outputs! In other words, letters get steckerified when we type that letter, and when we output that letter! So let’s try steckering D to F, because of “Adrican” and “ofdensive”, and steckering X to P, because of the repeated word “stox”. If those aren’t right, we’ll try K to I, because of “kmminent”. And we’ll see if any of these make the last word make sense.

>stecker d to f

You stecker “d” to “f”.

>stecker x to p

You stecker “x” to “p”.

>set ii to 11

You set wheel II (which is now at 11).

>set iv to 7

You set wheel IV (which is now at 7).

>set v to 6

You set wheel V (which is now at 6).

>type intercept

You type “hzsruuzstcrlumftbavtjifulzucnhsrivevvzffuzvoz” at the Enigma machine, which works away producing “urgentafricanoffensiveimminentstopafriendstop”, which must surely be Black’s encoded message!

Just as you experience a moment of pure triumph, officers and boffins burst into the room, a crestfallen Corporal behind them. You’re seized at once, of course.

“My God,” says the leading boffin, “This spy has the secret of the machine! This compromises everything we keep hearing from ‘Agent Black’! Devilish cunning ploy.”

For you, though, such elevated debate is a thing of the past.

Inescapable Conclusion

The cell to end all cells, this one is remarkably bleak and secure. One can only pray for some supernatural escape.

[Your score has just gone up by one point.]

Oh! Okay!

So first things first. Black’s message was URGENT AFRICAN OFFENSIVE IMMINENT STOP A FRIEND STOP. Black was sending this information to…presumably the Germans, since they were using an Enigma. The fact that we deciphered it…proves that Black is a double agent? But why do they associate us with Black? And in 1941, surely they could crack this intercept on their own?

This part doesn’t really make sense to me. What do you all think? Any ideas on why our breaking this intercept saves history?

Second, we’re now in an inescapable cell. But we were just in another inescapable cell, and we know supernatural escape can come! We also have our full inventory, so we could just warp back with the clock, but the room description is giving us a strong hint—and I want to see the fully-completed Land.

>pray

Do you really deserve divine intervention, I wonder?

A fair question. But I think helping the Allies win WWII (or helping them win faster) is a much less ethically fraught action than assassinating Archduke Ferdinand and setting off WWI. That might have been a better time for moralizing.

The air here suddenly seems disturbed, and a kind of cloud gathers from light winds and currents.

From inside the rucksack, you hear a bell ring.

Ah, right on time!

>press device button

The cloud of disturbed air condenses into a kind of spherical ink-black ball, large enough to swallow you up whole.

And the ball can take us back to—

As suddenly as it enveloped you, the blackness begins to thaw and melt, like snow into an ash-grey slush which drifts and piles into landscape.

You have returned to the Land. Grim, monochrome steppes, wide and exposed beneath a brooding sky, the colour of boiled bruised potatoes. Bleak mountain crags surround a huge plain. The pyramid gleams gold like a beacon, like lamplight in the window of a farmhouse at night.

The Land, now complete, with all sixteen pieces in place! I’m making another save here as usual, and next session I’ll explore the areas that were shrouded by mist before. But first, I want to wrap up D3.

[ Footnote d3: ]

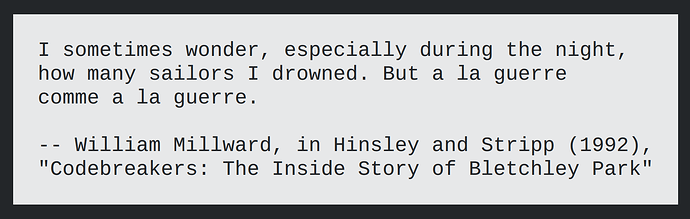

The Enigma (a modified commercial cypher machine) was considered absolutely unbreakable in Germany, but a team of mathematicians led by Newman and Turing found a laborious way to crack it, exploiting the fact that steckering is reciprocal (i.e. A goes to B means B goes to A). This technique was called Banburismus after Banbury, the town from which their supply of writing paper came.

Beyond paper, they used “bombes” - mechanical combination-checkers invented in Poland before its fall, and run by teams of girls sworn to secrecy who had no idea what they were doing - until finally Turing invented the computer: the valve-driven Colossus (which could execute a form of program with conditional branches).

Bletchley Park, halfway along the now-closed railway between Oxford and Cambridge, is no longer in use, and the huts (the Newmanry, after Newman, the Testery, after Major Tester, and so on) are demolished.

The real Enigma machine has a set of 8 wheels with 28 settings each, but the one in this game has the right idea.

The information found was an enormous (Churchill claimed, decisive) advantage to the Allied forces: from the Battle of Britain onward, essentially all German military communications were read, though less imaginative generals (notably Montgomery) often failed to act on these because they were too good to be true. (Amazingly, one of Rommel’s orders from Berlin actually reached Montgomery first.)

I mentioned above that Newman generally gets the credit for inventing the Colossus, but of course it was an enormous collective effort.

The puzzles in this chapter were definitely fun, and seeing a recognizable message come out of the Enigma was incredibly satisfying. But I’m still unsure what was actually going on here. Why were we a ghost? Why did the piece change its image? What was Black doing, and how exactly did we interfere with it?

Simulating an entire Enigma machine in Inform is still an impressive technological achievement, though, and I can forgive some narrative inconsistency for the sake of wedging this puzzle into the game.

18.txt (30.6 KB)

18.sav (7.5 KB)

land.sav (7.5 KB)

I’ve named this one simply “land.sav” since the Land is now complete. Next time we’ll explore it a bit more, and then decide where to go next!

(I also should really make a map for this area. I didn’t really think to, since everything is so disconnected spatially.)