ON “THE COMPLETE GUIDE TO KOHOLINT”

Of course the main impetus for the podcast was the fact that the overworld map of Link’s Awakening is really really good. The density and interconnectedness of the map, the “pacing” of interesting spaces being separated by just the right amount of boring space, is better than in any other 2D Zelda maybe. I’m pretty sure the original idea for the podcast was specifically to analyze the incredible construction of the overworld map as an overworld map, and we ended up talking about everything else in the game just because we happened to be on the subject.

The presentation of the map in “tiles” suggested the format of analyzing each screen individually, the way some podcasts will analyze a film one minute at a time. This seems like a bad idea on its face, because there’s 256 map tiles and a huge percentage of them are boring. But “a ‘terrible idea’ is just a fantastic idea you haven’t committed to yet,” and this problem presented the opportunity to do a daily podcast! A daily podcast where most of the episodes are only a few minutes long. Because most of the time there’s not much to say. But how fun, to do a daily podcast for 256 days!

We divided the series into 16 “sections” or “seasons” of 16 tiles/episodes each. We assigned one “important tile” to each season. For half of them, these were the tiles containing the eight main dungeons; for the others they were the locations of plot points breaking up the dungeons, like the ghost’s grave. These sixteen critical-path tiles were sure to appear in order.

Then I randomly divided the other 240 tiles among the 16 seasons, then I randomized the order of the 16 episodes in each season. Except we wanted the place on the beach where you get the sword to be for sure the first episode, and we wanted the Egg to be for sure the last episode.

So it was almost entirely random.

ON “RYAN VEEDER’S MUD WARRIORS”

(It amuses me to distinguish my Inform 7 game, “Mud Warriors,” from the Game Boy Studio adaptation, “Ryan Veeder’s Mud Warriors.”)

I composed all the music! There’s a download link at that itch page and there’s a YouTube playlist here. Both include all the “high-res” tracks I composed in GarageBand before the project got switched to Game Boy Studio. (Lance’s original pitch was to do one-bit graphics in RPG Maker.)

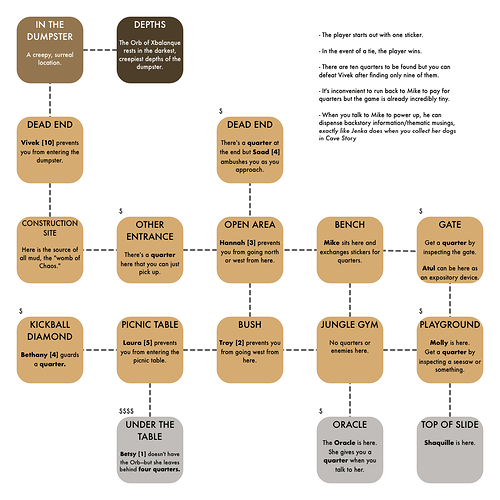

Other than that, my involvement in the project consisted mostly of high-level, hands-off stuff. I didn’t program a single thing. I didn’t write anything (except the pre-title opening text); all the additional writing is Lance’s. But I believe I was the one who suggested the combat system, which I stole from For the Frog the Bell Tolls (which is closely related to Link’s Awakening, how about that), and I sort of halfway redesigned the map in such a way as to make the gating work. Actually, I have the image I used to propose that map… right here!

Big spoilers!!!

ON WHETHER I KNOW OF BITSY AND MY TAKE ON THAT CONTROVERSIAL TOPIC

I only know a little bit about Bitsy. But I am deeply grateful to you for providing an opportunity to present my thoughts on this controversial topic in a context where nobody will start any sort of debate with me. Thank you. There are, after all, many other questions for me to answer, on many other subjects.

The usefulness of defining a category like “interactive fiction” is in carving out a universe of discourse where we can usefully compare similar entities. It is not useful to attach a value judgment to such a definition—like how some people insist that art has to meet some standard of quality to be considered “art.” This type of definition precludes a bunch of useful and interesting conversations distinguishing good art from bad art.

So I don’t believe there’s any privilege or status involved in classifying something inside or outside the category of interactive fiction. It’s just a matter of whether you get anything out of comparing it to other things in that category.

I think what unites the format of interactive fiction, what makes it interesting to compare Aisle to The Cave of Time in a way that neither can be compared to Super Mario 3D World, is that it relies on a verbal presentation. You can compare how works of IF use words to build environments and puzzles and experiences. The craft of IF is the craft of making words be interactive.

Obviously almost all games use words to different degrees. I don’t think there’s a hard line along this spectrum that delineates the universe of interactive fiction. It is useful for this sort of definition to be fuzzy. But I propose this “test” for gauging the extent to which it is useful to include a game in the category of interactive fiction: What would happen if you changed the language of the game to one you don’t understand? Or what if you censored all the text in that game?

Animal Crossing, for instance, has oodles of text. Playing it with no text would be an extremely impoverished experience—but you could still catch fish, change your outfit, buy furniture, decorate your house. You could even enjoy chatting with your villagers, if only via their body language. (I played Animal Crossing in French for a long time and didn’t understand a lot of it.) On the other hand, if you censored all the text in my wonderful game The Little Match Girl, you would not enjoy yourself nearly as much.

It seems to me that Bitly can be used to create games that rely so heavily on text as to be obviously and usefully included in the category of interactive fiction, and it can also be used to create games where the presentation and interaction are so text-independent that it would not make sense to call them interactive fiction, and it can be used to make games that stand between these extremes, such that the question of their classification would be very interesting to one who takes an interest in such questions. And that would be an incredibly useless sentence, were it not preceded by so many paragraphs of such excellent substance.

ON HANS CHRISTIAN ANDERSEN

In writing the Little Match Girl games I’ve slowly learned more about Hans and his work. He strikes me as a very sweet individual, and surprisingly weird or funny or subversive in a way that’s difficult to parse from all the way over here. I like him.

The games go off in all kinds of ridiculous directions, but I try to use Andersen’s stories as jumping-off points. The Little Match Girl 2 is distantly inspired by The Story of the Year, and The Little Match Girl 3 is “inspired by” The Snow Queen in perhaps the stupidest sense of the phrase.

I would like to think that, instead of or on top of being flights of my own personal fancy, the games represent my take on his worldview to some extent. But who knows.